With his floppy hat, long beard and dangling earring, "Hippie" Jack Stoddart could be dismissed as an anachronism—a holdout from the Whole Earth movement clinging to bygone traditions. But that would be a mistake. "Hippie" Jack is a character, all right, but he also has character. It's on display in the black-and-white photographs that depict the lives of the Tennessee hill people who have been his friends and neighbors for the last three decades.

Those photographs make up a remarkable new exhibit at the Tennessee State Museum, a visual record of the life he chose some 36 years ago. In 1973, Stoddart and his wife Lynne bought 48 acres on Highland Mountain in Crawford, Tenn. A mere $7,500 secured the land, the barn and the cabin where they began their new life in Overton County. While the Stoddarts were happy to leave behind the rising crime rates in their home of Miami, there was more to the move than just a change of scenery.

"I'd studied the practices and processes I wanted to explore, but I never really had a subject," Stoddart explains on a recent afternoon walk-through peppered with self-deprecating witticisms, tall tales and remembrances. "We wanted to document this vanishing culture."

The result, ultimately, was Renaissance Jack: The Work of Jack Stoddart—Hippies, Hill People & Other Southern Marvels. The exhibit includes nearly four decades of Stoddart's photography, all silver-gelatin prints developed from 35mm negatives. Eschewing larger-format cameras and extensive lighting has enabled Stoddart to capture his images with spontaneity. Consequently, his low-key approach no doubt puts the subjects of his candid portraits at ease.

The photographs introduce the friends, neighbors, shopkeepers, farmers, moonshiners and musicians Stoddart has known throughout his decades on the mountain. In "The Girls," Stoddart captures a giggling group of young Mennonite girls, their smiles beaming beneath their bonnets. The subject of "Uncle Hack" ran a beer joint on Highland Mountain, while "Claude Ramsey" is described by Stoddart as "a living museum" who taught him all about global warming way back in 1972.

"He was way ahead of Al," Stoddart deadpans.

In "Hermit Shack," Stoddart captures the exterior of Ramsey's home in the early '70's. Looking closely, one can discern a washbasin outside his back door and a number of hand tools leaning against the side of the house. The image is much sharper than a tintype from the Civil War, but the scene itself is largely unchanged.

Mainstream America was exposed to the culture of contemporary hill people in the 1960s through images in Time and Life magazines. While Stoddart is a fan of the images themselves, he's quick to damn what he sees as a patronization that is built into the voyeuristic nature of such projects.

"I feel these people were given short shrift," he explains. "[The projects'] approach to the whole culture was condescending."

Photos throughout the exhibit demonstrate the Stoddarts' complete immersion in the culture. In one image, a shirtless Hippie Jack labors on his farm; an entire block of the exhibit is dedicated to poignant portraits of Stoddart's children growing up in the country.

Their lives revolved around campfires, grassy meadows and an entire menagerie of animals that seem as much a part of the family as the siblings themselves. If not for the kids' contemporary clothing, the pictures could be 100 years old.

This timeless quality haunts Stoddart's work. He makes a conscious effort to keep objects like telephone poles and electric lines out of his images (which he admits is easy to do on Highland Mountain). One room of the exhibit is dedicated to photographs of the region's Mennonite communities. With his subjects clad in traditional dresses, bonnets and hats, the images truly do seem to hold the encroaching century at bay.

The exhibit also includes images of Nashville, a smattering of hand-tinted prints, and portraits of musicians such as John Hartford and Bill Monroe. Hippie Jack's connections to Tennessee's music scene led to his creation of Jammin' at Hippie Jack's, a festival-based live music program produced in his barn and at the Tennessee State Museum's Buffalo Bill Stage. The syndicated show is carried on 115 public television stations, including NPT-Channel 8, and the exhibit features several monitors displaying performances from the series, among them John Cowan and the late, great Tim Krekel.

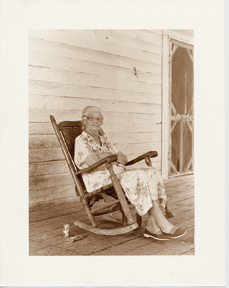

Maybe that sounds ambitious, not to mention modern, for someone scrupulously devoted to a less accelerated life. But Stoddart sees his subjects as individuals, not outsider-art collectibles. In "The Porch," an older woman rocks in a chair on her front porch. Both rolling tobacco and dipping snuff sit expectantly next to her chair on the otherwise unoccupied stoop. The wooden siding on her house runs parallel to the long porch slats, pointing toward a screen door with a tasteful, decorative frame. Stoddart describes the whole scene in detail, summing it up with a statement about the "symmetry of simple living."

From the woman's amused expression, it seems likely that watching the world go by was one of the highlights of her day. Perhaps this aspect of hill culture leads some to mistake "simple living" for passivity, or ignorance. But in our contemporary urban experience—an ADD assault of downloadable, economic-fear-based, partisan-pleasure-driven point-of-purchase distractions—a wealth of attention to the present moment might do us all a world of good. Maybe Hippie Jack Stoddart and his subjects are the ones forging a new model of 21st century life, and we are the ones out of time.

Email arts@nashvillescene.com.