In December 1961, the exhibition Art From Africa of Our Time opened at the Harmon Foundation in New York. Earlier that same year, the Freedom Riders began protesting segregation across the American South, and the Museum of Modern Art exhibited its first work of contemporary African art. That convergence is more than coincidence. The liberation of several African countries from colonial rule occurred throughout the early midcentury, and travel between the U.S. and African nations began to open up. Africa — its artists and thinkers — were able to influence America in ways that would have been impossible just years earlier. The impact of that influence is massive, and is the first thing you notice when viewing African Modernism in America, another landmark exhibition, which is on view through February at Fisk University Galleries.

Afi Ekong, “Olumo Rock”

Among the exhibit’s first highlights is Nigerian artist Afi Ekong’s oil-on-canvas painting “Olumo Rock,” from 1960. At first glance it appears to be an abstract assemblage of color, but Ekong, who also went by Constance, named the work after a famed mountain in Nigeria that provided protection to residents during the 19th-century Yoruba civil wars. The painting, at roughly 10 by 30 inches, is a jewel, and almost appears multifaceted — expressive brushstrokes of orange, purple, green, red and blue are outlined in black, swirling with the energy of a van Gogh sky. Just as informative as the title card is a note that the painting was recently conserved. To help ready the work for exhibition, Fisk received funding from multiple institutions, and students from across the campus — art students and math students alike — were able to assist in the painting’s conservation.

Just a few feet down from the Ekong canvas is a pair of works from two more Nigerian artists — a carved chess set from Justus Dojumo Akeredolu and an oil-on-canvas painting by Akinola Lasekan. The painting, called “Ogedengbe of Ilesha,” was also conserved for this exhibit with help from Bank of America, and portrays a hero of the same 19th-century Yoruba wars that informed Ekong’s piece. In this work, Lasekan has realistically depicted a battlefield populated with marching warriors, musicians midsong and vast, atmospheric space. The artist’s background was mainly in commercial illustration — he wasn’t formally trained in Nigeria, but instead earned certificates in international correspondence courses. That academic aptitude serves the history painting well — its composition is complex but harmonious, and elements borrowed from Lasekan’s career as a political cartoonist blend seamlessly, like the lines of smoke that rise from the rifles, and the expressive faces of the musicians.

Akeredolu’s chess set may seem a strange companion piece to the massive history painting, but its placement just underneath highlights the metaphor of war as a kind of game. It’s also a fascinating piece of craftsmanship — the king pieces’ eyes peer out over a face covering that seems almost translucent, and each of the pawn figures are young boys seated in different postures.

“Vision of the Tomb,” 1965. Ibrahim El-Salahi (Sudanese, b.1930)

Oil on canvas, 36 x 36 inches, Collection of The Africa Center, New York,

2008.2.1 Photograph by Jerry L. Thompson

© Ibrahim El-Salahi All rights reserved, ARS, NY 2022

Courtesy Vigo Gallery and American Federation of Arts

Ibrahim El-Salahi is one of the only artists to have multiple works in the exhibition. That inclusion honors his importance — the Sudan-born, U.K.-based El-Salahi was the first African artist to have a career retrospective at the Tate Modern in London, and he currently has an exhibition of works on paper hanging at The Drawing Center in New York. The artist’s father was a Muslim cleric, and as a result El-Salahi was deeply familiar with both the Quran and esoteric Sufi philosophy. So while he studied at the Slade School of Fine Art in London in the 1950s and also lived in the U.S., Mexico and Brazil, undercurrents of Arabic iconography are evident in the two African Modernism paintings.

His 1965 painting “Vision of the Tomb” is a 36-by-36-inch abstract masterwork that incorporates El-Salahi’s signature calligraphic flourishes with totemic stacks of color that seem to disappear into mist. The painting also has an exceptional provenance — it was painted while the artist was living in New York as a Rockefeller fellow, and in 1967 MoMA curator Dorothy Miller recommended that David Rockefeller purchase it for the Chase Manhattan collection.

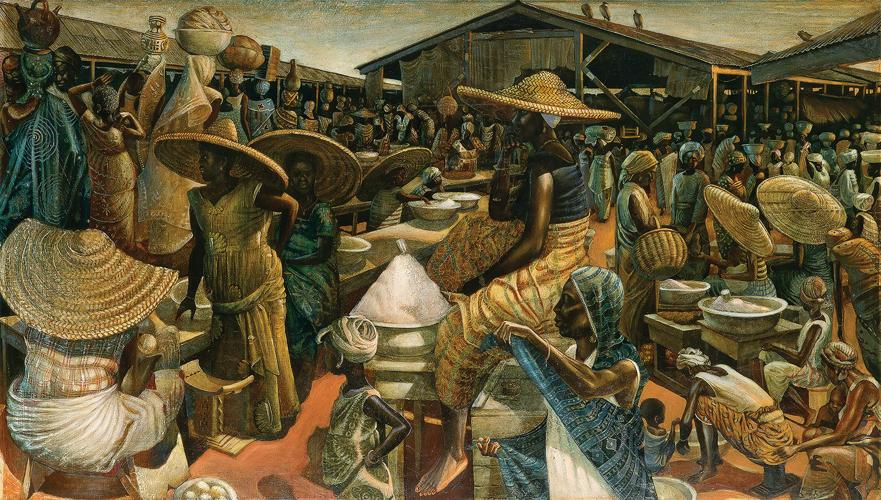

Another painting with a notable provenance is the massive “Kumasi Market,” painted in 1962 by African American artist John Biggers. The 34-by-60-inch work was once owned by Maya Angelou, who purchased it directly from the artist. Biggers is one of the few African American artists known to have traveled to Africa by the early independence era — “Kumasi Market” was based on the artist’s travels to West Africa in 1957, the same year Ghana gained its independence from Britain. During his travels, Biggers made extensive sketches, and collaged them together to create the panoramic scene of a bustling marketplace.

The details are compelling — you can tell that a storyteller like Angelou would find a lot to be interested in. The calm center of the painting shows a woman quietly balancing a pencil-thin scale in her hand. There are other vignettes, like a bird ruffling its feathers on a rooftop, a woman struggling to squeeze through the crowd, another woman tying a shawl. According to text from scholar Alvia J. Wardlaw, “Angelou cherished the painting, which remained a source of personal inspiration for her. She once recalled to me how the woman [holding the scale] in the painting greeted her with an eternal calm when she returned home from her frequent travels, providing a moment of spiritual renewal.”

This exhibition was years in the making, and is extensive enough to require multiple visits. There are two floors of work, a timeline that unfolds along the wall of a staircase, woodcuts, collages, ceramics, ephemera and plenty of photographs that add contextual importance — including some that document African artists during trips to Fisk.

In one document from 1962, Aaron Douglas — founder of Fisk’s art department and a major figure in the Harlem Renaissance — wrote, “There is a tremendous interest in African life in America today, and art is an excellent vehicle for keeping this interest alive and going.”