I’m pretty sure I’ve seen all the Hellraiser films. But truth be told — as with similar hostages of the Dimension Films/Weinstein Company direct-to-video factory of the ’90s and early Aughts like Children of the Corn and The Prophecy — it can be hard to be sure. Dimension Films had a habit of taking a horror spec script that it owned, then having someone write in The Hell Priest (don’t call them Pinhead — at least, not to their face) and some assorted Cenobites and creating a fairly mercenary sequel.

Despite this Mad Libs approach to much of the later years of the franchise, there were occasional moments of awe or a viscerally memorable kill. Or at least the one where Hell is the internet or a LARP event or something where Henry Cavill shows the groceries (that would be 2005’s Hellraiser: Hellworld, from Barb Wire director Rick Bota). Without those haphazard years, we might never have gotten Scott Derrickson’s ascension to A-list horror (and Marvel) director. But as far as truly transformational, singular horror, nothing has topped the first two films in the series.

In the age of reboots, remakes and streaming, they’ve been trying to get Hellraiser sorted out for quite some time. Lots of directors and concepts have come and gone, with David Bruckner (The Night House, The Ritual) eventually emerging from the The Hills, The Cities pile of directors to actually make the film. The end result, premiering Friday on Hulu, is genuinely fascinating. It doesn’t supersede the original duo, but it is focused on amplifying (and tweaking) the cosmology of creator Clive Barker’s theologians of the gash in a way that no one who tried between 1990 and last year could make stick. So despite some misgivings, respect is due the filmmakers for really digging deep into what we know of the mysterious puzzle boxes and the portals that they unlock into human depravity and experience.

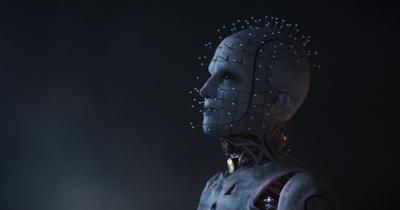

Jamie Clayton (Sense8) is the new Hell Priest, and she is spectacular. She’s got pearlescent pins in her face and she presides over the mayhem in this new installment. She resonates much as her predecessor Doug Bradley did in the majority of the previous films. We have a similar refresh done on the Chatterer Cenobite, and the rest of this version’s sex demons are all brand-new and creatively fashioned. My personal favorites are The Weeper (whose limbs do the splits) and The Masque (a most upsetting riff on Doctor Who’s Lady Cassandra O’Brien.Δ17), but I like the general approach to these malicious assistants quite a bit.

We learn some new things about the iconic puzzle box — its shape (and nomenclature) evolves, depending on how many victims it has claimed in its current cycle, whether by its striking hook or by the machinations of others. This is actually the most shocking change in mythology from previous entries, as our extradimensional hierophants were always more interested in the desires that brought them into our realm, not the hands of whoever opened it. Well, no more. Now, the box claims all sorts of innocent bystanders, which is a choice that defiantly asserts the Americanness of the new Hellraiser’s ideology (despite being shot in Serbia). Here’s my analogy, in keeping with Hellraiser ’22’s use of addiction as foundation: The old box was the guest list, the new box is a crack pipe.

Our protagonist Riley (Odessa A’Zion) is a recovering addict with a history of questionable choices, so she tests the nature of the audience’s empathetic response; she frustrates viewers looking for a traditional Final Girl. Riley gets caught up in this messy supernatural situation (How messy? Lots of splatter, nonconsensual surgical modification and testing the limits of what the body can endure) and then spends her all trying to atone, resolve and reverse the grand unholiness that’s been going on for millennia. We spend most of the film in her shoes, gradually building out of hard-won respect rather than simply embracing tropes from the beginning.

Real talk: Most Hellraiser sequels are just terrible — or worse, indifferent — placeholder narratives that exist not for an audience but to hold onto the rights. So just by virtue of its ambition and metaphorical realignment, this new film leaps far ahead of the majority of the franchise. But it feels different in ways that are hard to articulate, like there’s a philosophical shift in what’s going on here that the filmmakers feel like keeping close to their chest. Don’t get me wrong, I’m already psyched for a sequel and where this new strain of Barker’s mad genius is bound for. But Bruckner’s film is working a different kind of spell than the 1987 original or its exquisite 1988 sequel, and it’s going to require another viewing to try and reconcile them all. But there is great joy to be found in actual effort being put into the Hellraiser series again, and let’s view this as a promising first step toward a new kind of unspeakable.