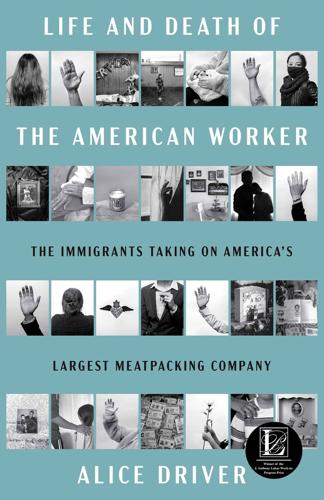

Alice Driver

Sorry, but there is no way to tell you about Alice Driver’s Life and Death of the American Worker without disgusting you.

Here’s what Victor, a machine operator at Tyson Foods’ Chick-N-Quick plant in Rogers, Ark., has to say about the ingredients in chicken nuggets, according to the book: “Many times, the chicken is rotten,” Victor says. “It smells. It arrives like a rock. When we open it, it is already a different color, not pink. It is green or purple.”

Driver, a native of Arkansas, is a journalist and translator who writes about migration, human rights and gender equality. Her book tells more disturbing stories about the immigrants Tyson puts to work making their products, how Arkansas politicians including the Clintons have carried Tyson’s water, and the health hazards in their meatpacking plants.

We spoke with Alice Driver ahead of her appearance at the 2024 Southern Festival of Books. The discussion has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Why were you attracted to Tyson and the meatpacking industry as a story?

I’m from the Ozark Mountains, and there is a Tyson plant about 45 minutes from where I grew up. I grew up in a town of 200, and a lot of people in that town worked at Tyson, so I grew up with chicken houses around and following Tyson trucks full of chickens. … Some of the first immigrants I met were Tyson workers.

A lot of the stories in the book are depressing. Was it difficult to report and write the book?

It was very difficult. It’s heartbreaking. I followed a group of workers for four years. Some of them died. Many of them got COVID. … In one case, nobody claimed the body of a worker who died because everybody was sick with COVID. It’s the most challenging project I’ve ever done.

It must be rewarding to give these workers a voice since it’s become commonplace to demonize immigrants.

These are the people who are upholding the food system in the United States. Many of them are undocumented. Many of them are immigrants or refugees, and they are doing absolutely backbreaking work. The reality is that all of these major companies — my focus is Tyson — absolutely rely on these workers, and we rely on them for the food that arrives to our table. I wanted to look at the strength and the moral beauty of these workers because that’s the conversation we should be having.

Does it matter to meatpacking workers who wins the U.S. presidential election?

The meatpacking lobby, they give money indiscriminately. They supported Clinton, they supported Bush, so they’re going to support whoever wins. But does it matter if Trump wins? Absolutely, because as I recount in my book, at the height of the pandemic when people were getting COVID and dying and it was spreading throughout meatpacking companies like wildfire, there was an opportunity to say we should shut down plants. We should do contact tracing. We should take care of these workers. We should ensure there’s social distancing if we are going to keep [the plants] open. What happened instead was that the major meatpacking companies, Tyson included, met with the Department of Agriculture. They had discussions with Vice President Pence, and right after they did that, Trump declared that all [meatpacking] facilities had to stay open because it was necessary to provide food for the United States. In reality, meatpacking companies were exporting a lot of their meat anyway, so it wasn’t really an issue of domestic production. It was an issue of profit.

You also show that racism is rampant in this system in the relationship of Tyson to prison labor. Would you explain?

I found out that Tyson buys corn from an Arkansas prison, which is at the site of a [former] plantation. Black people only make up a small percent of the Arkansas population. They’re a large percent of the prison population, and they are growing the corn for zero dollars that Tyson buys from the prison system. So all these ways that they’re saving money are really rooted in racism.

Is the solution unionization?

We need more oversight. We need unions. We need support for workers who don’t speak English and often have no translator at work.

You don’t spend much time in the book on the Tyson family. Why?

I include some descriptions of the members of the family, like Don Tyson. [The Tyson family has] houses all over. They go to Cabo. They have a huge art collection. I want to contrast that with the state of the workers.

To read an uncut version of this interview — and more local book coverage — please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.

Oct. 26-27 in downtown Nashville, the festival will celebrate literary excellence close to home