On a recent Tuesday at the Trinity Community Commons’ weekly meal in East Nashville, a woman named Angie Duncan sliced a donated loaf of sourdough for dinner. She wore a beanie glowing with tiny Christmas lights. “I won that hat at bingo,” her husband Jimmy said. He’d played the game across town at Room In The Inn, a longtime resource center and shelter for Nashville’s unhoused community. It’s where the pair met before their wedding this year, which also took place at Room In The Inn.

Meanwhile, pans of pasta carbonara and salad were carried in, scratch-made at The Nashville Food Project kitchens with donated ingredients from local farmers and butchers. A neighbor named Peggy Frank sliced her homemade sweet potato pies. She brings a couple of them every week. Another couple brought a casserole dish of grits. At the end of the table, Meshach Adams poured glasses of tea. Home for the holidays from grad school at Alabama A&M, where he studies urban planning, Adams had been a regular at this meal for about two years before heading off to grad school. He learned about it while working on a pedestrian safety plan along Dickerson Pike with nonprofit organization Walk Bike Nashville and returned to see friends at what was once part of the rhythm of his life.

“Tuesday, 4:30 p.m? Come here,” Adams says of his routine. “This is a microcosm of what the world should be like.”

This microcosm includes an eclectic mix of neighbors, and blurred lines between helpers and those in need, between “volunteers” and “recipients,” where differing groups don’t stand on opposite sides of a table. Here, everyone serves and receives, and everyone sits to eat together, regularly, for a local bounty in the company of community.

“The most important part is you meet your neighbors,” says Zach Lykins, executive director at Trinity Community Commons. The food is a big draw, yes, but it’s also a community resource exchange that happens only from people knowing one another in a consistent way.

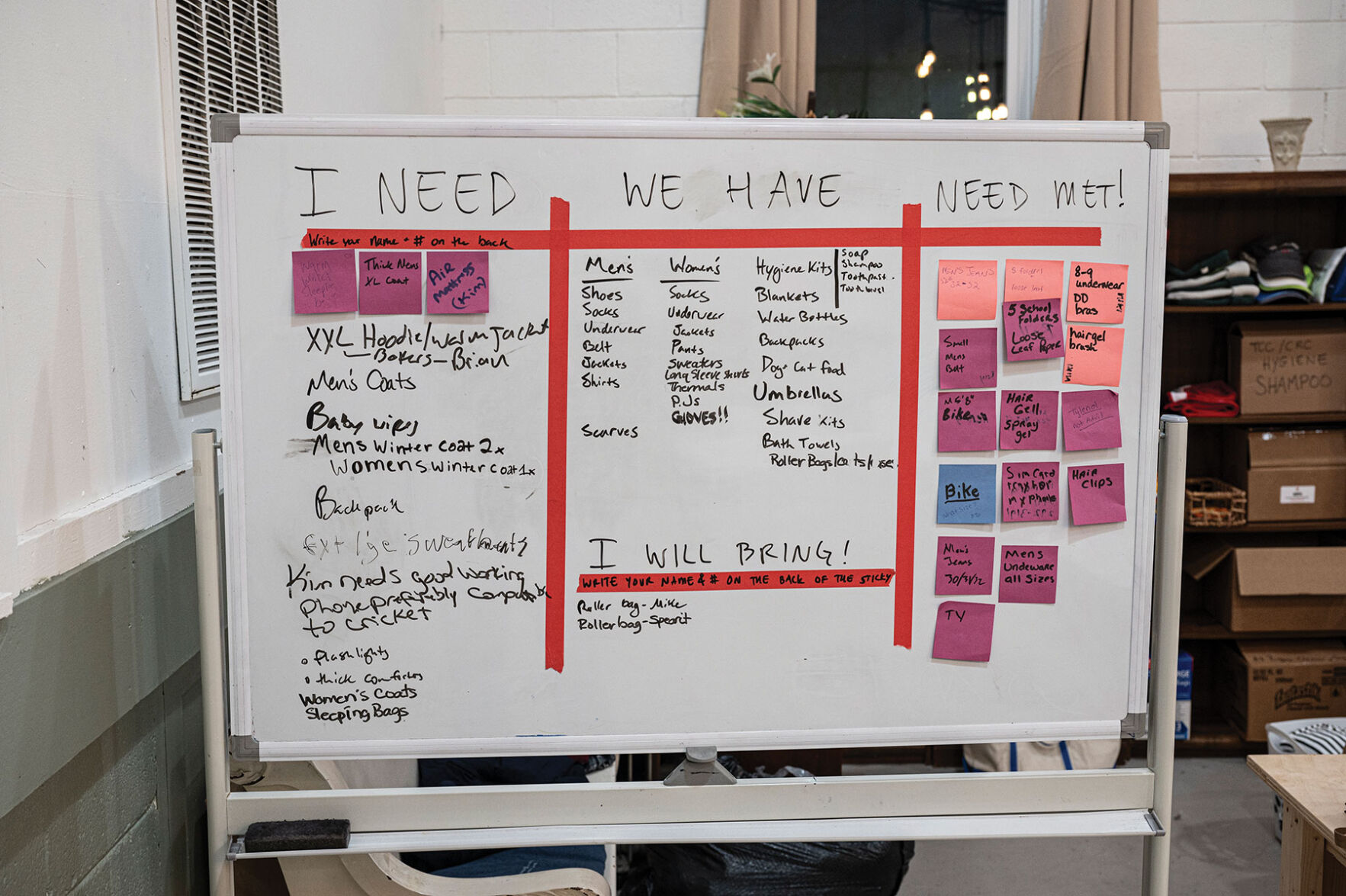

“If you have a resource to share or a need, come talk to me,” Lykins tells the group. He lives in Cleveland Park and initially came to the meal as a guest with a friend. Now he keeps track of needs on a whiteboard at the back of the room.

The dinner at Trinity Community Commons is not new. It’s been happening for more than a decade. But could it be a model for similar dinners around town in the future? Some local — and national — groups have taken an interest in community meals of late.

Food — its cost, its scarcity for some — has been on the minds of many. On the national stage, folks debated the price of eggs. “I won on groceries — very simple word, groceries,” President-Elect Donald Trump told Meet the Press recently. And yet economists say Trump’s tariffs could drive up the price of goods. Groups like the Tennessee Justice Center are bracing for potential increases in food insecurity by hosting webinars about significant cuts to the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and other benefits.

All this could make dinners like the one at Trinity more essential — not just in the sharing of food, but also in the sharing of community care amid what Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy last year described as an “epidemic of loneliness and isolation.” (Murthy’s office recently hosted a potluck to encourage community and released a handbook for hosts called Recipes for Connection.) In Nashville, the notions of knowing and better understanding one’s neighbors and strengthening the fabric of community have bubbled up during a bitterly divided election season when some have felt a desire to find hyper-local connection.

For example, Imagine Nashville, a 14-month community engagement project with input from 10,000 locals, included recommendations to foster belonging and community-building within neighborhoods. Black Mental Health Village might host more community dinners on the heels of its Friendsgiving. FeedBack Nashville, a community initiative to imagine a more just and sustainable food future, identified — based on hundreds of interviews and surveys — strengthening social fabric and diverse “third spaces” as one of its six pathways. The Metro Human Relations Commission will launch dinners called No Hate on My Plate in 2025.

“When we’re in community, we’re less isolated,” said the Rev. Kate Fields of St. Augustine’s Episcopal Chapel in an announcement about No Hate on My Plate at the Tennessee Local Food Summit in early December. “We trust each other more. We start to see each other instead of see past each other. I think that we become resilient in our differences. … People eating and laughing and talking and building relationships — this is the kind of world I want to live in. I’m convinced the table is that avenue.”

Participants at a workshop for FeedBack Nashville convened Sunday to discuss next steps in its six pathways. The workshop drew about 30 people from various fields (education, housing, transportation, food) who split into smaller groups, each focusing on one pathway. A group digging into the topic of community meals included Lykins, a couple employees and a board member from The Nashville Food Project, as well as Kamilah Sanders from Greater Than Equal, a state IT employee named Shalini Gupta, and Carson Bolding from B Corp, a company that measures social impact.

“If something like that had existed when I first moved here,” Bolding said, “I think I would’ve felt a lot more connected to my community, safer walking around my neighborhood, and more at home.”

The group discussed what more community meals could look like. Regularly occurring outdoor pop-ups on city streets with tents and tables for greater visibility? A tool kit for neighborhood associations on street-permitting and gathering resources for dinners? Identifying designated meal leaders with deep and varied connections within each neighborhood?

Could these meals — the group wondered — become an identifying and regular part of life, like the choice of church or club or gym?

“Wouldn’t it be cool,” asked Marcie Smeck Bryant, a board member at The Nashville Food Project and a regular participant at Trinity, “if people were saying, ‘What community meal do you go to?’”

Disclosure: Jennifer Justus previously worked for The Nashville Food Project. She left the organization in 2021.