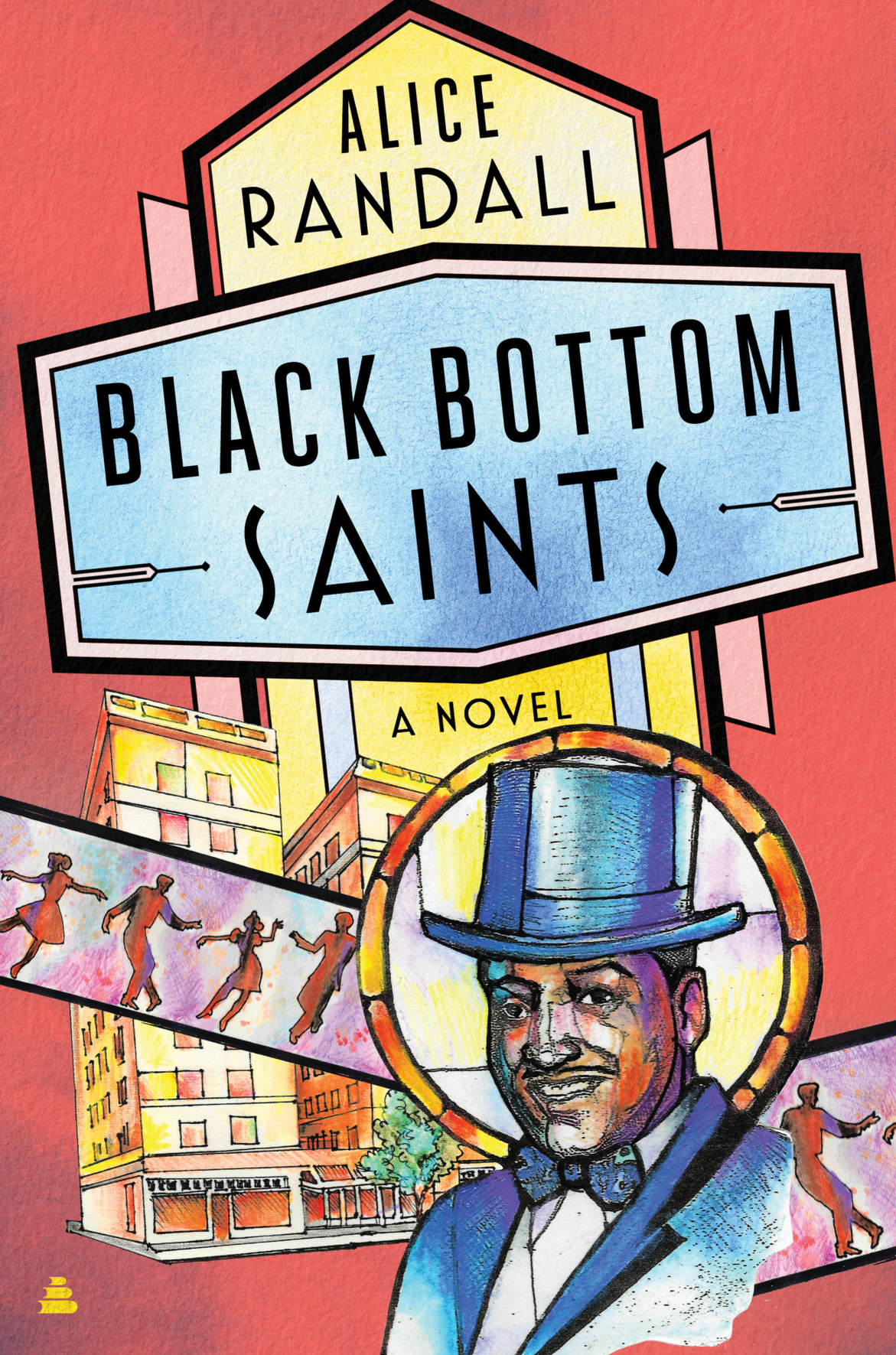

Alice Randall’s fifth novel, Black Bottom Saints, is the fictional last will and testament of a real-life Motor City culture maven. Joseph “Ziggy” Johnson emceed at storied show clubs, wrote a gossip column for the Michigan Chronicle and founded a beloved school of dance for Detroit’s Black daughters.

In the novel, it’s 1968, and from his deathbed, Ziggy composes paeans to his “saints.” Inspired by Catholic lives-of-the-saints books, Ziggy’s manuscript highlights artists, entrepreneurs, educators and strivers who hailed from Detroit, performed there or loved the place — who “suffered so much, and so differently, but who had each found a way, or made a way, to experience radical joy.”

Outside the walls of Black-owned Kirwood Hospital, his shining adopted city is also expiring, “dynamited to pieces in the name of urban renewal, singed in the embers of righteous rebellion.” Ziggy’s gilded-era Detroit goes by various aliases: Black Camelot, Motown, the “largest and most important city in Alabama.” And then there’s “Black Bottom,” the name of a once-thriving, now-razed African American community on Detroit’s East Side, so called for the dark loam where early settlers planted farms. But to Ziggy, the name evokes more than map boundaries or demographics. He defines its essence with a quote from Lew Massey, his Patron Saint of Lawyers and Fixers: “Black Bottom ain’t a place. Black Bottom an attitude. A Detroit attitude.”

Ziggy describes that attitude, born of the Great Migration and new wealth seeded by the thousands of factory workers he calls the “breadwinners,” whose wages supported all-Black businesses, hospitals, private schools, a booming lake resort called Idlewild and a vibrant live music scene. The breadwinners’ expanding prosperity and stylish swagger lifted up a generation:

In Black Bottom, charm and squalor, nature and industry, opportunity and obstacles, citified and country-time, got all shook up into a strong cocktail that made a person believe they could do what they wanted to do, they could be who they wanted to be.

That confidence cocktail produced Randall herself, a Detroit native who attended the real-life Ziggy Johnson’s dance school for five years. (Her mother left for Washington, D.C., with her when Randall was in grade school, but the threads back to Detroit, her father and Ziggy held firm.) Ziggy’s articles, read aloud to her by her dad, seeded Randall’s writing aspirations, as she explained in an interview with Marcus Whitney on his YouTube channel in February.

More crucial still were Ziggy’s lessons, which went far beyond ballet or tap. In the highly anticipated spectacles he mounted every Father’s Day, his girl-pupils danced with (and for) luminaries like The Four Tops and The Supremes and learned to perform elegance and self-possession until they owned those traits outright. Ziggy’s in-class storytelling of the lives of his saints, who had risen from humble and sometimes tragic roots, offered the girls a stealth education in how their forebears transformed grief into music and poetry, movement and action — how “a body can bear articulate and soul-elevating witness.” That’s the inheritance that both the real and the fictional Ziggy hoped to bequeath: inspirational morality tales, lessons in resilience through self-invention and a series of roadmaps for the breadwinners’ children that would guide them from the auto plants to any theater of operations they chose.

This novel is also Randall’s articulate and soul-elevating witness, a song of gratitude to the man whose “citizenship school” gave her the tools to channel her own suffering into the radical joy of writing. And in an inspired creative twist, Randall writes a proxy of herself into the narrative: “Colored Girl” (C.G.), a former Ziggy protégée whose aloof and abusive mother spirited her away to D.C. as a child, has been entrusted with the task of finishing his manuscript. C.G.’s biography seeps into Ziggy’s saints’ book in the form of a parallel third-person narrative — set apart in italics as a prelude to each saint’s chapter — chronicling her coming of age and her discovery and curation of this nearly lost fictional manuscript. It’s an initially confusing device that unfolds slowly to reveal a deeper layer of story.

Of course, the real-life Randall gave herself this assignment. She spent years poring through Ziggy’s columns and Black newspaper archives and interviewing witnesses to the boomtown years of Black Bottom in order to compile these 52 mini-biographies, one for each week of the year. This feels, to me, like the book Randall’s whole life has prepared her to write, her own origin story folded into an elegiac, literary time capsule of the Detroit That Was — a cultural artifact that might one day serve as a blueprint for that lost world’s reinvention.

To read an extended version of this review — and more local book coverage — please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.