John T. Edge

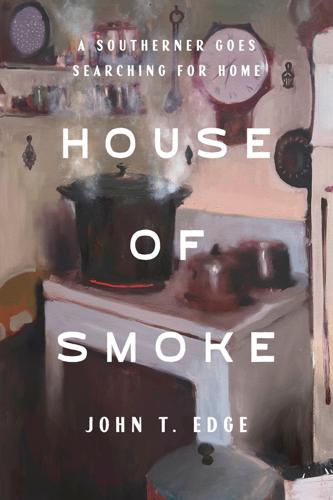

For years, John T. Edge has been a leading voice in the South, primarily through his role as founding director of the Southern Foodways Alliance. At SFA events and in his 2017 The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South, Edge focused his attention on the abundance and diversity found in Southern cuisine. In his new memoir House of Smoke: A Southerner Goes Searching for Home, he turns the spotlight on himself, probing the Lost Cause mythologies he grew up believing and later turned away from. He also reckons with the parts of his story he has kept hidden, including his late mother’s alcoholism and the outside violence that shook his childhood home.

“Telling stories about other places and other people,” he writes, “I draped my home in a cloak, hiding our life there from view, trying to convince magazine readers and symposium audiences that the important narratives of my life began at Old Clinton Bar-B-Q in one of those ladder-back chairs, with a vinegar-doused sandwich in hand.”

He goes on to explain that “those stories were true. But they weren’t the whole truth.” After a 2020 panel discussion in which chef Tunde Wey called for him to step down from the SFA, Edge was forced to face the truth: There was much more to his story for him to explore. The memoir comes from that exploration, one man’s attempt to reexamine his past and perhaps find a new way forward. Edge answered questions via email.

House of Smoke insists on the importance of change, of being willing to change. What change do you still hope to see, both in yourself and in the South?

Change requires telling old stories in new ways. House of Smoke is about rewriting the stories I inherited from the South and from my family. As a boy, I believed that Confederate Brigadier General Alfred Iverson, born in my house in Clinton, Ga., was a hero of the Civil War. Writing this book, I learned to tell that story, and others, in new ways.

I title one of the later chapters “Reconstruction.” I hope to attract readers who recognize that, with each rewrite I make, each change I embrace, I reconstruct myself. My hope for the South is much the same as my personal aim: Learn to embrace change. Be suspect of resistance couched as tradition. A generation from now, I would love to hear country artists singing about what we’ve found instead of what we’ve lost.

You write of how much of your life has been spent performing for an audience, even if that audience was only your mother. Who is your ideal reader, the audience member you most hope to reach?

My mother, Mary Beverly Evans Edge, was a woman of great social intelligence with an outsized personality. My want to step into the spotlight was born of her dreams. She also faced big challenges, betrayed by the chemicals that coursed through her body. With House of Smoke, I honor her. In my search to reconcile with her and with the place where she came undone, I want to reach readers who carry forward complicated family relationships and mixed feelings about the places that made them. I hope my story inspires readers to take on comparable searches.

What changed for you once you wrote about your mother’s catfish stew?

That Oxford American column was a genesis of this book. On the other side of that essay, I began to recognize two things: My family story has power. And my family story can inspire readers to grapple with their own stories.

Concerning the events in 2020, you write, “Hubris undid me,” and you recount the words of chef Tunde Wey, who told you that your time was up. Looking back, is there anything you would change that could have made that situation different?

In the summer of 2020, when the New York Times published a critique of me and the Southern Foodways Alliance (which I then directed), I learned new lessons about when to listen and when to speak. I thought I’d already learned those lessons. But like many of us who try to make change in ourselves and our places, I was backsliding. Change is hard. Backsliding is inevitable. I was working to fix the South when I hadn’t done the work to fix myself. I hadn’t yet absorbed the story I told in “My Mother’s Catfish Stew,” the story I tell with more depth and reflection in House of Smoke.

What are the projects you have on the horizon that most excite you?

Season 8 of TrueSouth, the television show I make with Wright Thompson (executive producer) and Tim Horgan (director), debuted Sept. 2 on the SEC Network. If you haven’t seen an episode yet, this is our model: Take two restaurants in one place, tell the stories of the people who run those restaurants and the people who call those restaurants home.

In the process, we sidestep the myths and half-truths that obscure the South to tell complicated and layered stories. That format has allowed us to tell about recovery from addiction in Dublin, Ga.; father-son dynamics in Lexington, Tenn.; and the impact of economic change in Lake Village, Ark. Back in Season 3, we broke open that formula to tell the story of my mother’s catfish stew and stage the funeral she never had. In many ways, that episode broke me open.

Mississippi gave me the skills and belief to become a writer. Now I’m working to give back to the state that made my work possible. Fifteen miles outside of Oxford, where my wife Blair Hobbs and I live, I’m working with colleagues at the University of Mississippi to build Greenfield Farm Writers Residency.

Set on what was once William Faulkner’s mule farm, we will open, if all goes well, in the first quarter of 2027. No one will pay fees. Writers of all genres, from screenwriting to poetry, will be welcome. Guests in the overnight studios will receive $1,000-per-week stipends. Greenfield Farm Writers Residency will be a new front porch for Mississippi.

For more local book coverage, please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.

The annual event takes place Oct. 18-19 at Bicentennial Capitol Mall State Park, the Tennessee State Museum and the Tennessee State Library & Archives