In 1912, Pablo Picasso pasted a fragment of oilcloth onto a small oval-shaped still life. In 1979, The Sugarhill Gang spliced interpolations of disco hits into rap songs. The Frist Art Museum’s Multiplicity: Blackness in Contemporary American Collage draws a line straight through those two points and into the rich artistic tradition where it extends — collage and collage-informed art made by some of the most influential and relevant artists working today.

“This is the first major museum exhibition devoted to the subject, which I would argue is really understudied and undervalued,” says Frist senior curator Katie Delmez. Delmez has selected roughly 80 works of art made by 52 artists whose ages range from 30 to 80 for the expansive exhibition, which will span the Frist’s Ingram Gallery. Masterworks by long-celebrated powerhouses like Kerry James Marshall and Howardena Pindell will share space with pinups overlaid with celestial maps by Lorna Simpson, a salon-style installation of 21 junglescapes peopled with hip-hop luminaries by Lester Julian Merriweather, and digital amalgamations of Black visual culture from Lauren Halsey. Multiplicity is a wide-ranging, multifaceted feat, and its significance should not be understated.

“The notion of collage is very rooted in the African American experience,” Multiplicity artist Derek Fordjour tells me from his studio in the South Bronx. “It’s a way of putting old and new things together, or finding new life for old objects or old materials.”

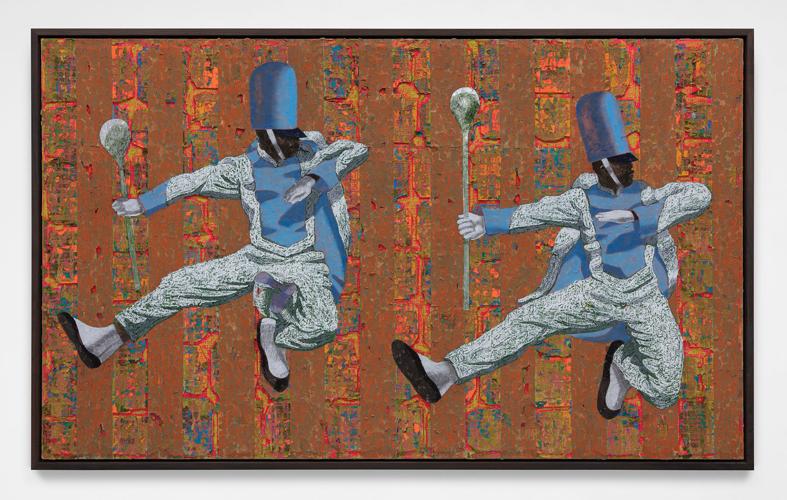

Fordjour is a native Memphian who has recently exhibited at both the St. Louis Museum of Art and The Drawing Center, and his art-making practice involves building up and scraping off layers of paint, pastels and charcoal into something that resembles the surface of an old billboard. Onto those rough terrains he composes figures that are, in many ways, superhuman. His work “Airborne Double,” a 60-by-100-inch mixed-media work from 2022, depicts a pair of leaping drum majors in matching marching-band garb, seemingly suspended in midair.

“I really try to imbue the DNA of my work in contemporaneous notions of the Black figure, the Black entertainer, the Black athlete,” he says. “But I want to weave in an undercurrent of discomfort, in the case of ‘Airborne Double,’ this notion of flying, which is kind of superhuman. And, you know, for me, that is a double-edged sword — that it can be very flattering to reference athleticism, to the extent that it transcends one’s own humanness, but I’ve also seen that kind of superhuman quality used against a Black person in the court system, when you have a cop saying, ‘I was afraid for my life, the guy was so fast.’”

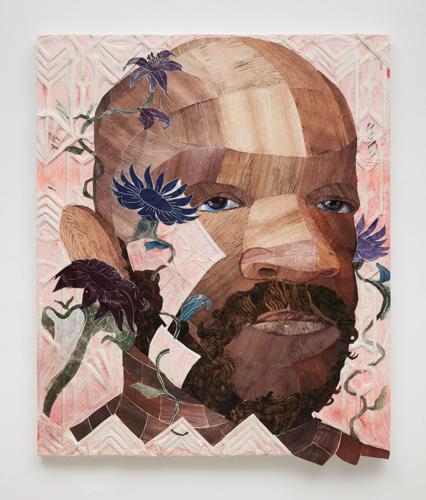

“Uncle Scott,” Yashua Klos. Woodblock prints on archival paper, Japanese rice paper, acrylic, spray paint, colored pencil and wood mounted on canvas; 72 x 60 in. Collection of Marc Rockford and Carrie Gish, courtesy of the artist and Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York.

Another Multiplicity artist with a studio in the South Bronx is Yashua Klos, who has two works in the exhibition — “Uncle Scott” from 2022 and “The Face on Mars” from 2009. Klos, who was raised on Chicago’s South Side, has a singular technique that incorporates woodblock prints instead of ready-made source material.

“I’m carving blocks of wood,” he says, “carving into the surface of them in low relief, then rolling ink out over the surface, putting paper on top and then, with hand pressure, pulling prints from those blocks of wood. Those prints then become the source material that are cut up and recombined to form the imagery.”

The result is an unexpected mix of color and texture that gives Klos’ work a timeless quality. The portrait of his uncle recalls the cubist still lifes of Georges Braque, who pasted trompe l’oeil wood-grain wallpaper onto charcoal drawings at the same time Picasso was making the aforementioned “Still Life With Chair Caning.” But with Klos’ contemporary, autobiographical subject matter, “Uncle Scott” is also a testament to artistic determination.

“I think there’s always been this resourcefulness around African American cultural production,” Klos says. “I’ve always seen a collage attitude in that. Hip-hop is a great example — with sampling, taking bits of a preexisting work of musical arrangement and slowing it down, or remixing it, or chopping it up and making a whole new genre of music. It’s a very clear example of that resourcefulness in the present day.”

It was a similar kind of resourcefulness that led Multiplicity artist Jamea Richmond-Edwards to collage. The Detroit native and longtime art educator was formally trained as an oil painter, but she began making collages because she had a newborn baby, and was concerned that the oil-paint solvents and mediums wouldn’t be properly ventilated in her home studio.

“I just naturally transitioned into mixed-media,” Richmond-Edwards tells me from her studio in Maryland. “I recently started describing it as almost like scrying. Like cultivating a garden and just giving it what it needs.”

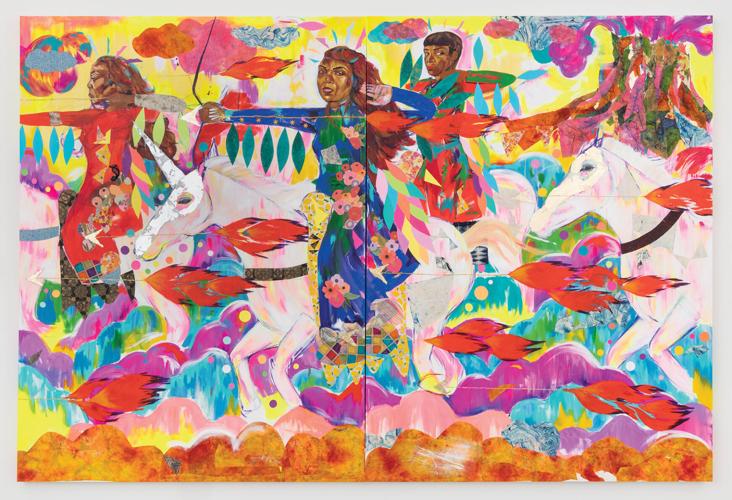

Richmond-Edwards works with a fantastical palette full of brilliant colors that evoke Yo! MTV Raps, Fraggle Rock and Lisa Frank school supplies — all favorites from her childhood. Her massive “Holy Wars,” from 2022, is an example of the scale that artists can work with in collage — at 96 by 144 inches, it reads like the kinds of classical history paintings Richmond-Edwards might have taught her students about. The artist depicts herself astride a white unicorn, galloping along a terrain of pink, yellow and blue cotton-candy clouds as flaming arrows whiz past and a volcano erupts hot-pink puffs behind her.

“This was my response to what really feels like spiritual warfare that’s going on,” she says. “So what I decided to do with it is to make myself a victor in it, because at one point, I felt like a victim. It’s really allegorical to the adversity and uncertainty that we are inflicted with currently living in this particular time.”

Memphis-based artist Brittney Boyd Bullock’s “No It Ain’t, Yes It Is,” is both of this particular time — it was made in 2023 — and rooted in history. Bullock collages monoprints of black-and-white newsprint photographs depicting Black figures onto a canary-yellow panel. Each of the figures has been photographed from behind, and each is looking off into the distance. What they’re looking toward remains ambiguous.

In a conversation from 2020 featured in the book Black Futures, artist Arthur Jafa discusses the theme of Black genius, which is central to his 2016 masterpiece “Love Is the Message. The Message Is Death,” the only work of video art featured in Multiplicity. “There’s something to be said about [the] ability to be able to see beauty everywhere,” he says. “It’s something that Black people have developed. We’ve actually learned how to not just imbue moments with joy but to see beauty in places where beauty doesn’t necessarily exist.”

Fordjour recounts an early discovery of the kind of beauty Jafa describes. “One of the sources I collected many years ago was a postcard from Emancipation Day,” Fordjour explains. “It was a painting of recently freed slaves. ... All they owned was what was on their bodies, but the clothes that they wore were stitched together from many different sources. The idea that they were sort of collaging together this new identity from the beginning — that previously an owned person that had no autonomy and now the, you know, potential to fashion your own self in terms of how you dress — it just sent my mind down so many rich paths around how deep and how far this goes, this sort of pulling together disparate resources to try and add up to something dignified.”

“Pulling together disparate resources” could be Multiplicity’s subtitle. Fordjour calls it “collage logic,” and it extends into the programming around the exhibition as well. The exhibition catalog includes artist biographies that were written by Fisk University students. Vanderbilt University is partnering with the National Museum of African American Music to host Multiplicity artist and Knoxville native Wardell Milan as an artist-in-residence. Fordjour will be working on public art projects on the Tennessee State University campus. Tinney Contemporary will host an exhibition of work by Multiplicity artist Lovie Olivia, and Fisk University’s Carl Van Vechten Gallery will host a show of collages from its collection by 20th-century giants Romare Bearden, David Driskell and Sam Middleton. Plus, a daylong celebration of Multiplicity will take place at the Frist on Saturday, Sept. 23, featuring panel discussions with artists from the exhibition — including Richmond-Edwards, Olivia and Ewing, as well as Nyugen E. Smith, Paul Anthony Smith, Rashaad Newsome and more. And there are even more collaborative events that will be announced in coming weeks — visit fristartmuseum.org to keep up.

“I felt like it was important to meet people where they are, and to let the impact of the show spread beyond the walls of the museum,” Delmez says.

Once you start looking at things through the lens of collage logic, it’s hard to stop seeing examples of it everywhere — quilts made from discarded scraps, multicolored signs piling up along graffiti-covered storefronts, gumbo made from bits of well-seasoned seafood. And, of course, multigenerational exhibitions that bring all those big ideas together.

From the Frist’s ‘Multiplicity’ to concerts, theater, films and more, here are the most promising events of the season