“Bleeding and Crying,” Kimia Ferdowsi Kline

Off-Site is an ongoing series of features about Nashville-based artists whose work is being exhibited elsewhere.

Heritage informs the art of Nashville native Kimia Ferdowsi Kline — but maybe not the kind of heritage you’d expect. She was born and raised in Davidson County, but Kline’s family is Persian, and her mother was raised in Africa. Those influences, combined with a childhood that was spent with more access to her family’s medical practice than contemporary art, formed the basis of Kline’s singular style, which is both offbeat and sophisticated, rough-edged and profound.

“I’m very influenced by outsider artists,” Kline tells the Scene during a studio visit in her family home in Brentwood. “I didn’t even know that there was a contemporary art world until I was 17. All of the art that I was exposed to growing up were Persian miniatures, Persian rugs, Persian calligraphy. I didn’t know that art continued after Van Gogh. I just had no idea. So Mose Tolliver, Clementine Hunter, Jimmy Lee Sudduth — those were my heroes.”

The Southern outsider-art influence is clear in a work like “Bleeding and Crying,” its flat figure brought to life with a kaleidoscopic Minnie Evans color palette. This painting is one of three that are part of To Make Me Forget About Now, a group show curated by Jordy Kerwick that opens Saturday in Paris. In the painting, a crouching figure bleeds from its vagina, leaving a trail of bright red that matches its naked breasts. That trail is repeated in tears running from the figure’s eyes, gracefully curved like fabric tied up in a canopy. Despite its bloodied, teary-eyed state, Kline’s figure never seems pitiable. The artist’s ability to portray a figure’s powerful energy even in a compromised state might come from her family’s history in medicine — to a physician, blood can be a byproduct of healing, not necessarily a signal of danger.

"Four Generations in a Barn," Kimia Ferdowsi Kline

“My grandfather was a surgeon, and my mom is a nurse,” Kline explains, “so I also come from a very medical family. We have different ways to talk about the physical healing of the human body, and I have a very visceral connection to that. I’m interested in the intersection between beauty and pain, wounds and healing.”

Another connection between surgery and Kline’s artwork is her inclusion of stitching. She uses book-binding methods to literally stitch through the parchment she paints on — a skill she picked up during the year she worked as a bookbinder after graduating college. The resulting grid-like structures make Kline’s paintings feel pored over and somehow human. The papyrus she uses as canvas — she sources all her papyrus from an Egyptian vendor named Mustafa — is a perfect stand-in for skin.

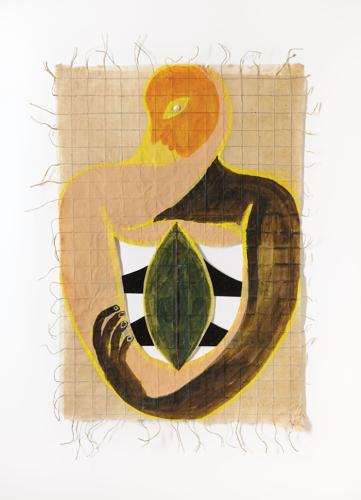

“I Didn’t Come From Your Ribs, You Came From My Vagina,” Kimia Ferdowsi Kline

“I think about skin tone a lot,” she says. “I just think about all the different beautiful skin tones in the human family. So when I’m making paintings, the skin tones are intuitive, but they’re also formal. But I’m also thinking about depicting skin in different ways, and always making sure that there’s a diversity of color that I’m using for that reason.”

With “I Didn’t Come From Your Ribs, You Came From My Vagina,” the stitchwork forms a precise grid that underscores a formalist balance — it’s not a stretch to compare the figure to the traditional symbol for yin and yang. The figure seems saintlike, her freshwater pearl eye glistening as she gazes down toward an earthy vaginal shape that looks a bit like the waxy leaf of a Southern magnolia tree. It’s a bold, prophetic vision that perfectly encapsulates Kline’s own multilayered, multicultural origins.