George Saunders

I don’t recall exactly how I first discovered George Saunders’ work. I was teaching contemporary American lit, focusing on short stories, and I’m pretty sure I stumbled upon his In Persuasion Nation in the library stacks. Reading those first stories was like jumping into very cold water — bracing, invigorating, somehow fun despite the odd and unexpected assault of the writing. And there was something else, too. Beneath the wit and the biting observations, beneath even the inimitable capital-V Voice, was a quiet insistence, begging you to hear it: Pay attention, now. This is important.

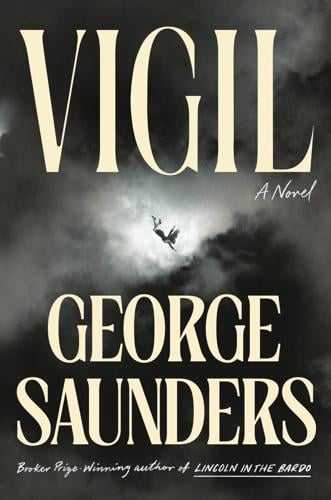

After winning the 2017 Booker Prize for his wildly inventive and thoroughly humane Lincoln in the Bardo, Saunders was catapulted into a new stratosphere of attention, and with the massive success of his Substack Story Club, he has become a kind of guide for all kinds of searching souls. Introducing him as the recipient of the National Book Foundation’s 2025 Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, host Jeff Hiller called him “the ultimate teacher of kindness and of craft.” So perhaps it will come as no surprise that his latest novel, Vigil, raises nuanced questions about both.

There’s a brute simplicity to Vigil, but it’s a simplicity that needles and provokes, which means it’s not simple at all. Like Lincoln in the Bardo, Vigil occupies itself with death and the otherworldly figures that accompany that transition, but in this version, the chorus of ghosts is reduced to two main spirits: the novel’s narrator — Jill “Doll” Blaine, who died in the 1970s — and a ghost she calls the Frenchman, an otherwise unnamed man from an earlier era who claims responsibility for inventing the engine.

Jill has arrived at the deathbed of K.J. Boone, CEO of an oil company and well-known climate change denier. Jill’s job, as she sees it, is to comfort the dying as they pass from this world into the next. Like the traditional figure of a psychopomp, she does not judge, feeling for her charges an “old, familiar, generalized fondness” for the person “who had not willed himself into this world and was now being taken out of it by force.” The Frenchman, on the other hand, does not hold so objective a view of this dying man, insisting with firm clarity that “he is no good” and urging Jill “to lead the CEO, as quickly as possible, to contrition, shame, and self-loathing.”

Though these two are the primary parties in the death experience of Boone, they are joined at times by other spirits, including two of Boone’s work colleagues in life, both named Mel. To avoid confusion, the Mels go by their last initials, “R.” and “G.” These two reinforce the dying man’s internal insistence that he has done nothing wrong: “Doesn’t every idea, said R., even those judged by some standards to be fallacious or those which have been disproven outright, deserve to be honored with the public’s attention?”

Saunders is not, you might note, subtle.

Except that he is. And therein lies the beautiful and maddening complexity of his work. It is crude but seductive. It is absurd without sacrificing any measure of gravity. It is lively and amusing and deadly serious (pun fully intended).

A conversation between George Saunders and Ann Patchett tops our list of this season’s best book events

As Jill struggles to suppress the memories of her former life and focus on the work of “elevation” before her, and as Boone’s daughter struggles to reconcile her good, kind, loving father with the sure knowledge of his deep and consequential failures, any one-dimensional version of his life and death — or any person’s life and death — becomes untenable. Justice is not always served. People are not always held accountable for their actions. People do not so easily forgo their own view of themselves as fundamentally good and loved and worthy of that love.

And maybe, the book seems to be arguing, they shouldn’t have to. In the moments after Boone’s death, the Frenchman confronts Jill with a question: “Tell me, do you believe it? Really believe it? Bad and good are the same? Damage does no harm?” She doesn’t offer an easy answer but ends where she began, with a kind of clarity: “I felt a familiar, powerful truth being beamed into me by a vast, beneficent God, in the form of this unyielding directive: Comfort. Comfort, for all else is futility.”

Perhaps that’s a kind of answer after all.

For more local book coverage, please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.