"Being and Knowing I Have Been," Ashley Doggett

A turning point for Ashley Doggett’s art occurred before she’d even started art school. The February before Doggett began her freshman year at Watkins College of Art, Design & Film, 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was shot and killed. That 2012 incident, and the Black Lives Matter movement it propelled, changed everything. When she got to Watkins, Doggett was among only a handful of black students; when she graduated, she was the only person of color in the entire fine arts department. So when you ask her why she chooses to paint such emotionally loaded subjects — black slaves and white masters, black women made up to look white, and lots and lots of chains and shackles — it’s no surprise that her answer is stunningly simple: She’s just trying to be honest

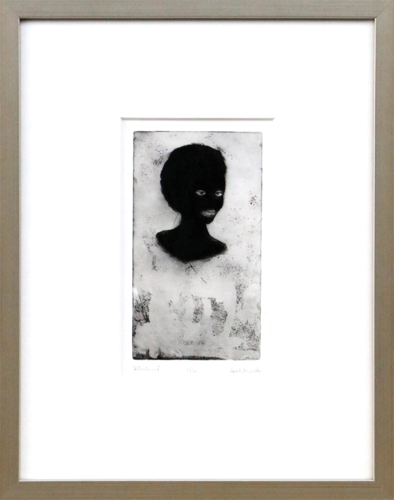

“Blackened,” Ashley DoggettCourtesy of David Lusk Gallery

“I love when people can be honest with each other,” says Doggett, sitting with her legs crossed on a leather sofa in her home in Madison. “That’s how I approach my own work as well. Whether that be my own truth, or the truth of what it is — I’m just saying it, and making it approachable.”

Doggett is disarmingly direct, diving deeply into conversations about her work. At one point in our conversation, she discusses being a well-spoken black woman, describing the microaggression of a white person calling her “articulate” — the implication being that her eloquence comes as a surprise.

“I think that as artists, we’re made to be historians,” she says. “We’re made to be perpetrators, and also to talk about these things. As an artist, you have to show others what’s going on in the times. It’s a record — a human record. Someone could see [your work], and they’ll know exactly what’s going on in the times — what was happening with you and your culture. Artists are definitely historians in that regard, and whether that’s a burden we have to carry or not, it’s just part of it.”

Her first solo show, organized at Nashville’s Channel to Channel gallery while Doggett was still a student at Watkins, was notably ambitious — big canvases, bold colors and even bolder subjects. A frequent image in these early paintings is black women in whiteface makeup, as in “A Scourge of Antiblackness and Self Hate, Courtesy of Master Leeroy.” Doggett’s portrait of a woman with a candy-pink coiffure sits in front of a pattern of blackface cartoons, ropes and chains, her face like a mask of white makeup that looks like it’s been erased from the canvas.

“People will be uncomfortable if their ideas behind racism and discrimination have been sugarcoated,” she told me after that show in 2017. “People will be angered if their racism is being called out as hateful and utterly disgusting. I’m prepared for it all.”

Art dealer David Lusk, who owns galleries that share his name in both Memphis and Nashville, knew Doggett was special when he first saw her work. He now represents Doggett, and will be hosting her second Nashville-based solo show in the fall.

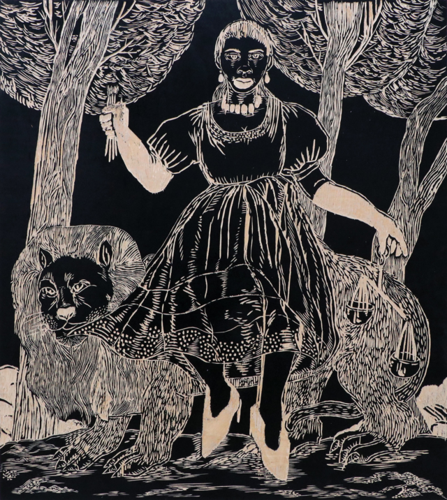

“Good Lookin Gyal: Buju title Banton, Leo and Time,” Ashley DoggettCourtesy of David Lusk Gallery

“The work has changed a lot just in the last two years,” says Lusk at his gallery in Wedgewood-Houston. “And I get the feeling that she’s not afraid of that — of getting better in her storytelling.”

Lusk loves Doggett’s work, pulling out two etchings the artist made while still in art school. One of them, “A Fire Consumes Her Before She Sobs,” was just sold to a family of African-American collectors. “It’s not an easy work to live with, but it resonates,” Lusk explains, referring to the etching’s image of a bare-breasted black woman with tears streaming down her cheeks. The etchings and woodblock carvings in Lusk’s archive are charged with power and talent, but it was Doggett’s paintings that first resonated with him.

“She has this haunting blend of the fairy tale and the Bojangles imagery,” Lusk explains. “They’re provocative in that you’re not sure what they present, and what take she’s going for with it. She’s mining depths in a more palatable way than a lot of similar Black Lives Matter works.”

Something Doggett returns to again and again in her work is the style of slavery-era America.

“I want to look back on that history and also have commentary on this notion of African-American people reappropriating colonial standards,” she says. “I think that’s something that [African-Americans] do inherently, in the wake of not only not having our own culture, but also of surviving within something that’s very suffocating. It’s a means of having something when you haven’t been allowed to have anything. And coping with this feeling of, ‘I have nothing, let me take something and make it my own.’ It’s almost like an ouroboros.”

That’s Doggett’s work in a nutshell — images that are fighting for and against their own beauty, struggling against traditional representations of race, gender and class. But somewhere in the process of that struggle is the realization that belonging was never the object of the game — it’s about subverting the game, and eventually destroying it. Doggett is here to fight.