Environmental observers popularized the term “sacrifice zone” in recent decades to describe the geographic death wrought by industrialization. Land, soil, ecosystems, habitats and neighborhoods withered slowly, by leaching chemicals and sea level rise, or quickly, by behemoth hurricanes and coal ash tides spilling across backyards.

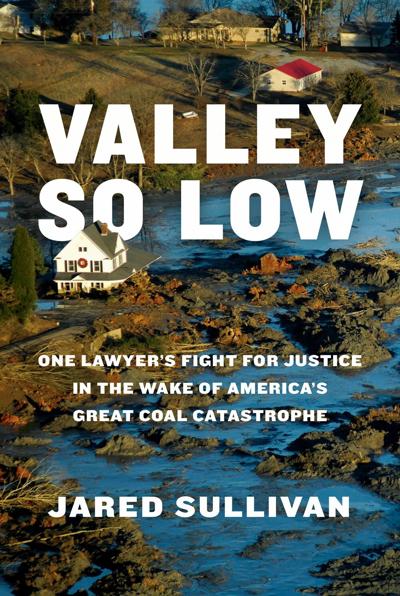

Jared Sullivan’s Valley So Low begins with the moments in December 2008 when TVA’s Kingston Fossil Plant spilled a billion gallons of coal ash slurry — the toxic sludge of heavy metals, water and mineral byproduct spewed from the plant's constant power generation — into the surrounding valley on the banks of the Clinch River outside Knoxville. The tragedy itself ranks among the nation’s most destructive industrial disasters.

Sullivan focuses on the extended and painful drama that follows a nasty and complicated spill: Who gets dirty, who stays clean, and the twin flames of responsibility and blame.

His 200-odd pages stand as a formidable act of reporting. Sullivan, a magazine writer based in Franklin, shines with his empathetic effort to humanize the blue collar workers drawn to decent pay and stable work who, having trusted their employers at TVA and cleanup subcontractor Jacobs Engineering, unwittingly walk the long trail of avoidable suffering toward their premature deaths.

While dismissive authorities from TVA and Jacobs (who frequently avoid direct exposure themselves) downplay the health risks posed by coal ash, workers Ansol Clark, Mike McCarthy and Jeff Brewer go home caked in it after 14- and 16-hour shifts. Sullivan meticulously reconstructs their lives at the job site, a daily churn of moving the toxic sludge from one place to another, and at home, where the substance’s disturbing health effects extend to family members. Their lives soon link up with Jim Scott, an underdog plaintiffs’ lawyer who squares off with arrogant TVA legal adversaries with elite pedigrees and carries most of the book for Sullivan.

In a book full of winding details, Sullivan — no doubt deeply moved by the hours of interviews with Scott and others — underestimates how quickly readers get onboard. He frequently belabors and repeats rich biographical descriptions, sapping his own strength and pulling attention from the book’s core drama: the David-and-Goliath fight between guilty and defensive institutions, including a public agency chartered by the American people, and the workers they sacrificed out of fear, greed and negligence.

Beyond his archival contribution to an important moment in Tennessee and environmental history, Sullivan drives home the book’s moral lesson on most every page, the cold-hearted betrayal of an employee by his employer. Even in the throes of sharp physical deterioration, despite being denied basic protective equipment, Sullivan reports how his central characters kept showing up to the job site for a day’s work, compelled by a solid paycheck and the vanishing belief that TVA, and Jacobs, wouldn’t knowingly pay them to die.

Oct. 26-27 in downtown Nashville, the festival will celebrate literary excellence close to home