Bars along Lower Broadway

When a woman walks up to a bartender and orders an “angel shot,” the bartender knows it isn’t because she wants a drink. Angel shot is code — a way for someone who feels unsafe to ask for help. The bartender can then help the customer to a taxi or otherwise separate her from whomever is a potential threat, be it a Tinder date, a longtime partner or a stranger in the corner.

In recent years bars, restaurants, music venues and even large event spaces like Nashville’s Bridgestone Arena have occasionally added signage to bathrooms, letting people know about the angel shot. That’s just one way businesses are working to reduce the incidence of sexual assault. Since 2017 the Sexual Assault Center has run the Nashville Safe Bar program to train hospitality workers to recognize and prevent sexual violence. New funding and a pandemic pivot are expanding the efforts this year, says Rachel Freeman, president and CEO of SAC. (Disclosure: Freeman is the daughter-in-law of Bill Freeman, owner of the Scene. He was not involved in the reporting or writing of this article.) In addition to Safe Bar, SAC operates several programs, including a SAFE clinic in Metro Center, where victims of sexual assault can receive a medical exam.

The idea behind these programs is to train hospitality workers to pay attention to worrisome behavior, from aggressive comments to overt attacks that can lead to sexual assault, sex trafficking and rape.

Window cling indicating that staff has been through Safe Bar training

Sharon Travis, outreach and advocacy specialist at SAC, was moved by a conversation with a man whose fiancée was sexually assaulted when in town for a bachelorette party. He called SAC looking for resources for her. “If this is a thing in Nashville, what kind of public health response can we provide?” Travis wondered.

SAC launched Safe Bar, modeled after a program in Washington, D.C., called Collective Action for Safe Spaces. In retrospect, Travis says SAC did things backward, starting the program first and then looking for funding. They offered a few trainings, including at Bar Louie in the Gulch, and with Play Dance Bar and others on Church Street. The program was adapted for Nashville’s entertainment culture and has expanded with assistance from the Tennessee Department of Health and the Tennessee Coalition to End Domestic and Sexual Violence. Other Tennessee cities with similar programs include Memphis, Chattanooga and Johnson City.

SAC is launching new trainings this April, timed with Sexual Assault Awareness Month. Travis’ goal is to see 100 Nashville bars trained by the end of 2021.

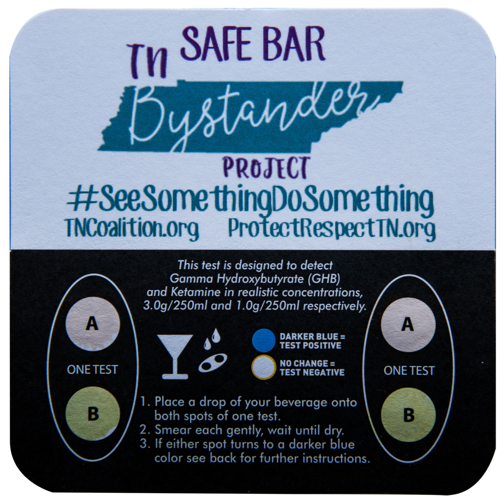

Such training is free for bars and includes collateral materials such as signage about the angel shot, coasters that change color to reveal the presence of date-rape drugs and window clings to show the public that staff has been through the training. Freeman and Travis hope that over time that decal will come to signal a place where locals and tourists know the bartenders and servers have their backs.

The SAC Safe Bar training includes several tiers, including a six-hour train-the-trainer program in which staffers learn techniques to then pass on to their co-workers. There’s a three-hour program for bar ambassadors who keep everyone updated on new developments and a 20- to 30-minute course that can be useful for bringing new staff up to speed and offering a refresher for previously trained employees.

Travis likes to see multiple bars do the training together as a collective. When Church Street bars finished the 2017 pilot, they then celebrated with an employee pub crawl to all the participating bars. The hope is that training and the window cling exert positive peer pressure. If 80 percent of bars on a block have the decal, what does it say about the 20 percent that don’t?

“It is naive to hope that all bars would want to do it,” Freeman concedes. But she does think that as Nashville boasts its tourist-centric “It City” moniker, Nashville may be able to also be thought of as “Safe City” — a place people can honky-tonk and drink beer without having to watch their backs, and a place where locals and hospitality workers alike can feel safe.

Super Bowl weekend is typically a time when reported sexual assault, sex trafficking and domestic violence rates rise. Any weekend with large crowds and widespread alcohol consumption can experience such upticks. Freeman says that when Nashville hosted the NFL Draft in 2019, SAC had triple the number of reported sexual assault cases than it does on a typical weekend.

The national statistics show that more than 50 percent of sexual assaults include one or more parties drinking alcohol, Freeman adds. But it must be underscored that consuming alcohol does not cause sexual assault. “We know there is a connection,” she says, “but it does not happen unless a predator or rapist is present.”

Freeman adds that “assault happens everywhere.” While there may be a preconceived notion that this is an issue for downtown bars, and that only women are at risk of being victimized, in truth, nowhere — and no one — is immune: college bars, neighborhood hangouts, music venues and event spaces.

Safe Bar coaster, which tests for the presence of date-rape drugs

Johnathan Jones, director of operations at East Nashville event space Studio 615, took his staff through the Safe Bar program and encourages their vendors to do the same. The process, he says, enables his staff to have open conversations about a topic that is often taboo. He has been pleasantly surprised about his employees’ awareness of signs of unsafe interactions. “It is not just a weird-looking guy with a hoodie who drops something into a drink,” says Jones. “Everyone has been really receptive to this knowledge. It helps us keep a trustable space, a safe space.”

Ellen Talbot is the lead bartender at Fable Lounge, and she agrees. “When we talk about it in Fable, I have never heard anyone say, ‘We don’t need this,’ ” she says. Talbot went through a similar bystander training program — Green Dot in Portland, Ore. While the specifics are different from Nashville’s Safe Bar training, the basics are the same. The idea is to let customers — those who may be in uncomfortable situations as well as predators — know that someone is paying attention.

“We bartenders are nosy, and we hear everything,” Talbot says. In one case, for example, a young woman was uncomfortable with the men at the table next to her. She couldn’t tell her server without being overheard, so she typed it on her phone, and showed the screen to the server, who then moved her to a different table. Other examples of avoiding direct confrontation — which may escalate a situation — are through distraction. Something as simple as spilling a drink may allow someone time to walk away and get in a Lyft.

“Sometimes, too, I might assume something is going weird, and when I ask, everything is fine,” Talbot says. “But it is better to check in than to ignore something dangerous.” What you want to avoid, she says, is “pluralistic ignorance” — the concept in which lots of people notice something wrong, but no one acts, assuming everyone else is OK with it.

Eron Johnsey, now the front-of-house manager at Game Terminal, went through the Safe Bar program when he worked at Mercy Lounge. Now he and Shane Batchelor, operations manager at Game Terminal, are working to train staff at their new pinball bar. “We have to have these conversations,” Batchelor says. “We want our guests to feel that they are somewhere safe and comfortable and fun 100 percent of the time.”

Sinema, a restaurant and bar known for its Bottomless Brunch, is a destination for groups looking for a good time, as well as for folks on a first date looking for a more intimate setting. Carly Houison, Sinema’s general manager, believes sexual assault is a citywide issue that needs to be addressed, and that hospitality workers are qualified to help.

“There is this giant drinking culture here,” Houison says. “This is a destination centered around drinking. My bartenders are incredible at hearing seven conversations at once. The servers are looking out for sections other than their own.” She says that, in the past, Sinema staff has helped get inebriated guests away from friends who didn’t appear to be looking out for them, or helped them get home in a Lyft. The Eighth Avenue restaurant and bar has a good relationship with Berry Hill police, and Houison says they respond quickly when the bar needs help. Houison has done much of this training on her own, and now plans to enroll in the Safe Bar program.