There's a moment during Howard Finster's 1983 appearance on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson — after his open-armed entrance and the "I never dreamed of being on your show" small talk — when the pomade-slicked folk artist picks up a banjo and begins to sing in front of Carson's desk, and all of a sudden the roles reverse, and Finster is the showbiz superstar, and Carson is just trying to stay in the frame.

That was the charm of Howard Finster. He was so grounded in Southern traditions that his eccentricities seemed like good old-fashioned storytelling, and so otherworldly that his conventional methods seemed like starry-eyed mysticism. His artwork is pure folk, overflowing with images of Daniel Boone and biblical allegories — and yet he paints Elvis and flying saucers alongside Jesus and his angels. Because to Finster, there's not much difference between those worlds.

Stranger in Paradise, Tennessee State Museum's exhibit of the self-taught artist's work, is vast, and incorporates video, sculpture, works on paper, album covers (including R.E.M.'s Reckoning and Talking Heads' Little Creatures, which features an Atlas-like David Byrne holding the world on his shoulders while wearing nothing but work boots and white underpants) and more paintings than seem possible for one person to produce in a single lifetime. Howard Finster kept himself busy.

In 1977's "Bring the Inside Out," one of the first pieces in the exhibit, Finster explains how he discovered his talent for painting just a year earlier. "One day I dipped my finger in white paint and there appeared a human face on the round tip of my finger. A feeling came over me to paint sacred art." From then until his death in 2001, Finster produced more than 46,000 works. At some point he began numbering the paintings, so in addition to the date, the chronological number is listed in the museum signage, and sometimes on the paintings themselves.

Like a church's stained-glass story panels or William Blake's illuminations, Finster's paintings are meant to work like visual sermons. "Shortest Message Up. Or. Down." was his 6,928th painting — a vertical skyscape of tractor paint on a wooden plank. When you follow the figures he's painted — swaths of bright colors like stick figures or a Barrel of Monkeys game — your eyes can go up or down, to heaven or hell. To go up means churches on clouds, moons, stars and rocket ships alongside phrases like "comfort," "no canser," "Jesus in person," "no wars" and "no funerals." Below that, the paint turns a bright red, the figures become more crowded, and the words change to Dante-esque terms like "suffer," "groans," "screams" and "separation," and the purely Finster-esque "no cold Cokes." In the middle of the painting is a spherical planet, which Finster has labeled "Earth in space." In a Finster painting, the space between biblical mythology and science fiction is similarly measured — worlds apart, yet able to exist on the same plane.

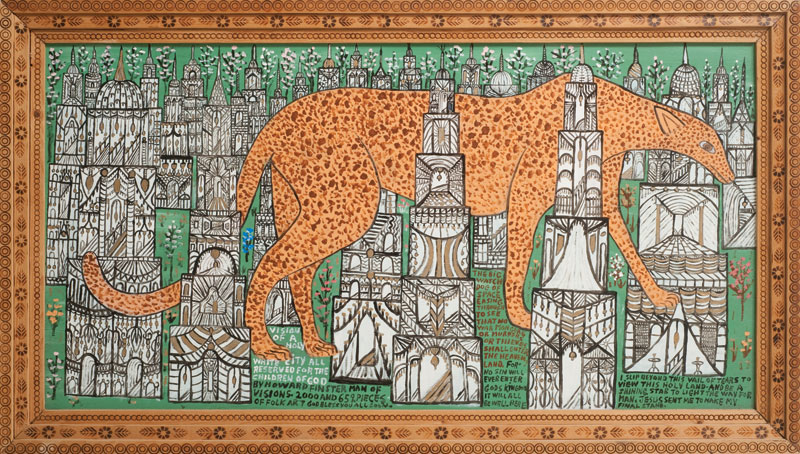

Because Finster didn't separate the divine from the earthly, he incorporated cultural and religious figures with the same amount of fervor and beatitude. Elvis was a frequent subject, but the Tennessee State Museum includes examples of Finster's renderings of characters as disparate as Henry Ford and Santa Claus, JFK and Mona Lisa. In "Vision of Daniel Boone," he paints the historic figure surrounded by seven howling wolves, posed in front of a fantastical cityscape filled with people flying from building to building, the architecture as intricate and imaginative as anything by Hieronymus Bosch.

The frequent misspellings in Finster's text-heavy paintings add to the candid, stream-of-consciousness quality that grounds him firmly in the outsider art movement, even as he transcends its limitations. The huge wooden canvas of "Sneakers," from 1981, features a vast blue sky that is uncharacteristically empty of words. It says simply, "I believe in other worlds." Below that, Finster has painted a vision of battleships amid a crowd of Loch Ness-style water dragons. "Strange beast rising from the sea," Finster calls them, and then asks, "Are they kemical kings or desease."

Finster commemorated his appearance on The Tonight Show, of course, with a piece of art. "Howard Was on Johny Carson Show" was Finster's 3,868th work. Cheetahs march along the bottom of the painting, just below a road full of people walking forward, arms stretched over their heads, filing past a sign that reads, "The people's road goes right through Johnys spirit." A portrait of Carson is on the right, and written across his chest it says, "I like Johney." What's harder to make out are the words along the margin next to this. Barely legible, Finster has marked with an uncharacteristically faint brushstroke, "What a fast world." For Finster, the man who looked at the world with such strange fascination that he was compelled to spend his last years hunched over wooden panels with paint-covered hands, the spectacle of television was like a vision of the future. Finster was just trying to keep up.

Email arts@nashvillescene.com.