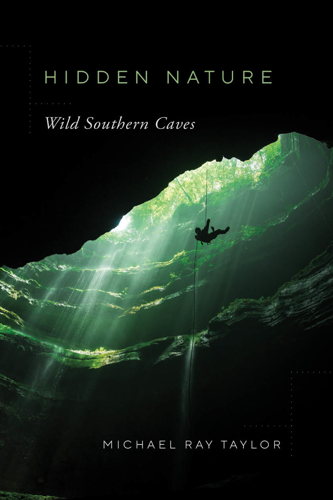

In a career that has spanned nearly 30 years, Michael Ray Taylor has emerged as a Keats of caving, a veteran explorer of underground realms who writes with grace and restraint. His new book, Hidden Nature: Wild Southern Caves, probes the daunting and delicate ecosystems of caves; the passion that drives those who seek a larger connection with the world; and the enthralling reasons the South attracts locals as well as international travelers, thrill-seekers and NASA scientists alike.

Taylor answered questions from via email.

In the prologue, you mention your “eureka” moment as a child, when you and your family took a tour through Ruby Falls, near Chattanooga. What do you make of the commercialization of caves throughout the South?

Cavers have something of a love-hate relationship with commercial caves. When I was young, such caves tended to the gaudy, with fanciful colored lights and guides who spoke of legends and fairies rather than science. But at the same time, many cavers had, like me, a love of the underground sparked from a childhood tour. The good news is that in recent decades most commercial caves have become more like those in state and national parks, delivering strong educational and conservational messages with their tours. Many of them have now added “wild caving” trips, where visitors are given a helmet, a lamp, and the chance to experience a true cave wilderness in the absence of lighted pathways. While working on Hidden Nature, I revisited several Southern tour caves, including Ruby Falls, for the first time in decades. I was pleasantly surprised by how sophisticated some of these tours have become.

As an editor at Scribner I had the privilege of acquiring and editing your first book, Cave Passages, a collection of beautifully crafted essays on the art and science of caving. A quarter-century later, what do you know about caving now that you didn’t know then?

It’s not so much what I know about caving now compared to then, but what I’ve learned about life in 25 years. I wrote the essays that became Cave Passages in my 20s and early 30s. Then as now, there was a burst of new cave discovery going on, and it was an exciting time to be a young man joining expeditions to search for caves, often in distant and exotic places. As I’ve gotten older, the caves have stayed pretty much the same — they age on a geologic time scale. But I’ve gotten older, and so have my caving friends.

Lee Pearson, my caving buddy who appears in both books, nearly died twice from heart attacks, and I’ve been through prostate cancer, yet we still cave together whenever we can. Others I knew then have died, sometimes in tragic caving accidents. As cavers like me return to these magical, unchanging places beneath the surface, we can’t help but contemplate our own mortality. The reflection that such trips ignite has made me appreciate the lasting bonds that form underground. My first book was mostly about exciting caves. I feel that this one is more about interesting cavers as much as it describes the places they dare to explore.

I learned a new term from Hidden Nature: “spelean biology.” Could you elaborate?

My wife would slap you upside the head for that question. She’s heard me “elaborate” on spelean biology through entire dinner parties. I find spelean biology so exciting, once I get going it’s hard to shut up. Scientists have always known about bats, blind fish, salamanders and other common cave life, but over the past 30 years there’s been an explosion in new understanding of a vast microbial ecosystem that seems to lie beneath the entire planet — by weight, representing the bulk of life on Earth. Caves provide a window into this mysterious world, where microbes consume rocks, secrete acid to make more caves and live perhaps millions of years with no oxygen, sunlight or other ingredients we have always thought of as necessary for life. Cave microbiologists like Hazel Barton at the University of Akron are redefining life, not just on Earth, but as it may exist on many planets and moons. In the process, they are making discoveries that could lead to useful products for humans. Some of the research I describe in the book has only just begun. Young scientists rappel into caves and make new discoveries daily.

Briefly, what do caves reveal about our escalating climate crisis, more visible on the Earth’s surface, with rising sea levels and scorching record temperatures in Siberia?

Like the rings of trees, cave formations can record changes in climate as they grow — the main difference being the formations can be tens of thousands of years old. Recent cave studies pinpoint the advance and retreat of glaciers during various ice ages, while others demonstrate changing water tables from aboveground development and agriculture or the gradual pollution of groundwater. When brought to light, this evidence can foster positive change. For example, a cave in Cookeville, Tenn., called Capshaw was contaminated with sewage runoff for decades — when I first saw it in the early 1980s, locals had nicknamed it “Crapshaw.” As I write in the book, environmental action by cavers and others has made Capshaw much cleaner today than when I first visited. This means local groundwater is also cleaner.

In one chapter you note the roles caves have played in our cultural imagination, from the sublime — “Homer, Plato, Dante, Virgil, and Blake” — to the ridiculous, such as a 1959 B-movie, The Beast from Haunted Cave. What misconceptions seem entrenched among non-cavers?

One is bats: Bats will tangle themselves in your hair (especially if you are a blond woman), suck your blood, give you rabies and all sorts of bad things. The reality is that bats are small, amazing creatures that eat mosquitos and pollinate plants. They deserve our protection, not fear. Then there’s monsters: Blind, albino genetic freaks abound in Hollywood caves, but not so much in the actual ones I’ve explored. And cave-ins. Cave walls often stand for many centuries, but in movies a loud sneeze will send them tumbling down. That’s not to say that caves are without danger. When you cross a cave canyon by a natural bridge that begins to collapse beneath your feet, you can’t help but feel like you’re trapped in a pop culture cliché. Luckily that’s only happened to me a couple of times. Mostly caves are much safer than the memes would have you believe.

As with Cave Passages, Hidden Nature showcases science/adventure narrative at its finest, reminiscent of John McPhee’s Assembling California or Jon Krakauer’s Into Thin Air. In what specific ways do the arts of caving and writing complement each other?

You mention two of my favorite nonfiction writers. I was a caver before I started writing, but once I did, McPhee and Krakauer particularly inspired me to capture the essence of a unique place and the characters who inhabit it. Even better is when a writer can set people and place amid stark physical danger. This is the essence of American realism, as first developed by writers like Stephen Crane and Jack London, then carried forward for over a century by a host of good writers from Hemingway to Susan Orlean. To simply describe what is there — when “there” is an almost indescribable place — is hard work, but to me it is the goal of all good nonfiction.

Has the rise of social media helped or harmed the caving community?

It’s helped, definitely. Cavers who used to share new finds only in guarded terms around a campfire now post detailed trip reports on Facebook. As with all affinity groups, cavers have embraced social media as a means of sharing what’s happening in their world with like-minded individuals. I knew that Hidden Nature was going to jump back and forth between scenes of personal memoir and recent discovery, and I knew I would need some sort of transitional device to keep readers from being jarred too much between past and present chapters. Social media posts, which appear in the book as “Social Interludes,” gave me that device. With the permission of the authors, I shared glimpses of many Southern cavers who don’t otherwise appear in the book. As I answer this question, I have responded in the last hour to new cave discoveries posted online. While social media may be just a literary device for me, for cavers it empowers collaboration and new discovery.

In the summer of 1966, when you met Miss Ruby Falls, I was a toddler whose parents were moving into 29 Sylvan Drive in Ormond Beach, Fla., your hometown. The subdivision was named Tomoka View Estates, near the Tomoka River. How did growing up in that landscape influence your later career as a caver?

As a teenager I had a small boat with which I explored the Tomoka River and its tributaries. I walked through ruined plantations and historic sites, then spent hours in libraries learning what had transpired there. At nearby springs, I peered into underwater caves that spouted rivers of pure water from ragged openings in the limestone bedrock. These excursions primed me to explore surface caves in the Florida Panhandle when I went to college. But the fact that I am now being interviewed by a guy who grew up where I did and who also edited my first book — which focused on synchronicity amid otherwise disparate cave trips — suggests that I was opening myself even then to coincidences that somehow bring meaning to disconnected events, that led me to the deep underground, where I learned that everything is connected.

In one sentence, could you summarize what lures you and your colleagues underground, exposing yourself to mud, danger, disruptions to delicate ecosystems?

Mountain climbers risk death “because it’s there,” but cavers descend into the depths to discover what is there, to see places previously unseen, to bring light where no light has been.

For more local book coverage, please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.