In 2008, Omari Booker was arrested for a nonviolent drug offense. In a poetic gesture of optimism, he took an art class at Tennessee State University when he was out on bond awaiting sentencing. He entered Charles Bass Correctional Complex in 2009 with a 15-year sentence. Booker served three-and-a-half years before being released on parole. Fifteen — his moving solo exhibition at Elephant Gallery, on view through May 20 — marks the end of his parole.

In a June 2017 interview for Nashville Arts Magazine, Booker told me that when he was incarcerated, art became a way to feel free. “When I was drawing and sketching and listening to my headphones, I didn’t feel like I was in prison anymore,” he said. He wants his work to help others access freedom as well — from prisons socially or personally constructed; in other words, from whatever keeps us from liberation of the mind.

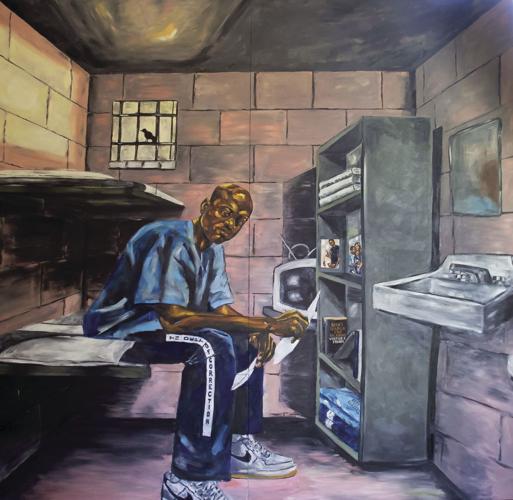

The two most prominent works in the exhibition are impressive self-portraits. “This Black Bird” is 96 by 96 inches — square like a box — and you really need the space of the whole gallery to take it in. In the portrait, Booker sits on the bunk in his cell, stooped over with a letter and an envelope in his hands. He’s looking down and to the side, like he’s paused his reading, or is preparing to read it again. His face is closed, troubled, and he is alone.

Another self-portrait called “Corrected” — measuring 60 by 48 inches — is hung directly across from “This Black Bird.” In it, Booker sits in a large armchair. He is barefoot, at ease. His long fingers hold a paintbrush. The window behind him is open, and he’s flanked by an easel and a record player. His expression is relaxed and open. Red and yellow flowers cascade around him. “This Black Bird” and “Corrected” show the artist at vastly different points, yet these works aren’t juxtaposed — they’re in conversation. The Booker of “Corrected” says with his whole body that the Booker of “Black Bird” has a future — that there will be great struggle, but also ease.

It is tempting to say that Fifteen is predominantly about resilience and perseverance. But the word that instead keeps coming up for me is care. While Booker is represented in these two monumental oil paintings, he conceals himself in other pieces of new work in the show. He paints the people who supported him — his mother, grandmother and wife, as well as teachers and friends. Booker paints his own figure too. We see his clothing — a prison uniform here, a smart gray suit there — but his face, his hands and arms are concealed by pastel flowers. These appear symbolic of the support he felt from his family and community in the space and time between “This Black Bird” and “Corrected.” It’s a risky gesture that pays off — though I might like it more if the flowers were less impressionistic. Overall, the portraits are love-drenched and celebratory — with sunny shades of yellow, bold pinks and lush greens.

It wouldn’t be fair for me to write this without telling you that Omari is my friend. We talk on the phone for an hour or so once, maybe twice a year, and we check in by text occasionally. He’s the kind of person who remembers details and is sure to tell you why you matter — to him, to the world. He is honest and transparent, and it’s impossible to be shifty or shady with him. And it’s impossible to lie.

Seven years ago, I classified Booker’s paintings as earnest. Eagerness and sincerity aren’t exactly prized in contemporary art, and he sometimes relied on cliché and heavy-handed symbolism. But he kept painting, developing his chops and moving toward something more original and meaningful. As his practice deepened, it became clear to me that being sincere is not the same thing as being naive, and the works’ earnestness was intrinsic to Booker’s nature. By that point, art had already been saving his life for a decade, and it wasn’t eagerness but urgency propelling him forward.

The hallway gallery at Elephant traces Booker’s emergence as an artist by showing older works beside more recent paintings. Some are sketches on blank prison travel permits and parole reporting forms — signs of an artist making do with what he had. This section is autobiographical in a way that I understand, but that I resist. I want the story to be told only through the new work — the towering portraits, the women who loved him into existence and kept him alive. It was important for him to show the whole story, including uncertain beginnings, and there’s value in that.

It is socially significant that Fifteen is on view in the white-owned Elephant Gallery in the historically Black 37208 ZIP code. It is among the ZIP codes with the highest rates of incarceration of young adults in the nation. Located near Fisk University, it is also in the neighborhood where Black student-activists were trained in nonviolent protest by James Lawson and planned the lunch-counter sit-ins and Freedom Rides that desegregated Nashville and the South. And it is also the neighborhood that the state bisected with I-40, killing Black businesses and amputating the limbs of a thriving community. There is struggle, yes, and there is power, and there is also ease. Fifteen is about walking through it all.