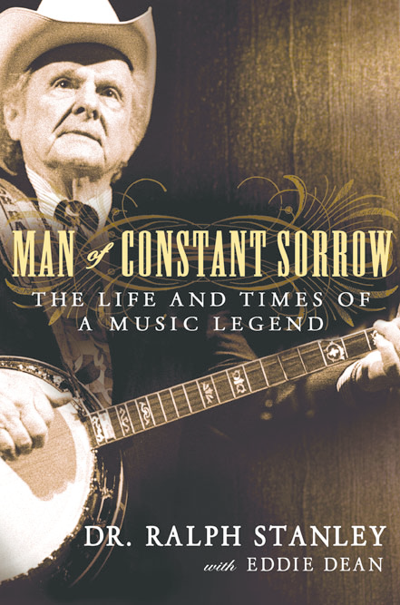

When he was a child, he was often called "the boy with the hundred-year-old voice." At 82, Dr. Ralph Stanley remains younger than the sound of his singing and continues to travel the world performing for capacity crowds.

In his new autobiography, Man of Constant Sorrow, Stanley recounts a career spanning six decades and millions of miles. Ralph and his brother Carter formed the Stanley Brothers in 1946, at the birth of bluegrass, and quickly made a name for themselves with songs such as "White Dove," "Rank Stranger" and "Man of Constant Sorrow." Following Carter's death in 1966, Ralph forged ahead and hasn't slowed down. He won a Grammy Award in 2002 for his performance of "O Death" from the soundtrack to the film O Brother, Where Art Thou?

Man of Constant Sorrow puts the reader in the passenger seat as Stanley spins tales of life and loss on the road. Though he's lived in Virginia most of his life, Stanley and his band were for years based out of Bristol, which straddles the border between Tennessee and Virginia. On a recent break from touring, he took a moment to speak by phone about Man of Constant Sorrow and to discuss music, the road and his remaining goals:

The Stanley Brothers first became well-known through radio shows like the Farm and Fun Time show on WCYB in Bristol. What were those shows like?

There was a new station that went on the air, WCYB, and they was gonna start this show. We just happened to go up there; we had WCYB on our mind, too. And they auditioned us. We done a couple of tunes, and they said, "You're hired. Want you to start tomorrow." The show was an hour-and-five-minutes long, so you know we was dreading the time being so long. But we started the show at midday, 12:05 Farm and Fun Time, and we played the show there by ourselves for over a year. It was a good time slot, because that's when everybody would take their lunch break and could go inside somewhere and listen to the radio.

That show got to be so popular, they got so many sponsors that they had to extend it to two hours. So we started the two-hour show, but we told them we needed some help. There was a lot of people, musicians, that came there to get a spot on the show. But we still kept our hour, and we played Farm and Fun Time off and on for 12 years. It did a lot for us. It was a new station at the time, and our father had handbills made and took around over the region. He was booking shows for us at schools and so forth, and took the handbills to stores and other places talking about the new station and the new show.

So the radio show brought a great deal of exposure, and then you would go out on the road and play schoolhouses and churches.

Yeah, right.

Would you describe a typical day back then? What was it like traveling to all those shows?

Well, they wasn't too far apart, but back then we were playing six nights a week much of the time. Bristol, on the border of Virginia and Tennessee, was centered there near Kentucky, West Virginia and about four states. So we could travel that whole region. We would advertise for shows, anybody who wanted to sponsor us at a show. We got so many offers, we had to throw some of them in the waste can! Yeah, we would travel and play six days a week, sometimes seven days a week. That helped make the Stanley Brothers. And I think the Stanley Brothers helped make WCYB.

In your new book, you talk about how the Stanley Sound, as it came to be known, is really rooted in a deep sense of place. How do you think the Clinch Mountains, where you were born, influenced your sound?

Well, I guess the mountains and mountain culture had a lot to do with it. Carter, my brother, he wrote more songs than I did. I wrote some too, but we wrote the songs just like we were raised. It just come natural for us, and I think our upbringing had a lot to do with it.

You write in the book, "Seems like country people are most happy when they hear sad songs." Why do you think that is?

I don't know, I just think this old-time sound just gets with them and helps them forget their troubles and so forth. Even though some of them are tragic songs, I think they like the melodies. I think they pay more attention to the melody than they do the words. The Stanley Brothers, not bragging or anything, had a sound that had never been before. I'm proud of it. It was our own sound. We didn't copy anybody. Now maybe our first six months or something, we had a mandolin player that sounded like Bill Monroe. But after he left, then we got to settle down to just Stanley sounds.

You were definitely originals.

That's what people tells me, and that's what I think. I'm proud that God gave us a sound of our own.

I'm glad you mentioned that. A lot of your sound comes from the church, specifically the Primitive Baptist tradition. Would you describe that style of singing?

Well, I'll try to. Primitive Baptists don't believe in instrumental music in the church. We sang songs much like they did. They had their own natural sound, put it out just like they felt it. The Primitive Baptist sound is different than any other church. That's actually what gave the Stanley Brothers a lot to go on.

How has the industry changed from when you first started?

It's changed a whole lot, you know. Now we play big auditoriums and halls. But what I notice most, back then we had five or six men humped up in a sedan car going out to shows. Now I have an air-conditioned bus with bath and everything. We travel more miles, but it's so much more convenient. A lot easier, even though it's farther.

After 63 years, are you ever surprised by anything that happens onstage?

Not really. I think I've seen about all of it. We just go out and do the best we can. I'm fortunate now that we draw capacity crowds about everywhere we go. And they enjoy the show and applaud for you, and it makes you work harder, you know, to please them.

You're a legendary musician, you have an honorary doctorate degree from right here in Tennessee, and now you're a published author. You're not slowing down a bit. What's next for you?

Well, I guess I'll just continue what I'm doing, you know. Actually, I don't know of anything much more that could happen. Well, I'll tell you one more thing I'd like to have, and I think I deserve it, and maybe it'll come sometime. I'm in the Bluegrass Hall of Fame, but I'd like to get into the Country Music Hall of Fame. That's really the only thing I can think of.

For more local book coverage, visit chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.

Email arts@nashvillescene.com