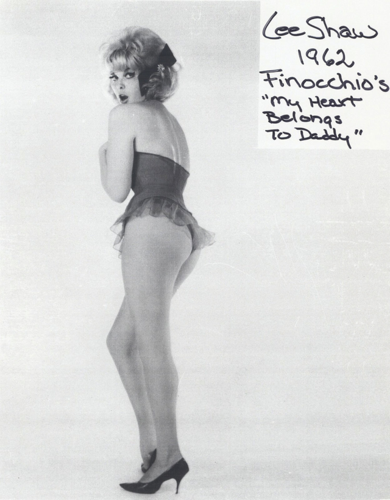

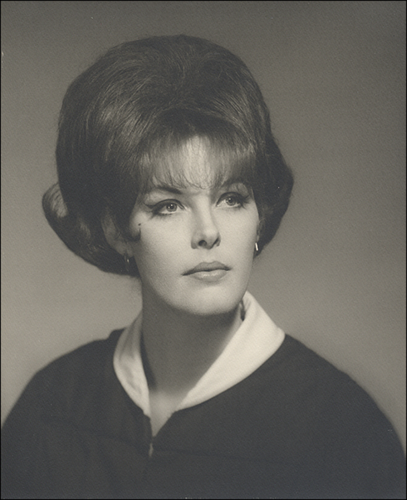

Aleshia Brevard in A Secret Only God KnowsBrooks Fund History Project

"From my earliest years, I’d known that something was wrong with me,” writes Hartsville, Tenn., native Aleshia Brevard in her 2001 memoir The Woman I Was Not Born to Be: A Transexual Journey. “It wasn’t about my body. That wasn’t it at all. It was about who I was, about the boy I was presumed to be. I’d been subjected to all the traditional male training and none of it took.”

Brevard, who died last year at age 79 due to pulmonary fibrosis, recalls the experience of having gender-reassignment surgery in 1962.

“I was one of a mere handful undergoing transexual surgery in America,” Brevard writes. “The procedure was in its infancy, but I was prepared to take advantage of everything medical science knew about altering gender. I hoped it knew enough.”

Aleshia Brevard

Coming out as a trans woman was a brave move at the time, though it is of course still a courageous move now — according to LGBT-rights lobbying group Human Rights Campaign, 2017 saw the most fatal crimes ever recorded against trans people. In 1962, there wasn’t much data on what happened to transgender people post-reassignment surgery. In order to even schedule a surgery, Brevard had to meet with a psychiatrist — who, she writes, had no idea what to even ask her.

Brevard writes that throughout consultations and appointments for her procedure, she often had to endure rude or abusive comments from doctors and nurses — like when a doctor told her she would do well in life because she already knew what it was like to be a man. She wondered aloud what the hell the doctor meant by that — she never knew what it felt like to be a man.

Aleshia Brevard

“Only a male could possibly believe that,” Brevard writes. “I had no concept of what it was like to be a man. Why did this doctor think I needed gender-altering services?”

Brevard was one of two Middle Tennessee trans women interviewed for for the Brooks Fund History Project’s documentary A Secret Only God Knows, which premiered on Nashville Public Television in 2015.

The Brooks Fund History Project, which is put together by the nonprofit Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee, is an ongoing endeavor to collect oral histories of LGBT people in the area. Archived in the Nashville Public Library’s Special Collections, the Brooks project is meant to give voice to people who weren’t able to talk about their experiences as openly as they might be able to today. Brevard had a full and rich life — she was a Playboy Bunny, had parts in movies, played Trudy in an off-Broadway rendition of Steel Magnolias, and was a professor at East Tennessee State for a stint in the ’90s.

The Brooks project began in 2009, when Deidre Duker and Phil Bell interviewed LGBT people who lived in the Middle Tennessee area before 1970, focusing on how they were viewed and how they experienced their own communities. Duker also directed A Secret Only God Knows.

“Gay and lesbian citizens of Middle Tennessee have a lot to tell us about what life was like for them 50 or 60 years ago,” says Iris Buhl, volunteer chair of the Brooks Fund History Project. “They were — and are — an integral part of the fabric of this community. Our knowledge of the history of Middle Tennessee is incomplete without their stories.”

In the documentary, Brevard says that at the time of her surgery, LGBT people didn’t talk a whole lot about their experiences. Brevard moved from Hartsville, which is about an hour northeast of Nashville, to San Francisco before she turned 20. She wanted to escape an environment that largely ignored LGBT people, and sometimes considered them dangerous. She says she was unsure that anybody in Hartsville had ever considered gender issues.

“I think my dad was very worried about me, and I think perhaps that’s understandable,” Brevard says in A Secret Only God Knows. “They certainly didn’t know anything about transexuality or [transgender people].”

Brevard’s father sent her off to play with other little boys to try to push her more toward masculine activities, and she says during that time she suffered abuse at the hands of other children. Many involved in the documentary and oral histories spoke of violence committed against them as young people.

Aleshia Brevard

As part of the documentary, the project interviewed 26 people: 11 gay men, five lesbians, two trans women, a few straight observers (to get a sense of how straight people experienced the LGBT community then) and three same-sex couples. Most of the LGBT interviewees were in or around their 70s when the interviews were conducted.

“The biggest revelation was how much courage it took for most of our interviewees to talk to us,” says Buhl. “The old fears are still very deeply ingrained in so many of them, even if they are leading relatively open lives now. As a result, each story is very special, and each person a hero.”

Brevard opens her memoir’s first chapter with a story about her mother telling her the world would be boring if everyone was the same. She writes that she couldn’t help but think her mom didn’t know what she was talking about — that there could be nothing better than being like everybody else. Brevard writes that over the years, she learned that it was fine to be different, but that her flair and eccentricities had nothing to do with her gender.

“I feel like transexual was something I was,” Brevard says in A Secret Only God Knows. “It was like going through puberty, I suppose. We all transition, and I transitioned. I know there is a lot of discussion both in the community and outside about all of our labels and how we self-identify. I think of myself as just a woman. I went to [get my surgery] on July 7, 1962, and that’s when I began living. In my estimation, that’s when I was born.”