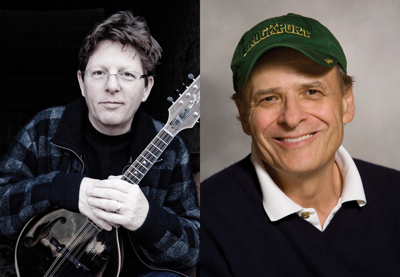

For more than 30 years, Tim O'Brien has been regarded as one of the definitive voices of the Vietnam War. A literary trailblazer, he melds fact and fiction in texts that are both starkly realistic and surreal. Winner of numerous awards and honors, including a National Book Award for Going After Cacciato (1978), O'Brien is best known for The Things They Carried (1990), a postmodern hybrid of novel and story collection that has become the most widely read and influential work of fiction on the American serviceman's experience in Vietnam. In anticipation of his forthcoming visit to Nashville to share the stage with Tim O'Brien, the equally legendary Nashville musician, at a special benefit in support of The Porch Writers' Collective, the novelist answered questions from Chapter 16 via email.

Next year marks the 25th anniversary of the publication of The Things They Carried. That book is regarded not only as the definitive work of fiction about the U.S. infantryman's experience in Vietnam, but also as a landmark in American literary narrative technique. How has your view of the book evolved in the years since you conceived it? When you set out to write it, could you ever have imagined that it would become a classroom staple at both the college and high-school levels? I'm delighted, of course, that The Things They Carried has found a sustained readership. (Authors wouldn't publish books if they didn't want people reading them.) I am surprised, though, that TTTC appeals to so many college and high-school students. At least in part, the book is about epistemological ambiguity — What is true? What is truth? Does "truth" evolve? How do we know what we know? — and I had imagined that such questions would frustrate a younger audience in search of absolutes. As I wrote the book, I think I envisioned a pretty sophisticated "literary" readership, if any readership at all. My view of the novel itself has changed little since its publication. The main surprise, I guess, is that I can still read it with an occasional smile of pleasure.

When I first talked to you a little more than 10 years ago, you spoke about the relationship between the Vietnam War and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, which were then just beginning. Looking back as a veteran and a fiction writer whose career has rightly or wrongly been defined by your military experience, how would you summarize your feelings about the way our country has used and is using its soldiers in the 21st century? I'm incapable of summarizing my views about the way our country has used and is using soldiers. I'll just make a couple of observations. Wars are without exception sold to us as pending catastrophes. We're told that if we don't go off killing people, terrible things will ensue — dominoes will fall, liberties will be lost, towers will tumble, the streets of San Francisco will be teeming with Viet Cong, mushroom clouds will blossom over Manhattan. Occasionally such dire forecasts contain at least a grain of truth. Most often, not. I'm sickened that America was bludgeoned by the rhetoric of fear to fight a war to get rid of weapons of mass destruction that did not exist.

I'm more sickened that no one seems to care. It would be as if my father had enlisted in the Navy in 1941, only to find out two years later, as he dodged death off Iwo Jima, that the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor had never happened. Or another example: I own a white dress shirt that has a little tag in the collar that reads "Made in Vietnam." My wife bought the shirt for me at a J.C. Penney store in Austin, Texas. Catastrophe? We lost that war — the worst imaginable outcome occurred. So where's the catastrophe? Three million dead Vietnamese, almost 60,000 dead Americans, and 40 years later we're buying dress shirts at J.C. Penney that were manufactured in Vietnam. Business is booming. Suburban high school kids bicycle up and down Highway One in Vietnam. American tourists eat noodle soup in Ho Chi Minh City. Exchange students from Hanoi study in American high schools and universities. Where's the goddamned catastrophe? Who among us wakes up each morning and thinks, "Oh, dear, we lost in Vietnam, my liberties are gone, my life is ruined, America has been wrecked by the Viet Cong?"

At your forthcoming appearance in Nashville, you will share the stage with another Tim O'Brien, the renowned bluegrass musician. I've read that both of you have received each other's fan mail for years but have never met. Could you make something like this up? I've received a fair number of email messages that were intended for Tim O'Brien, the musician. Even a few phone calls. And I understand that he — the "other" Tim O'Brien — has undergone the same experience in reverse. I'm thrilled that we'll finally have the chance to share a laugh about this.

The event will support The Porch Writer's Collective, a nonprofit literary center in Nashville designed to encourage and support the efforts of aspiring writers. What's the best advice or encouragement you can offer to writers just starting out? I have sparse advice for those who wish to write fiction. Be a mule — be stubborn. Read a great deal and pay attention to how other writers do the things they do. Be a mule — be stubborn. Learn your grammar. Be a mule — be stubborn.

To read an uncut version of this interview — and more local book coverage — please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.