“You’d be surprised at what music can do,” says Rip Patton. He would know. Patton was among the civil rights activists who desegregated Nashville lunch counters and movie theaters in the 1960s. He rode across the South on buses as a Freedom Rider, sitting beside his white and black peers while mobs of segregationists awaited their arrival at depots and terminals.

“There’s an old saying that music can soothe the savage beast,” Patton says. “One of the things about music is that we all can’t talk at the same time, but we can all sing at the same time. And so we used music to comfort us, to give us strength. To know that we were all under the same banner. That we were all together.”

Patton’s group of Freedom Riders left Nashville on May 19, 1961, just days after a bus filled with riders associated with the Congress of Racial Equality was bombed in Anniston, Ala., and another bus was met by a violent white mob in Birmingham, Ala. Many in the Nashville group wrote out their last will and testament before they boarded the bus.

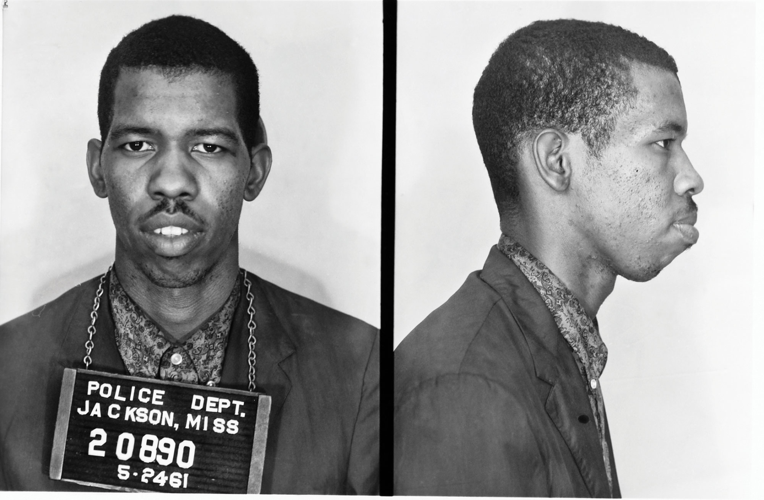

Rip Patton’s 1961 mug shot

Music was at the core of their mission. This week, a confluence of Nashville artists will celebrate the vision and courage of seven local Freedom Riders — Patton, Allen Cason, Etta Rae Simpson, Frederick Leonard, Mary Jean Smith, Joy Leonard and Patricia Armstrong — with song.

The central theme of the program is “I wonder …” according to Margaret Campbelle-Holman, the founder and artistic director of local nonprofit Choral Arts Link. “As a child … as events occured in the civil rights movement, I would watch the TV and wonder who those people were,” says Campbelle-Holman. “How did they get there, what did they do to be able to be there and deal with what they were dealing with?”

Choral Arts Link provides choral training and leadership opportunities for Nashville youth in grades 2 through 12. Holman has partnered with the contemporary music ensemble Intersection for the past four years in an annual program called Upon These Shoulders. This year’s concert — which will take place at Fisk University Chapel at 7 p.m. Saturday, Feb. 15 — is titled From the Back of the Bus. The MET Singers, the signature group of Choral Arts Link, will perform the Negro spiritual “I Want Jesus to Walk With Me,” as well as songs by Nashville poet Melissa Smith and Metro Nashville Public Schools veteran music teacher Nita Modley Smith.

Kelly Corcoran, the artistic director of Intersection, says her ensemble aims to disrupt the notion that the faces of classical music are all white male European composers. “The composers that are creating classical music are diverse, and black composers are a really central, important part of that narrative,” says Corcoran.

The ensemble will play music composed by Florence Price, who in 1933 became the first black woman to have a piece of music performed by a major orchestra. Much of Price’s work was thought lost — until 2009, when a collection of manuscripts was discovered in her summer home. “It’s kind of an interesting thing right now to figure out,” says Corcoran. “What is going to be her legacy? How is her music going to live beyond her life?” Intersection will also perform songs from Nkeiru Okoye’s opera Harriet Tubman: When I Crossed That Line to Freedom. Corcoran hopes to acknowledge Tubman’s role in the early stages of the women’s suffrage movement.

In building the program, Campbelle-Holman spent time with Patton to help translate the lessons of the movement to her young chorus. She says she hopes the program will plant a seed in the minds of young people that will somewhere down the road compel them to be active in their communities. More than anything, she believes in the power of song.

“When you’re singing,” says Campbelle-Holman, “that sound and vibration starts inside yourself. When you’re sharing that with someone else within the choral, you’re actually sharing inner vibrations with others, and when they are in unison, you’ve made harmony. … If a child doesn’t know what harmony feels like or looks like or sounds like, how can they identify it when there’s confusion in the rest of their lives?”

The freedom songs sung by Patton and his peers were sometimes derived from gospel music, church hymns and Negro spirituals. Other times, the songs were made up on the spot to accomodate a situation. In the summer of 1961 at the notorious Mississippi State Penitentiary, also known as Parchman Farm, Patton and his fellow Freedom Riders — among them John Lewis, James Bevel, C.T. Vivian and James Lawson — sang constantly. The prison guards threatened to take away the activists’ mattresses if they kept it up.

“And so they would open the doors, and we would throw the mattresses out in the hall,” says Patton. “We had a song for that.”

And then he sings: “Ain’t gonna let no mattress turn me ’round. Turn me ’round. Turn me ’round. Ain’t gonna let no mattress turn me ’round. I’m going to keep on a-walkin’, keep on a-talkin’, marchin’ up to freedom land.”

Patton’s voice is low and clear. The simple song becomes, remarkably, both a hymn and an anthem. Listening to him sing, it’s easy to imagine him as a very young man, boarding a bus in Nashville, ready for whatever lay ahead.

From the Back of the Bus is rooted in Campbelle-Holman’s vision of building a bridge between the activism of the civil rights movement and activism today. “There are two tenets I learned from Rip Patton,” says Campbelle-Holman. “[The movement] had to be intergenerational. It had to be interracial. We’re trying to create a discussion — intergenerational, interracial — specifically [between activists] then and activists of now.”

Along with project supervisor Teree Campbelle McCormick, theater director Jon Royal has created the connective tissue of the event, tying together the performances of Choral Arts Link and Intersection with a loose narrative about Price, Tubman and Nashville civil rights leader Diane Nash. Actor Alicia Haymer will perform all three parts in what should be a compelling presentation. “There’s lots of struggle and lots of symbolism, but lots of joy, too,” says McCormick.

Additionally, Royal and McCormick have created a community-engagement component that will lead up to From the Back of the Bus. Funded by a Metro Arts Commission THRIVE award, the Ride Along With the Freedom Riders events are panel discussions featuring Freedom Riders and contemporary local activists. The second of these will take place at 6:30 p.m. Thursday, Feb. 13, at First Baptist Church, Capitol Hill — a site of the students’ nonviolence training. The discussions will be about what it took for the Freedom Riders to have the training, courage, faith and “sheer nerve” to accomplish what they did, McCormick says.

Campbelle-Holman says the performance’s title, From the Back of the Bus, refers to the places where injustice still occurs. “We can all play a part in making things better,” she says, “and that’s what the crux of this is about.”