Streaked, bright-green hair tied into a low ponytail at her nape, a bored-looking teenage girl adjusts the dozens of plastic studded bracelets on her right arm, then starts to fill in the white rubber of her black Chuck Taylors with red-inked swirls and checkerboard patterns, dotting the soles with tiny words. Drumsticks lie in wait in her lap. As the auditorium where she sits begins to brim with more girls her age, her hardened expression visibly softens: These girls listen to the same bands—it says so right there on their T-shirts. Just like her, most of the new arrivals look wary and aloof when they first enter, weighted down by large amps or guitars strapped to their shoulders, but their mounting excitement chips away at their practiced veneers.

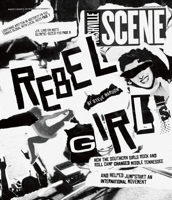

It’s July 28, the first day of the first-ever Southern Girls Rock ’n’ Roll Camp, a five-day event organized and directed by Middle Tennessee State University junior Kelley Anderson. Held on the MTSU campus, this is a day camp for kids aged 12-18, but there the similarities to other camps end: This one’s a crash course on plugging in and rocking out. And it’s just for girls. The campers are provided everything from instrument instruction (even if they’ve never picked up a guitar before) to empowerment workshops, with the camp focusing less on musicianship and more on enabling young women to trust themselves and think independently.

Anderson, the 20-year-old president of the campus feminist organization Women 4 Women, is one of the few females in MTSU’s Recording Industry program who has chosen to focus specifically on technology and production. Increasingly conscious of the degree to which women are still relative outsiders in the worlds of rocking and recording, she got the idea for putting on the camp after hearing about a similar event in Portland, Ore., known simply as the Girls Rock ’n’ Roll Camp. Started by Misty McElroy in 2001, that event has grown tremendously in just two years, with a year-round after-school program, Girls Rock Institute, now in place.

Anderson, a trained guitarist and a member of the band Perfect World of Cranes, saved her earnings and traveled to Portland last summer to teach at the camp. As soon as she returned to Murfreesboro, she was determined to mount a similar project in her own town. She phoned friends, outlined the structure and started generating excitement about the idea. Her friends’ bands played benefit shows at the Red Rose Coffee House in Murfreesboro. With the aid of Dr. Carol Ann Baily, interim director of the June Anderson Women’s Center at MTSU, she procured the use of campus buildings and materials, which set the plan in motion. Weekly staff meetings were held to secure donated equipment and instruments and to discuss the camp in detail. With Anderson’s perseverance and the enthusiasm of all else involved, the Southern Girls Rock ’n’ Roll Camp was born.

“In math and science, girls have gone so far since the 1950s,” she observes. “You’d think in the music industry, the same thing would have happened.... I don’t think girls get involved early enough.” Indeed, when she started looking for volunteers to teach at the camp, she found a shortage of female musicians from which to choose. “If you don’t fit the pop star mold that the Nashville music industry has pumped out over and over, then you don’t have a place. Even in the independent music scene, you think there are definitely going to be more women—and there aren’t. The first couple of punk shows I went to, there were a lot of girls present, but they were at the shows, not onstage.”

With any luck, the Southern Girls Rock ’n’ Roll Camp will help change that: not just by teaching participants how to scream into a mic for maximum effect, and not just by teaching them how to bash out E chords on their Fender electric guitars. “I want them to have options,” Anderson says, when asked what she wants the girls to take away from the camp. “It’s for them to see new options about how they can be as a person.”

When it came time to staff her rock ’n’ roll camp, Anderson employed one of the most time-honored and effective methods in the music business: networking. She called up friends and invited other women musicians she’d met through gigging with Perfect World of Cranes. Nearly everyone was enthusiastic about the idea and agreed outright, with some of the volunteer instructors traveling from out of state.

One of those was Jennifer Strickland, a 21-year-old art major attending Truman State University in Kirksville, Mo. “I was in this band”—the now defunct Dumpster Divebomber—“and we played a show in Alabama, and [Kelley] just happened to be at the show. And she approached us after the show, because she really liked our band and wanted to record us.... So we came back and recorded in Murfreesboro, and that was when we really started talking about [the camp] and [how] she was really needing vocal instructors. And since I sang in a band, she thought that I would know how to do that, and so, yeah, I agreed. I told her I would definitely come.”

“I think it has been a great place for the instructors to network, especially the women who have been teaching,” Anderson explains. “They are like, ‘Oh my gosh, I see you all the time, but I didn’t know that you played drums.’ ” Networking is one of the core principles that Anderson aims to instill in the campers, though it should be noted that this is an entirely different thing from “schmoozing,” that most typical of music business interactions. The idea is not simply to make connections that can prove mutually beneficial, but to foster genuine bonds of kinship.

“The whole point of the camp is not so they can form this professional rock band and get up there and be awesome,” Anderson says. “It is just to get them excited about music and the whole community-building thing, so that they can meet each other—so that next fall when they go back to school and see some girl in their math class who was at the camp, they can be like, ‘I saw your band! The T-shirt you made was awesome!’ ” What’s more, in several years, when these same young women are touring in a band, making $3 a night, and their van breaks down, perhaps they can find help and a place to stay by calling up that girl they met in the Rock ’n’ Roll Camp’s button-making workshop. And then, when her band plays town, they can offer the same thing.

“It is so important to have women around other women, especially at this age when you are taught to look prettier and be competitive, instead of making music together and making a productive scene,” says Roby Newton of the Chicago post-punk band Milemarker. She flew down just for the event and conducted, along with Kelly Smith of the local band Glossary, a panel called “Girls on Tour.” Both women shared stories of club managers mistaking them for wardrobe personnel, if speaking with them at all.

“I think it’s hard for people to get used to you being the only girl in the band,” Smith says of her own experience in Glossary. “It’s hard for people to not see me as sort of the token girl. It is a little harder to get respect, I think, but if you believe in the band enough, that stuff doesn’t matter.”

The MTSU cafeteria is crowded with campers and staffers, along with students attending summer classes at the university, and without the laminated name tags, it would be difficult to tell the groups apart. Puddles of girls munch pizza and French fries as they go over lyrics on paper or jot down chord changes. There is none of the squealing or giggling or food fighting associated with throngs of adolescent girls, as they are too busy planning for Saturday’s big show, at which the bands formed during the weeklong camp will perform the song they’ve been rehearsing for the last five days.

The girls quickly finish their meals and hurry back for the afternoon workshops, although they’re never told explicitly that they must attend. Rather than heap excessive regulations on campers, the staff allows the campers to make the most of camp in the way they best see fit. And they do.

The McCoin triplets, 16-year-old Molly, Micki and Morgan, thought of forming a band in their hometown of Copper Springs, Kan., before they’d heard of the Southern Girls Rock ’n’ Roll Camp, but they had almost no instrumental know-how. Two of them, Molly (who now plays bass) and Morgan (guitar), have short, coppery, cropped hair and talk all over each other, finishing the other’s sentences hurriedly like multiple siblings are wont to do. Micki (drums), who looks nothing like her identical sisters, wears her hair long; she sits smiling, saying little.

“I thought it was going to be more like school, ya know? More structured,” Molly says. “Like, [I thought] they would have more authority, that they would try to tell us what to do, but it’s like, man, you can do whatever you want. Rules: That is why kids in school rebel.”

In the vocal instruction room, the mood is tense on this Wednesday afternoon. A dozen or so colorfully dressed girls sit sleepy-eyed or stand loosely in their places. Some listen to headphones, mouthing words to a song maybe only they know. A couple of the more boisterous singers in the classroom argue almost politely over who will perform the next song. Their faces and voices are slack and tired. Compared to Monday, the number of girls seems to have dwindled to about half—until the back door to the soundproof room flies open, and 10 or more girls all in black, save one, barge through and take over the CD player. These are the “screamers”—singers whose vocal style is over-the-top and in-your-face.

The all too familiar nü-metal strains of Linkin Park take over the room as the screamers line up in front of the singers in the class. Without a shred of irony or a hint of humility, these dozen girls sing word for word, with a frenzy rivaled only by rock’s greatest frontmen, “One Step Closer.” Heads bob, bodies jump and dance around, and by the end of the song, every last person in the room is shouting the refrain: “Shut up when I’m talking to you!” Song over, the energy remains; no one remembers whose turn was supposed to be next, and they don’t much care.

“It’s awesome meeting new people, and just singing and learning how to scream properly,” remarks Sambi Rain, a 15-year-old former Nashvillian who now resides in Pittsburgh. She’s the lead singer of Neo_Alpha 90, a five-piece screamo band formed at the first of the week—back when her hair was long. When she arrived at camp Monday, Rain’s hair reached the middle of her back, falling into a smooth, shiny sheet over her shoulders. Now it’s much shorter, maybe 4 inches long, and the new cut frees up a stunning, smiling face.

“I’d thought about cutting it before, but now seemed the right time,” she explains. She lets a hand fly through the wispy new cut and declares it, officially, “fun.”

Which seems to be the overwhelming theme of the camp. It isn’t so much the forced fun found at other camps for kids, where there are name games and silly songs. In fact, staffers tried rallying the girls to cheer in sections on the first day, an activity the campers roundly rejected, seemingly to the counselors’ delight. Fun for these kids means sitting on the floor gathered around a tape machine, learning the ins and outs of recording.

In the live sound workshop, a group of three stares intently, nodding as their instructor explains the mysterious knobs and slides of a four-track recorder. The girls have only just seen the machine for the first time today, and after correcting their instructor—“You didn’t check the master fader”—they plug in and start recording. Unclear of exactly what to play, they improvise a short tune that can be best described as noise rock. As they listen to the playback, they share the headphones, with no single girl ever keeping them too long.

“This is kind of good,” declares Molly Thomas, a precocious 15-year-old Hume-Fogg freshman who prattles eloquently for someone nervous about entering high school. At the moment, she’s listening quietly and purposefully, smiling to the strange beat of the song, never looking embarrassed or proclaiming it crap. There’s none of the self-consciousness you’d expect from an eager teen hearing her first-ever effort at multitrack recording.

It’s hard not to imagine that the all-girl environment makes a huge difference on the campers’ comfort level. They seem not to notice the absence of guys, but when prompted, they admit that being around the opposite gender tends to make them act differently. “Most girls get relegated to a minor role in rock ’n’ roll bands,” explains MTSU women’s center director Baily. “They may have had music at school, but unless they want to toot a horn in marching band, where there are no electric guitars, there are few options. Girls need instruction in an environment where they can reach their potential, without guys, who normally dominate the rock scene, saying ‘You can’t do it.’ ”

“I really don’t think about guys a whole lot,” Sambi Rains says. “I am more of a music person. But,” she admits, “some girls tend to be embarrassed or self-conscious when they are around guys, so maybe it would be a lot harder for them to stand up in front of a crowd.... Like, if it’s co-ed, maybe the girls don’t want to be aggressive, or they are afraid of what the guys will think.”

Freed up not to feel shy or sheepish, these girls demonstrate remarkable dedication and focus all week long, not to mention an admirable willingness to share, collaborate and create. There’s an electricity in the air, the sort of snap a place gets when it’s filled with people actively making art and having a blast doing it.

Appropriately enough, the Southern Girls Rock ’n’ Roll Camp closes with a grand finale, a concert in the Wright Music Hall at which family, friends and fellow campers get to witness the fruits of the past week’s labors. It’s pretty much like any school concert: The hallway swells with beaming, pleased parents and pumped-up children. But there’s also clearly something different going on here. One anxious mother checks her watch and smoothes the hair from her face. She bears a hanger of stage clothes in one hand, her daughter’s shoes in the other. But rather than toe shoes or a sparkly leotard, she’s holding a ripped mesh shirt and duct-taped combat boots.

“I never thought my daughter would be playing a Ramones song,” one father remarks proudly to another. The men check the batteries on their camcorders and compare notes on concerts they’ve seen.

“It takes a special kind of parent to encourage someone, especially a young daughter, to attend a rock ’n’ roll camp,” Anderson remarks. “It is almost, in a sense, encouraging rebellion. It is redirecting rebellion into a constructive avenue where they can talk about it in fanzines. Or they can do music journalism or they can express it in their art or music, but not in negative ways, against something healthy like education or their parents.”

This positive spirit is evident on this Saturday evening. The girls’ faces are exaggerated with dark eyeliner and glitter, squeals emanating from their brightly painted mouths. They shout to their mothers and wave, giving their fathers big hugs before darting backstage. One of the bassists jokes about crowd-surfing to her mother during her set.

Toddlers squawk and grandparents secure their hearing aids as the lights go down and the first band takes the stage. The Fates, a six-piece, jump-start the show with a rousing version of The Ramones’ “Beat on the Brat.” Though most of these girls have only been playing together for a week, each band takes the stage fearlessly. Lyrics are forgotten and mishaps occur, but the momentum of the show never slows.

At one point, feedback pierces the auditorium as Jamina Abegg plugs her guitar into an amp, and a stagehand switches the guitar’s sound down. Her band, the Lap Children, launch into an original song, “The Real Thing,” before Abegg has time to discover that her instrument can’t be heard at all. But she doesn’t freak, she doesn’t stop, she doesn’t run offstage. She merely drops her guitar and screams into the mic. Hazel Rigby, the Lap Children’s bassist, her face painted with an anarchy symbol, tears through the song and smashes the neck of the bass against her head. Drummer Maggie Jones stands up on her stool at song’s end, furiously beating her kit and kicking down the cymbals. The girls wield their instruments wildly and finish by flopping around on the stage floor. The audience eats it up.

At the end of the night, a few of the instructors bang out a punked-up version of Billy Idol’s “Dancing With Myself,” and before long the place resembles a scene from a John Hughes movie. The entire staff and all 70 of the campers start doing cartwheels, flipping and hopping in front of the stage. Some girls dive onstage and begin moshing and conga-lining around the band. Arms are flailing, feet are flying, and it looks like the most fun anyone’s ever had.

After the show ends, the girls stand in the lobby chatting, prolonging their revelry and goodbyes. Sweaty and soaring, they exchange e-mail addresses and cell numbers and promises. There is much talk of the camp next year.

Two girls trade hugs and one yells goodbye. She stops short of the door. “See you later,” she says. “Not goodbye, it’s see you later.” Then she throws up her arm, her first and pinky fingers extended, and tells her new friend, “Keep rocking.”