“Help Save the Youth of America,” read a flyer of the 1950s from the segregationist White Citizens’ Council. “DON’T BUY NEGRO RECORDS.” As Michael Bertrand continuously demonstrates in his fascinating new book, Southern History Remixed, popular music shaped how Black and white Southerners understood and engaged with one another. Music could both unite and divide. It is a history that hits more than one note — it twangs and jangles and rumbles.

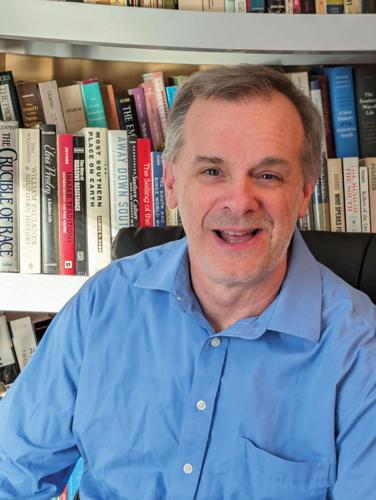

Michael Bertrand is a professor of history at Tennessee State University. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Memphis. A scholar with interests in popular music, popular culture, memory and social change, he is the author of Race, Rock, and Elvis. He answered questions via email.

This book was born after you read an editorial from 1956 by James Wechsler, the crusading liberal editor of the New York Post. What was the message, and how did it shape Southern History Remixed?

It started with the editorial’s title, “The Bystanders.” Wechsler was commenting on the onstage attack by White Citizens’ Council members on Nat “King” Cole in Birmingham, Ala. As he noted, racist paranoia over the popularity of rock ’n’ roll among white teenagers precipitated the assault. Over 3,500 “decent human beings … watched in passive horror” as a handful of ruffians battered the performer. They later cheered and apologized to the singer, but the audience’s failure to rescue Cole resonates. Reading the editorial, it struck me that Wechsler was hinting that the Cole attack appeared made to order for future historians grappling with a changing American South’s encounter with the modern Civil Rights Movement. I end the book with the phrase, “It’s complicated.”

Southern society sometimes appears paradoxical. On one hand, it has enforced racial separation. On the other, Black and white people interact closely, with a cross-fertilization of cultures. Can music help explain this paradox?

The key is U.B. Phillips’ article, “The Central Theme of Southern History,” in which he states that “the South shall be and remain a white man’s country.” What drove Phillips was his belief that a biracial Southern society would not produce a biracial Southern culture. But he was wrong. Anyone who charts the interrelationship between musical and cultural trends in the South recognizes the tension inherent in conflating regional identity with whiteness. The study of music likewise calls into question the cultural efficacy of segregationist policies and conventions among those Blacks and whites who were politically, economically and socially marginalized. Despite the erection of the color line and laws limiting physical interaction, their similarities were more prevalent than their differences. Their potential for unity, in opposition to an oligarchical system oppressing them, was very real. And threatening.

Michael Bertrand

In the era after World War II, Black-oriented radio stations popped up around the South. How did they shape Southern history in this period?

It is complicated, because most of the Black-oriented radio stations were white-owned. Nevertheless, in the late 1940s the emergence of African American radio programming played a large role in countering the Jim Crow imagery so vital to a segregated society (and earlier radio programming). Every major Southern city had at least one radio station that aimed its programming and on-air personalities toward a Black market; the impetus, of course, was advertising dollars. Following World War II, the South enjoyed a prosperity unprecedented in the 20th century. African Americans partook of this affluence. Trying to reach those listeners and their dollars, programs emphasized racial dignity, respect and affirmation. Not insignificantly, those tuning in would include future Black student activists and white rock ’n’ rollers.

When we think about white Southerners during the civil rights movement, we tend to focus on those who harassed, beat and oppressed Black activists. If we approach the period through the lens of rock ’n’ roll, does it complicate that picture?

Yes. The white student response was never monolithic. The voices of white teens often expressed ambivalence toward segregation and acceptance of desegregation, with students frequently mentioning their attachment to rhythm and blues or rock ’n’ roll. Balancing the perspective as presented in the question, for example, are descriptions of frustrated young white segregationists outside of a school angrily yelling toward the building demanding that their peers join their demonstration. Significantly, most did not. As troublemakers returned to class and terrorized Black students, the majority of whites did little to counter. They did not join in the terrorism, but neither did they stop it. Many of the students may regularly have attended an off-campus morning Black-DJ-hosted radio show on the way to homeroom. Paradoxically, white rock ’n’ rollers generally did not march for civil rights. But it is what else they did not do, and why, that draws our attention.

To read an uncut version of this interview — and more local book coverage — please visit Chapter16.org, an online publication of Humanities Tennessee.