Dystopian visions of resistance and rage — this is often where imagining the future leads us, to worsening versions of our present fears. But artists working within Indigenous futurism can see things differently, like Choctaw artist Benjy Russell. With fishing line, flowers, mirrors and light, in photography, gardening and sculpture, he divines queer utopias. Floral arrangements appear like altars in the night, and a forest gleams with sparkles.

“I feel a sense of joy and hope in the future,” Russell tells the Scene. “When given present-day circumstances, there’s not a lot of joy to be found.” He creates his art from the perspective of a future where all these problems have been solved.

“The ideas of gender and sexuality labels are something for now because it’s something we’ve had, and I feel like rage is definitely for now. But building toward queer utopia, you have to realize that we’re going to be past a lot of that, hopefully.”

In rural DeKalb County, Russell has an idyllic cabin and a stretch of land where his riotous, rhapsodic garden is the subject and setting for his art, as well as backdrop for the portraiture he provides pro bono to queer sex workers. His yard is a quarter-acre of flowers that he planted after his husband Sterling died, the seeds mixed with his ashes. From 2021 to 2022, Russell invited people to visit his garden installation A Cowboy Riding a Beam of Light, for which he printed and hung 15 of his photographs on enormous pieces of fabric. In the near future, he will host a residency for LGBTQ artists on the property, called the Sterling Residency.

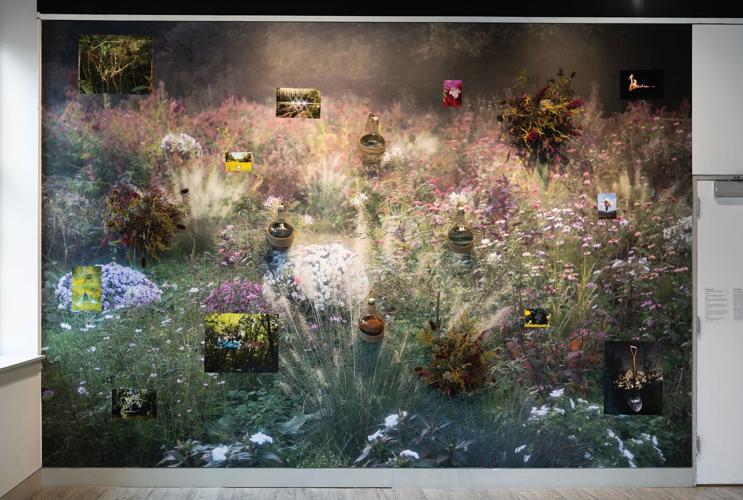

'A Cowboy Riding a Beam of Light,' Benjy Russell

A self-described redneck, Russell has lived in rural Tennessee for 16 years, but he’s originally from Oklahoma. He grew up on the Chickasaw Nation reservation “in a very conservative, very small, one-stoplight town.” As an artist, he is well-practiced in keeping his emotions close to the surface, and his generous honesty is best met in kind.

“I have to experience every single emotion, every single experience that I possibly can to its fullest extent, so that when I make work, I am able to talk about it with the language that I need, whether that’s the emotional language or the visual language,” he says. “Your job as an artist is to experience every emotion possible so you can use it whenever you have to.”

To create such a sense of magic, Russell uses a lighting technique similar to what was used to illuminate Hollywood stars in the 1950s and ’60s. “I started to think about the filters that get used in photographs as a layer of reality that you’re removing,” he says. “Adding a soft focus or stacking a star filter removes the overall image a little more from reality. People think my work is Photoshopped or digital collage, because the lighting on the subject doesn’t match the lighting of the environment. I think that really messes with the brain and how people perceive things.”

Russell currently has a piece included in Horizon Scanning, a group show at the Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington outside Washington, D.C., which will run through the presidential inauguration. The work, titled “This Is How the Garden Grows,” is a massive photographic backdrop of his garden, with dried floral arrangements from the gardens of sex workers, as well as four glass vitrines containing elements of earth, air, fire and water. The fire vessel contains burnt copies of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the U.S. military budget for 2024 and the annual bill for Russell’s HIV medications, totaling nearly $90,000.

“It’s basically a spell,” he says. “Once they told me [the work] was going to be in Washington, D.C., during the election, I was less concerned about being able to show my art there and more concerned with being able to cast a spell on the town while the election was going on.”

In May, Russell will have his first solo show in a gallery in more than a decade. Hosted by Tinney Contemporary, Dark Big Bang finds the artist engaging deeply and directly with his family’s history. “A couple of years ago there was a really intense falling-out that I had with my biological family, and then also some of my queer chosen family,” he explains. “It was pretty devastating. I was also researching a lot on quantum theory at the time. The Dark Big Bang is the leading theory in quantum physics on the origin of dark matter in the universe. It became very apparent that there was a parallel between how dark matter was released into the universe and how it affects our reality, and how root traumas happen and how they affect our existence as well.

He continues: “The work is seeking to unpack root traumas that I’ve experienced — familial, queer family, my family coming from Choctaw land in Alabama, being forced to walk the Trail of Tears, our land allotment that we were given and then immediately had to sell off, my grandmother and her sibling going to Indian boarding schools, how that affected my father’s side of the family, how they interact with each other — and using that to give empathy and space for others to heal.”

For Dark Big Bang, Russell is building structures out of materials like reflective glass beads used on interstates, colored gel tubes found in club lighting, and a composition of wood shavings and mycelium. All of these pieces will reference and deconstruct traditional Choctaw basket weaving, embroidery and pottery designs. And thanks to a Current Art Fund grant he received from the Andy Warhol Foundation, “everything’s not going to be held together by duct tape,” he says with a laugh.

“Most [Indigenous stories] are taught as historical. All of our culture is something that ‘used to be,’ as seen in films or old black-and-white tintypes,” he says. “The idea of taking the culture and the ancestors into the future and showing that [this is what] is going to happen is so beautiful, so hopeful and uplifting.”

Photographing this year’s NAIA Pow Wow and discussing Nashville’s future with members of the Indigenous community