Country music’s outlaw movement has been mythologized, valorized and criticized time and time again. An essential artifact and document of that scene and sound is filmmaker James Szalapski’s long-inaccessible documentary Heartworn Highways, a film with as much of a devoted cult as the music itself. Most of the more canonized names are just a whisper on the wind here — you won’t find Willie, Waylon or Merle in the doc, nor the faces of the recently departed Jerry Jeff Walker and Billy Joe Shaver. But that allows for a perhaps more honest and authentic depiction of a musical movement, examining not from the top down but from the true underground of the time. Unavailable or only accessible in low quality for many years, this country music landmark has been restored by Kino Lorber, alongside a soundtrack reissue by Light in the Attic Records.

Part concert movie, part behind-the-scenes and backstage documentary, Heartworn Highways is something distinctive, more like a compilation album than a conventional doc. It follows a certain tendency and mentality across vastly different sectors of the country-Western spectrum, from the songwriter sound that emerged in intimate clubs like Nashville’s Exit/In and Austin’s Continental Club and Armadillo World Headquarters, in steep opposition to the industry machine of the time, all the way up to the electrified Southern rock of recently deceased fiddler and right-wing conspiracy theorist Charlie Daniels. There’s an almost rambling, unnarrated quality to Szalapski’s direction — it can at times make the film a little difficult if you’re not already familiar with the figures involved, though the musical performances are undeniably impressive. But it’s that fly-on-the-wall quality that makes Heartworn Highways feel so spiritually aligned with the subculture it captures; it’s shaggy and rambling, like a hard-drinking and hard-living songwriter or an unfinished gravel road.

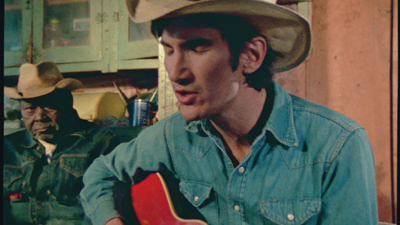

The legends shown here are a dime a dozen, and many before they had even really begun to fully bloom. We see Steve Earle when he was just a shaggy-haired kid jamming at a kitchen table, not yet the musical activist, actor and father of equally legendary and tragically late Justin Townes Earle; we hang with Rodney Crowell as a fresh-faced young guy in an oversized graphic T. Guy Clark sings a handful of his masterpieces, like “L.A. Freeway” and “Texas Cookin’,” brings us into his home, talks us through guitar care and instrument repair. The moments with Townes Van Zandt are particularly tender, both for his goofy, aw-shucks screen presence and for the real ache you can feel from his personal reflections and performance of “Waiting Around to Die.”

When we first meet David Allan Coe, he’s at the helm of his own tour bus, a fitting introduction for a larger-than-life figure who has claimed, at various points, to have lived in a hearse upon first moving to Nashville and hidden out in a cave while avoiding the IRS in the 1980s. Eventually the bus arrives at Nashville’s Tennessee State Prison (closed in 1992 due to overcrowding) for a poignant and climactic performance for the true-blue country raconteur. Coe essentially grew up in the carceral system, spending two decades on and off in various institutions. As the colorful singer explicitly discusses how his time in a juvenile facility drove him toward crime, Szalapski zooms in on the side-eyeing scowls of the armed guards only a few feet away.

The self-styled “original Mysterious Rhinestone Cowboy” is something of a strange sight in the cold steel facility, jumping around in sparkly disco-ball boots doing a prog jam with his drugged-out band. The crowd becomes much more actively engaged during DAC’s stage banter, as he tells jokes about sniffing typewriter fluid and attempted prison breakouts in an affect that feels uncannily reminiscent of Richard Pryor. As opposed to the almost tent-revivalist intensity of Johnny Cash’s prison concerts, the air around David Allan Coe is strangely silent and sucked-out, almost dead, even though the audience clearly relates and responds positively to his own accounts of years behind bars. There’s maybe the feeling that DAC could go too far at any time, that he might speak too harshly or truthfully to incarcerated experience, that he might rile the men up and provide justification for cruelty from the guards. When he first arrives at the penitentiary, DAC immediately speaks to the issue of overcrowding, of tensions that arise between mixing different generations of convicts, and almost demands some kind of structural change at the facility if he’s going to play.

Though his legitimate art and achievements may have long been overshadowed by the series of racist and all-around offensive novelty songs he infamously and regrettably released on the underground trucker market in the 1980s, the force of nature known as DAC released an incredible, often deeply beautiful body of more respectable — if still transgressive — country work throughout the ’70s and ’80s. He wrote some of the most beautiful songs I’ve ever heard, like “Would You Lay With Me (In a Field of Stone),” and sometimes even espoused radically progressive views. In one body, he brings together the absolute best and worst of country music, and there’s maybe no better figure to truly embody the tensions and complications of the outlaw era.

These men were and are effortless poets of ordinary experience, illicit exuberance, and existential pain, but they were still men, insightful but not infallible, often crude or cruel to women. It’s that set of contradictions that Heartworn Highways captures so insightfully; it pierces through the myth of what Waylon would later call the “Outlaw Bit,” examining an era of innovation with unvarnished authenticity, keeping its distance just enough as not to turn real people into icons on a pillar.