Identity is not always easy to define. On some days, we may think we know exactly who we are. But at other times, it requires removing masks we didn’t know were there to truly understand ourselves.

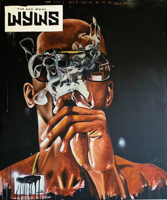

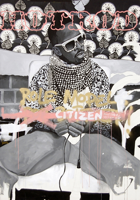

This idea is explored in an exhibition by Atlanta-based artist Fahamu Pecou at the Frist Art Museum. This Face Behind This Mask Behind This Skin displays paintings, sculptures and other mixed-media pieces, many of which come from Pecou’s series End of Safety, Real Negus Don’t Die and We Didn’t Realize We Were Seeds. Each piece works in conjunction with another to examine Black identity, masculinity and cultural and ancestral influences.

“What I’m attempting to express through the exhibition is a kind of removal of the kind of external influences and voices that shape our identity, so that we can really interrogate the internal one, and in that discover who we truly are,” Pecou tells the Scene.

Pecou experiments with the idea of Afrotropes, a concept first named by art historians Huey Copeland and Krista Thompson to describe recurring visuals that have become symbols and icons within Black culture and history. This is seen as Pecou depicts objects like durags and cowrie shells throughout the exhibit, attempting to reshape their traditional associations.

“Rather than just thinking about them as an aesthetic, I have been thinking about them as kind of like ritual objects, like this power invested in these symbols to have deep resonance and meaning,” Pecou says.

The majority of Fahamu Pecou's paintings are self-portraits. But for an artist who goes by the Twitter alias Fahamu Pecou Is the Shit, he spea…

“I’m really sort of [invested] in transforming some of the ways we think about Black identity and Black culture, moving it away from a language of lack or trauma,” he adds.

The exhibition also features the debut of the artist’s short film “The Store,” a 13-and-a-half-minute Afro-surrealist picture that centers on a bodega. For sale inside the store are fictional Teacha-brand products, which transport users to a magical alternate reality. With monochrome and shimmering imagery, visitors of the store experience visions connecting them with Black ancestry and spiritual identity.

When visitors walk into the exhibit, they are immersed in the store — soda cans and cereal boxes adorned with the Teacha logo line shelves along the walls.

Three separate rooms make up the exhibit, filled with artwork that employs a wide range of artistic mediums that all come together to tell a larger story. One wall displays three transparent backpacks sitting atop books. Inside the bags are resin sculptures, cotton and an Arizona Iced Tea can — all providing a glimpse inside our identities as defined by the objects we carry.

Another wall features Pecou’s 2014 painting Elevation of Fetish, which bounces off the wall via its vibrant yellow background. The piece draws on Air Jordan 1s as another example of an Afrotrope. Other acrylic pieces depict bright shades of blue, pink, purple and green, standing out among the Frist’s white walls and also providing a contrast among the exhibit’s recurring theme of positioning ourselves behind a mask.

Plastered along the wall just above one of these paintings is a James Baldwin quote: “Love takes off the masks we fear we cannot live without and know we cannot live within.”

At the center of another room is a large resin sculpture that depicts a person sitting down as they grasp a long, flowing veil covering their face. Visuals like these are apparent as you stroll through the exhibit, and come to reckon with the masks we all wear — and what it means to release ourselves from those veils of identity.

Pecou says while much of the work emphasizes experiences within Black culture, it also points toward humanity as a whole.

“I also assume a responsibility to define or redefine that for myself — the right to not live in someone else’s idea of who I should be or what I can be,” Pecou says. “And I think that every single person on this planet, one form or another, asks themself that same question. It is a universalism that goes beyond skin color. It could be your spiritual identity, it could be your sexual identity. It could be your political identity. Whatever it may be, you at some point have to break with all of the ideas that you believed in order to determine and define for yourself who and what you are.”