Vodka Yonic features a rotating cast of women, nonbinary and gender-diverse writers from around the world sharing stories that are alternately humorous, sobering, intellectual, erotic, religious or painfully personal. You never know what you’ll find in this column, but we hope this potent mix of stories encourages conversation.

I know people who get emotional when discussing the burning of the Library of Alexandria. This says a lot about the company I keep (recovering high school Latin students), and even more about humankind’s infinite capacity for grief. That library has been gone for thousands of years, and yet it’s still being mourned with heartbreaking ferocity. To many, its name is synonymous with loss.

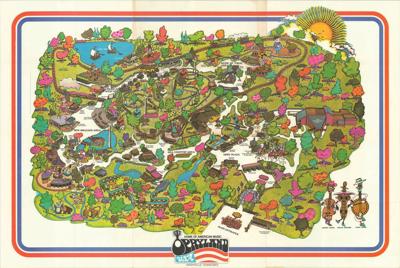

My Library of Alexandria is Opryland USA.

Nashville was home to an iconic theme park like no other in the country. Then it was shuttered for ‘no compelling reason.’

For those too young to remember the Clinton administration, Opryland was once Nashville’s very own amusement park, originally opened in 1972. Its rides, shows and concert venues were visited by millions of guests and countless music legends, making the park a beloved Nashville institution. But one day the “Powers That Be” wanted to build a mall, and that beloved Nashville institution was in the way.

So the park was closed in December 1997, when I was 7 years old. Opryland was systematically destroyed, piece by piece, until all that remained was the sad dry riverbed that was once the Grizzly River Rampage. By the end of 2011, even that unintentional memorial was gone.

I find there’s something particularly disorienting about losing a place. On some level we know every living creature will eventually die — every pet, every person, every animal we’ve parasocially bonded with via Instagram. That certainty doesn’t stop those losses from hurting, but it does take some of the burden off of us. We understand that no living thing, no matter how well-loved, can live forever.

But a place, theoretically, can. On July 17, 2025, Disneyland will celebrate its 70th birthday, while Walt Disney himself only made it to 65. Denmark has an amusement park that’s more than 400 years old. All over the world there are churches, temples, houses, schools and restaurants that will likely outlive any one of us. So when a place dies — not due to natural disaster but rather the whims of a multimillion-dollar entertainment/hospitality juggernaut — it forces us to wonder: Could we have saved it? The answer is almost always no (unless you are on the board of a multimillion-dollar entertainment/hospitality juggernaut).

I will take every chance I can to discover more of this endlessly evolving city

Because if love alone could save a place, Opryland would have been saved. It was loved as much as any place ever has been. Just go to the comments of any YouTube video, stitched together from hundreds of home movies, and you will see people still angry, still mourning, still wishing they could share this place with their own kids. By most accounts, Opryland was a profitable park right up until the end. Its closure wasn’t a death; it was an execution. If that sounds too dramatic, you’re underestimating how strongly its loss is still felt in our city. I would give my right kidney to ride Chaos tomorrow, and plenty of other Nashvillians feel the same. We could probably take up a whole kidney collection.

One day Opry Mills will also likely find itself on the wrong end of someone’s cost-benefit analysis. It too could become someone’s lost Library of Alexandria. My own childhood mall has already been flattened into a parking lot, along with my high school and my hometown movie theater. The universe I grew up in is shrinking every day, and all I can do is watch it happen. But still, if I could bring just one of my lost places back, it would be the one with the bumper cars. You would think I’d be more emotional about the loss of my school than the demise of the Rock n’ Roller Coaster, but I’m not. That’s partially because the school really did need to come down (it was allegedly riddled with asbestos), but also because I still have all the memories I made there.

The truth is, I don’t actually remember Opryland.

I know I went multiple times as a child. I’ve seen the photographic evidence. I remember other childhood trips, from even earlier ages: Disney World, Gatlinburg, SeaWorld. I even remember that weird Cabbage Patch hospital in Georgia I visited when I was 3. And yet I don’t have any memories of Opryland. No matter how much I sift through the ashes, not a single spark remains. It’s become a place I lost twice; once from the world, and again from my memory.

How cicadas reflect my queer experience

That’s just how it is sometimes. A loss can be loud, entering your life with wrecking balls and dynamite. But other times it’s quiet, like a snowflake melting on your skin. A part of my story melted away, and I didn’t even notice. Even if they rebuild Opryland tomorrow, I can never get those memories back. (But for the record, I would still really, really like them to rebuild Opryland tomorrow. The kidney offer still stands.)

There is no moral at the end of this story, no call to action. I could ask you to protect the places and memories you love, but I know that won’t always be possible. Maybe your library will never burn, but probably it will. That’s just part of life’s roller coaster. All we can do is enjoy the ride while it lasts.