Ada Limón

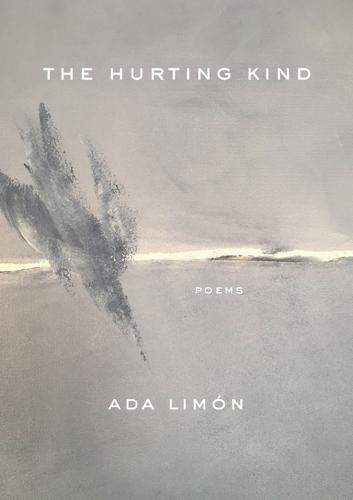

In her career as a poet, Ada Limón has been much celebrated. Her 2018 collection, The Carrying, won the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry, and her work has been nominated for the National Book Award and Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award as well. She was named the 24th U.S. Poet Laureate in 2022. Her latest collection, The Hurting Kind, has been lauded for the way it blends the mysterious with the ordinary, the everyday with the exceptional. Her work is known for being accessible while still elevating readers, urging them into wonder and curiosity.

Originally from Sonoma, Calif., Limón now makes her home in Lexington, Ky. She recently spoke with the Scene by phone. The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

The idea of making music or singing crops up frequently in your work. Do you see yourself as making music with your poems?

Unlike the incredible musicians we have both in Tennessee and Kentucky as well as all over the world, poets don’t get to work with all the music. We don’t get to have the guitarist and the bass line and the drums. We have to make all of that on the page. And so the whole poem has to be the song, and it has to have all the instruments and all the harmonies and the melodies. And I feel like when I’m writing, I’m aware of that. There is a type of singing that’s happening, and the singing is spoken, of course. But there is a level in which the musicality is high, especially in the work I’m most drawn to.

The other part of that is there’s a way that singing calms us, like the way you sing to a child or the way you come into communion or in community with other people. Singing together is such a powerful bond, and I think that way of making music on the page and offering something back to the world is a kind of rebellion, but also a celebration at the same time — a rebellion against everything that is suffering. But then also, a celebration of everything that’s alive and whole.

In both The Hurting Kind and The Carrying, the opening poems focus on a woman seeing and knowing an animal and then turning that knowing gaze back on herself — wanting to be similarly known and seen. What makes animals such an effective tool for this reflective process?

It’s true. It didn’t take me very long to realize that The Hurting Kind is a book of animals. I knew it. This is a book of animals, but it’s also about ancestors. It’s the animal ancestors, right? So much so that I remember thinking, I want to write a poem about my brother and snakes, because I felt like there were no snakes. I needed to have some snakes. So I was actually making some poems based on the recognition I was in the Kingdom Animalia. I think my curiosity and my interest in them is that we just don’t know anything, and the best scientists and all of the people who work really closely with animals, they know a lot. But there is still such a mystery.

In the past couple of years, when I’ve started seeds under a grow lamp, I loved watching them slowly become the thing that would go into the ground, somewhat like the way a poem can live inside you for a while before it’s ready to take shape. How has the act of gardening or being in the natural world spoken into your work over the years?

Yeah. It’s funny. I think that there are years when I’ve traveled, and so I’ve planted but then never tended. And then I just see what happens. And then there have also been moments when it has become an obsession, and I want everything to be perfect, to grow the most perfect tomato you’ve ever seen. But what I love about it is that you just can’t control it.

It’s not unlike poetry. It’s not unlike writing. You can think that you know the outcome, but in reality, nature is going to do its thing, and a poem is going to do its thing. You might think, Oh, I’m going to start out by writing this poem with this memory. And then in reality another poem happens on the page right in front of you, and you weren’t even prepared for what it was going to tell you or teach you. Often people will call what we write drafts, but to me a draft is a little more finished. So when I do workshops, especially if I say we’re going to write something in five minutes, and then move everything around, I say they’re not drafts — they’re seeds.

To read an uncut version of this interview — and more local book coverage — please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.