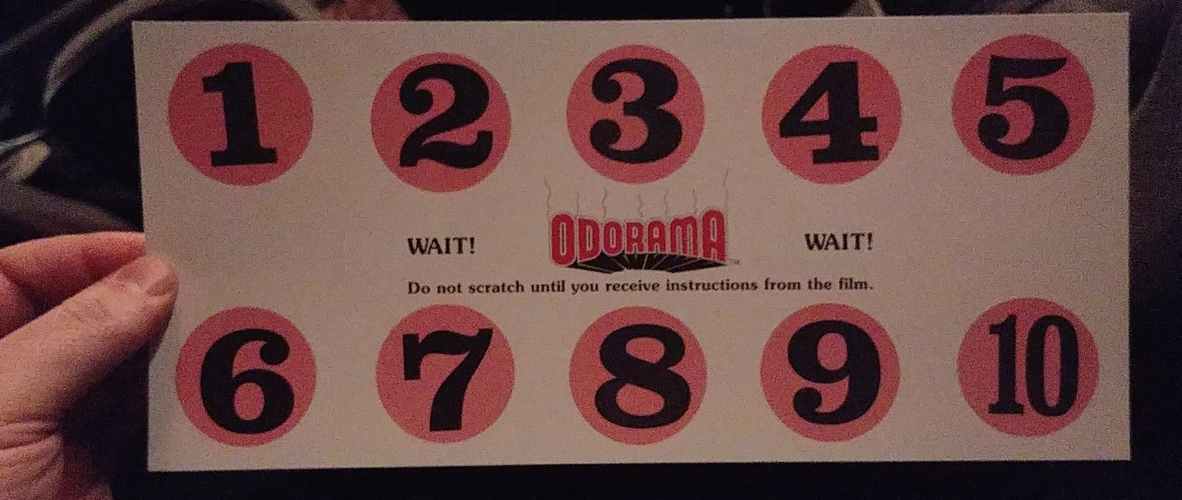

The Odorama scratch card for 'Polyester'

Due to a family death and a collapse in the wiring of my car, it wasn’t until very late Friday night that I made it to Knoxville for the latest incarnation of the Big Ears festival. I tell you this up front so you understand that I approached all the film and music this remarkable gathering had to offer in a state of emotional exhaustion and deep, spiritual searching. And it did me a world of good. I spent more time with the film section because that’s my thing, but I also saw several utterly incredible musical performances. If nothing else, the hit to miss ratio at Big Ears is untouchable. Nothing was bad, and everything had emotional resonance.

Filmmaker/critic/genius Blake Willams had programmed an entire section on Saturday devoted to 3-D cinema called Stereo Visions. Though I hated missing the screening of Williams' own film Prototype on Thursday, it will be showing at the Nashville Film Festival in May. Williams’ Stereo Visions program was superb, kicking off Saturday with a capacity crowd for Jean-Luc Godard’s 2014 masterwork Goodbye to Language. It had been a few years since I had seen it, so you can imagine my surprise when I realized how funny it was, and how revolutionary it still was with some of its 3-D aesthetic. There may be no more adventurous moment in the past decade than when Godard separates the two linked stereoscopic images, panning the right field while the left remains still.

The program showing afterward, Stretch Fold, was a quartet of 3-D shorts, each using the technology in different ways (including one, "2012," which utilized a process called Pulfrich 3-D that creates vortical dimensionality from horizontal movement — you can explore Pulfrich 3-D via YouTube and several internet tutorials, which you should). My personal fave, "Insight’s Cataract," involved a series of outdoor tableaux that, via multiple exposures, seemed to be oscillating and collapsing in on themselves in both time and space.

Before Slacker, Richard Linklater made his first feature, It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow by Reading Books. It’s a shaggy tale of cross-country travel, a tone-poem to dudes who drift, and a loose statement of objective for pretty much the whole rest of his career. It’s also a great train movie. You could feel the joy in the audience when Daniel Johnston popped up, and you can sense what themes were going to drive the engine of Linklater’s body of work. It’s very interesting to see that Linklater has always had a gift for photographing bodies, even and especially when his own is the subject. Everybody Wants Some!! is not quite so anomalous. It's Impossible was a fun and revelatory way to start The Public Cinema’s program of fundamental works of regional independent cinema, A Sense of Place, which all of the rest of the films I took in were part of.

If you haven’t seen John Waters’ Polyester, then I just have to feel sad for you. It's the first of the two films Waters made in the ’80s that marked his shift toward the mainstream, and it’s a tribute to Douglas Sirk, Rainer Werner Fassbinder and William Castle, with heaving bosoms, romantic betrayal, suburban ennui — and a killer gimmick, being filmed in "Odorama," with a matching scratch and sniff card keyed by onscreen signals. It’s always fascinating to see a Waters film with a crowd these days, because you can never be 100 percent sure as to how everything is going to go over. But there is nothing quite as magical as seeing a packed house taking the journey of scratching on that card even though they know something horrifying awaits. Also, lots of people know Divine, because Divine is immortal and an American icon, but a lot of folks have never seen an Edith Massey performance on the big screen, and there is just no way not to be won over by her guileless joy. The highest compliment I can pay any contemporary auteur is that it feels like Bruno Dumont has been looking for Edith Massey his whole life. And I hope he finds her, in some capacity.

The most amazing thing about Big Ears audiences is that they’ll take a chance on anything. It was deeply heartening to see the variety of folks that would show up for shows, regardless of accessibility or genre. This is also one of the problems with Big Ears audiences, because the Whitman’s Sampler approach to offerings can be an issue — or at least it was during Diamanda Galás’ performance at the Tennessee Theatre. This was a bucket list performance, especially as Galás rarely performs in the U.S. outside of Chicago, New York and San Diego. Her performances are like operatic recitals mixed with exorcisms, her voice flowing from a deep and heavy whisper to a resonating shriek and back again. She finds the common links between R&B standards, apocryphal gospel, country-blues and sacred texts, and reshapes the tonal canvas with the visceral unearthliness of a religious vision bordering on psychosis.

For me, it was like being in church — but also a Dionysian church, because they were a lot of people who I wouldn’t have minded seeing torn to shreds in a display of sparagmos. It’s part of the problem of Galás performing in, dare I say it, a casual context. Because it wasn’t for everyone, and that realization led to a lot of distracting exits from the theater. Also, and this is just a general concert-going axiom to live by: If you're thinking about using the flash on your phone's camera during a live performance, DON'T. In spite of those factors, Galás was electrifying. I wept profusely, and her first encore, an understated and rapturously beautiful take on Johnny Paycheck’s “Pardon Me, I’ve Got Someone To Kill,” may be the most transcendent experience I’ve had in the entire state of Tennessee. After her show, the skies let loose, and folks slipping out onto the now-wet streets had to figure out who they really were.

From there, it was ten or so blocks through the rain — dazed, elated, evolved, and transformed — to meet up with some friends from the Nashville contingent. In the words of the Donna Louise postcards, “a disco whispered … ‘perhaps tonight?’,” and you could follow the clarion call of 4/4 programmed boom-boom echoing through the darkness to The Mill & Mine. Kelly Lee Owens was killing it. Her beats were superb, her audiovisual game was on point and she would hit the crowd with perfectly tweaked Roland acid sounds that made the majority of asses shake and also made the endorphin-producing parts of the brain work overtime, delivering an adaptive dance party that called to mind Adamski’s legendary Liveandirect album. I had only heard of Owens in passing beforehand, but know that she needs to be held in the highest esteem of anyone interested in electronic music as an art form, or in dance music as an awesome thing to do.

Shortly after Owens' set finished, Four Tet took the stage, and my friends went nuts. Four Tet worked in an idiom that in my many decades has been called slambient, lounge-house and brunchcore, working with a lot of interesting sounds and moods. With the exception of one heavily-arpeggiated major key movement just after 1 a.m. (“that’s a deep cut from Rounds,” they told me afterward, leaving me to future research), it felt like he was exploring the more chilled-out realm of dancefloor abandon — which is cool, because the audience was feeling it, recognizing loops and breaks and giving in to the rhythm. It was a good way to return to the realm of the real, after the Galás-Owens one-two punch of visceral sublimity.

Sunday began with The Beaver Trilogy, an astonishing meta-work about American culture consisting of three short films. The first is a documentary made in 1979 about a Beaver, Utah, impressionist who specializes in Barry Manilow and Olivia Newton-John; the second, a black-and-white fictionalization of the first, made in 1981 and starring Sean Penn just before his breakthrough into mainstream consciousness; and a third iteration, shot on film in 1985 with Crispin Glover and E.G. Daily, that diverges further from the initial documentary and yet digs much deeper emotionally.

All three pivot on a local talent show in which the subject performs an unqualifiable rendition of Olivia Newton-John’s yacht-disco throwdown “Please Don’t Keep Me Waiting,” and all three explore the idea of fame, authorial exploitation, sexual identity and social freedom. Taken as a whole, The Beaver Trilogy is a journey that covers just about every emotion you can imagine, and it asks very interesting questions about gender, performance, and identity that are still quite relevant today. It’s staggering to see Penn wield his charisma, even then unable to be hidden, cut with such perceptible self-doubt. And Glover is superb, eliciting sincere empathy and deep frustration from the audience and the rest of the cast. Between this and Gas Food Lodging, there’s a doctoral thesis to be written about portrayals of Olivia Newton-John in indie cinema.

Rostam

Rostam’s 1p.m. show at The Standard, which he described as "sexy brunch," was a revelation. His first solo album, last year’s Half Light, is a great soundscape of textures and some killer songs, but live — with a string quartet and a drummer/tech module operator backing him up- everything became a delicate swirl, eclipsing the studio takes and seeping into the spine of the listener. Rostam has an exquisite voice, equally soothing and sweeping, and I’d love to get him, Jónsi and Joel Gibb together to form Queer Dream-Pop Voltron, maybe with help from Sufjan Stevens, and save the world with a kind and insightful sonic sweep.

His set was like spending the day in bed at amorous pursuits, but with an aquarium in the corner of the room so that the outside world was represented, making the intimacy of lovers and the choice to focus on interior discourse all the more meaningful. He played a new song that, as far as stately portraits of skinny-dipping go, may one-up R.E.M.’s “Nightswimming,” which is not a comparison I make in a cavalier fashion. Closing with a quietly reverent cover of Nick Drake’s “Pink Moon,” he sent us back out into the world. The sun may have been out, but emotionally, it was a boozy swoon through a sultry evening.

Slipping back into the film section, I finished my festival weekend with Property, a 1979 indie out of Portland, Ore., about a group of bohemian friends, lovers, and acquaintances (including Walt Curtis, the poet whose work led to Gus Van Sant’s debut Mala Noche) trying to raise the $200,000 to buy the city block that holds their houses. Say what you will about rotary phones and public cigarette smoking, but nothing makes a viewer confront the passage of time quite like focusing on money. In the intervening four decades, people haven’t changed much, but that economic Habitrail that constrains us all has gotten smaller, crueler and so exponentially more expensive that it never stops being shocking. Writer-director Penny Allen only made one other feature before moving to France, but Property is a remarkable film, and one that anyone interested in independent cinema of the ’70s should check out (see Allen's website for an on-demand streaming option).

A glimpse of Knoxville's architectural aesthetic

Knoxville as a city has a layout that is conducive to the festival experience. I can’t begin to tell you how convenient the whole experience was. It is right and appropriate for Nashville to be horribly jealous of what Big Ears manages to accomplish, because the lineup is great and the curation is superb. But it’s not a competition, because there is no way Nashville could do something like this — the city is just physically not set up for it. So in my mind, it’s not a fight. And I don’t wanna fight. I’m just glad for the experience, and that as fucked up as so much of our state is (and I can say that as a lifelong Tennessean), Tennessee does do right by Walt Whitman, containing multitudes.