For a few months in 2005, book art seemed to be all over Nashville. The Main Library, the Tennessee Arts Commission and TAG all had shows of artist-made books, as if they had coordinated schedules. It's like when every studio in Hollywood puts out a movie about an asteroid hitting the Earth. This summer the asteroid is drawing, with group shows at Estel and Zeitgeist, a four-person show in the Frist Center's CAP Gallery complementing the Color Field show, and even Glexis Novoa's drawings on marble at Cheekwood.

Estel Gallery has put on one of its most ambitious shows so far, a group show of drawings selected from an open call for submissions. Gallery owner Cynthia Bullinger chose work by 14 artists—a few local, most not, and most new to Nashville audiences.

Shows like this usually take on a loose structure, unless the curator has a distinct ax to grind. The work in Estel's show revolves around two poles—on one end a very modern reticence, on the other an equally contemporary effusiveness.

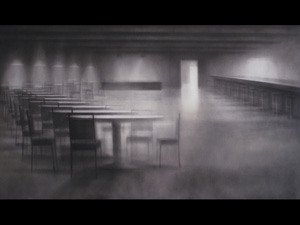

On the understated end of the spectrum is Maggie Evans, an artist from Savannah, Ga., who showed at Dangenart in 2007. She sings in a blues band and makes charcoal images of the clubs in off hours, before or after the patrons have arrived. Interior details are partially erased, so they seem to float in the space, spectral landscapes for ghostly inhabitants.

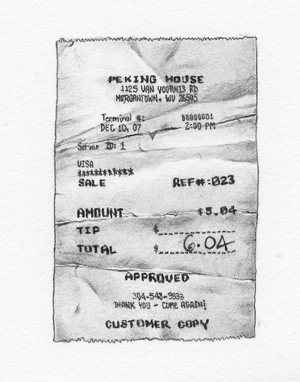

Understatement is expressed differently in Joseph Lupo's drawings of store receipts. Lupo draws with care, capturing the text and the crinkled paper of mundane register receipts. They share much in common with Cheyney Thompson's celebrations of the ordinary, themselves inspired by Baudelaire.

The self-portraits by Jodi Hays (director of the art gallery at TSU) might seem anything but reticent. They are big and life-sized—and what could be more revealing than self-portraits? What's more, in one piece, the artist poses in lingerie. But the images are created with light markings, so they almost fade out in places. Hays uses just enough graphite to put the image across, seeming to expose herself but really withdrawing from view. As subject of the pictures, she stands off, tilting her head in poses that express wariness or skepticism.

On the other end of the spectrum we find effusive and expressive pieces by several artists. Patrick Gabler's large, attractive abstract drawings consist of circular forms made from feathery ink strokes. Tadja Dragoo's "Neural Communication Tower" cobbles together bits and pieces of antennae, satellites and electrical components into the form of a neural network, Piranesian in its detail. Rhett Gerard Poche makes explicit reference to the baroque era in his drawings of young men and women making faces at the viewer, wearing wreathes in their hair and goofing around with common objects like funnels and Corona beer bottles.

David Hellams, a recent Sewanee graduate, makes the best use of a baroque sensibility. Some of his figures twist and turn in ways baroque artists used to introduce tension and energy into their compositions. "Eternal Replay '86" shows two football players, one diving through the air parallel to the ground, arms outstretched, with another player grabbing him by the legs. He is reaching not for a football, but a bonsai tree. Hellams details the player's expression under the helmet, wide-eyed with surprise and concentration. The piece thrusts together the disparate worlds of classical figure drawing, football and Japanese miniature trees. There are many references here—to the way video allows us to make an ephemeral moment eternal, the way popular culture and high art get mixed up, and the way modern cultures intrude upon each other.

The two poles of reserve and effusiveness come together in the work of Marcelo Halmenschlanger, another Nashville artist. His figures have the erotic spirit of the 19th century decadent movement. (Think Oscar Wilde.) The subjects are nudes, men and women, with surreal details and classical references, and include strategically indistinct areas that make it hard to tell how graphic they are. "Modern Centaur" shows a male torso leaning backward in an ecstatic pose. In place of a horse, his lower body is formed from a motorcycle. You can't be sure whether the area where his penis would be shows genitalia or the mudguard of the bike's front wheel. The erotic character of "Sailboat Boy" is perfectly obvious from the title, and the image—a young man (with a sailboat perched on his head) looking downward and resting his hand near his hip—could imply that the guy is masturbating, or that he's one half of a couple having sex. The ambiguity of these drawings heightens the pervasive eroticism.

Shows like this serve multiple functions: They give the gallery a chance to exercise curatorial creativity and to make points through the selection and juxtaposition of work, while introducing some new artists to the gallery and the city.