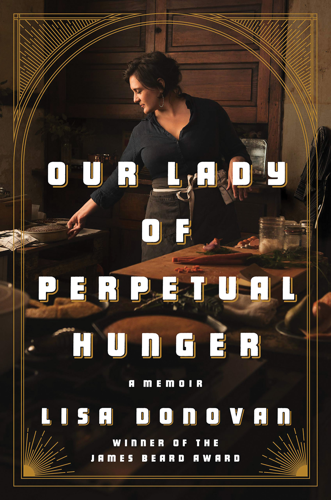

Lisa Donovan

“Stop letting men tell your story.”

After eating her cajeta ice cream and apricot dessert at an event, Mexican cooking expert Diana Kennedy said those words to pastry chef Lisa Donovan. That admonishment resonated with Donovan, who then embarked on a multiyear examination of her culinary career and her life experiences both in and out of the kitchen.

The result of that introspection is Our Lady of Perpetual Hunger, Donovan’s intensely personal but also universal new memoir, out Tuesday, Aug. 4, via Penguin Press. While Donovan has been working on her first book for years, it includes a lot of themes that many of us are grappling with in this complicated, quarantined 2020 — looking at our beliefs and the power structures around us, and trying to figure out what we’ve misunderstood and where we can be of use.

“I am a woman of a certain generation, and I was raised and told you can do anything if you just work hard enough — if you showed up and worked hard enough,” Donovan tells the Scene. But in professional kitchens, she increasingly felt like her hard work was not enough. Donovan’s skill with dough wasn’t enough to combat what she found to be pervasive barriers to advancement or even a decent income.

“Why did I think for so long that I could subvert the system?” she says.

Donovan underscores that she doesn’t want to come off as a victim — and she doesn’t — while still pointing out gender inequities in kitchens across the city and the country. “Women don’t get to show up and do the work the way men do,” Donovan says.

Donovan worked at Husk Nashville under Sean Brock and at City House under Tandy Wilson, after getting her start at Margot Café and Bar thanks to Margot McCormack. She was also the chef and owner of Buttermilk Road, a series of insidery and well-regarded pop-up suppers from 2009-2012 wherein diners were encouraged to show up solo and engage with people they didn’t know over the dinner table.

The book has been highly anticipated in food circles. In 2018, Donovan won a James Beard Award for an essay in Food & Wine magazine, “Dear Women: Own Your Stories,” which in rapid-fire succession mentioned her own sexual assault and abortion, as well as harassment and inequity in restaurant kitchens. The tone of that essay is reflective of Our Lady of Perpetual Hunger.

Throughout her decades finding herself as a daughter, wife, mother, friend, chef and writer, Donovan was inspired by many Nashvillians of stature at various junctures, including McCormack, Brock, Wilson and Alice Randall. She repeatedly thanks and praises her mentors and friends for inspiring her and supporting her. Seeing the people and places of Music City throughout the book, which travels across borders and through Donovan’s life, from childhood to the present, could make Nashvillians feel some ownership and connection to these personal stories.

Donovan is known for pastries that fuse time-honored Southern recipes like hand pies and “church cakes” with French baking techniques. She uses both sweet and savory ingredients, and has an appreciation for local produce and a willingness to be open to the traditions of others. Her story of learning to appreciate those aforementioned apricots — a fruit that tastes great in California, but not always in the South — is the quintessential Donovan telling. It’s revealing in the way in which she learns something new, funny and foul-mouthed, and connected to both food and people.

The book is a memoir and does not include recipes. It skewers not only the gender inequities in hospitality culture, but corporate ownership of restaurants, which she feels allocates money in all the wrong places:

When you have wealthy partners who are somehow willing to spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on light fixtures, or handmade linen napkins from their best friend in Charleston, and truly, horrendously bad art before they even open their doors, but cannot see their way to paying their cooks a living wage or establishing health-care benefits for them or supporting them as human beings rather than merely as a means of profit, you take an already complicated and outdated caste system of workers and destroy the fibers that keep them tethered to their already complicated work.

Some of Donovan’s motivation to re-examine her experiences and her beliefs came after getting a piece of advice: “The trick was a simple one: undo your miseducation.” That’s a line Donovan attributes to Randall, the award-winning writer and writer-in-residence at Vanderbilt University, who has been teaching that topic for years. (The phrase is a nod to the album The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill.) It’s another theme for 2020, as we all try to better understand topics on which we were misinformed. Donovan is appreciative of how Randall used her legendary cookbook library (thousands of tomes) to show Donovan the roots of the Southern recipes she loves: It wasn’t white women who were hostesses who created them; it was the Black women who worked for them. “My indignation came only because I was ignorant,” she writes. “This was obvious information. How did I need to be shown this?” Donovan also explores her own background, including that of her mother’s Mexican roots and the ways in which Mexican traditions were present and absent from her upbringing.

Donovan is as talented a writer as she is a baker. Certain phrases are to be set aside and savored like one of her City House cookies:

The lowboys creak and buzz, keeping all the leftover mise en place cool in the quart containers with their perfectly cut blue tape labels on their collars, looking like little schoolboys standing at attention with their perfectly pressed lapels.

While the book catalogs Donovan’s successes and frustrations, her emotional and intellectual awakenings, it is also a love letter. First to John, her husband and the sculptor behind Tenure Ceramics, which makes place settings for several restaurants in town. Donovan recounts their vision for their careers and their family before they were married, decades ago, and then demonstrates how they achieved that vision despite financial and other hurdles.

It is also a love letter to her children, and Donovan cites her daughter Maggie as one of her motivations for speaking out about institutions that don’t honor the accomplishments of women.

Finally, the book is a love letter to Nashville. Donovan moved frequently as a child, and growing up in a military family, growing roots and feeling connected to a geographic place has been powerful for her.

“This is where my family has lived for almost 20 years,” she says. “I raised my kids here. So many things about Nashville are unlike anywhere else in the world, how interconnected we all are. The way this city turns toward each other in real times of crisis is really second to none. The community in this city will almost break your heart it is so good. I will always have wanderlust, and I will always be a traveler, but Nashville is home.”

Parnassus Books is hosting a remote conversation for the book launch through a Facebook Live event with Donovan and songwriter Allison Moorer on Tuesday, Aug. 4, at 6 p.m. Signed copies of the book are available at Parnassus and The Bookshop, both of which offer contactless pickup.