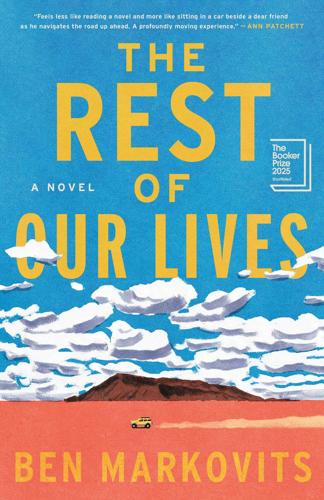

Tom Layward, the hero of Ben Markovits’ novel The Rest of Our Lives, is at a crossroads. The younger of his two children is leaving for college at Carnegie Mellon, a seven-hour drive from their home in New York, so the time has come for Tom to make good on a pledge he made 12 years earlier when he learned that his wife Amy had an affair: “When Miriam goes to college, you can leave, too.” But does Tom have the gumption to go through with it?

When Amy decides not to make the trip to Pittsburgh to drop off their daughter, Tom recognizes an opportunity: Rather than return home and confront his wife about their marriage, he can keep driving west. With this brilliantly simple conceit, Markovits launches his hero on a midlife odyssey, a cross-country road trip that enables Tom to reckon with his life’s emotional balance sheet and chart a path for the future.

Narrating his own journey, Tom makes for an entertaining travel companion, reflective but never maudlin. A veteran of domestic squabbles, he knows his crisis is neither unique nor particularly poignant; he knows equally that no one else can solve his problems for him. His complaints ring with a tone of the universal. “Nobody tells you what an intense experience loneliness is, how it has a lot of variations,” he says.

The Rest of Our Lives, short-listed for the Man Booker Prize, is a novel of earned wisdom, with a self-aware protagonist who shares observations on a wide range of topics, from family politics — on mediating between wife and daughter, “At some level everything you feel or think is a kind of taking sides” — to the deterioration of Friends over its 10 seasons (“People turning into caricatures, but maybe this is what happens to people”).

Most often, Tom finds himself wondering how his life has reached this cul-de-sac, when what he really wants is to roam freely. He fantasizes about writing a book about pickup basketball in America, but it sounds like a pipe dream. Tom has a tendency to suffer in silence, surrendering to inertia. It’s a propensity that becomes troubling when he fails to find a medical solution for the face bloating and eye excretions he suffers every morning. At work as a law professor, he has been asked to take a sabbatical after students complained about his class on hate crimes. He doesn’t know if he’ll be asked to return, or if he wants to go back.

Ben Markovitz

The material may sound downbeat, but in Markovits’ hands it remains lively and engaging. Tom’s route, Midwest to the Rocky Mountains and finally to his son Michael in Los Angeles, takes him on a This Is Your Life tour of friends and family that offers clues regarding the forces that shaped his personality and fate. His first stop is with a colleague from his grad school years — a scholar who has carved out a university career, whereas Tom remained a dilettante. “I didn’t want to write about other people’s experiences or ideas of the world,” he confesses. “I just wanted to sit around and read books for the rest of my life.”

Tom finds spiritual company among his middle-aged brethren, his own ennui a specific version of a widespread malaise. His brother Eric in South Bend, Ind., is separated from his wife and lives in a two-bedroom apartment, seeing his children only on Wednesday nights and weekends. Tom thinks Eric is a “momma’s boy” whose problems originate in his being “someone who didn’t understand what it takes to get by in a world that isn’t filled with people who love you.”

The novel’s humor is pitch-perfect throughout, starting with the protagonist’s surname — Layward, a neologism that makes him sound like an amateur wanderer. Self-deprecating to a fault, Tom never takes himself too seriously. He declares early that any “illusions” you have about a spouse after two decades of marriage are entirely “your fault,” because staying married means “you’ve accepted that this is what they’re like, and what your life with them is like, and you stop expecting them to do or give you things you know perfectly well they’re unlikely ever to give you. It’s like being a Knicks fan.”

As Tom drifts farther from home, he summons remembrance of his early years with Amy, who he initially felt was too beautiful and refined to be in his league but has become “this person with such complicated resentments and dependencies directed at me. I don’t think I was worth it.” Tom’s problem is not, as some claim, his lack of passion — “You don’t really care about anything,” an old girlfriend says — but the mystery of how to rebuild a life. To find a way forward, he may have to reassemble pieces of his past.

For more local book coverage, please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.