Eve's Bayou

I’m hoping you had a nice Valentine’s Day, or whatever your personal commemoration of choice is for the day before all the candy goes 50 percent off. This week’s films are not particularly romantic, nor are they useful as aesthetic litmus tests for potential amours (unless you’re particularly hardcore when it comes to your cinema — in which case, respect). But these are films that dig deep into human experience and do not play around when it comes to big, complicated emotions. I hope you’re getting by, and that you’re cared for. I hope the state makes sure everyone gets a COVID vaccination instead of a gun, as the latter is apparently their priority right now. And I hope your candy of preference is in the post-holiday discount section, because it’s the little treats that keep us on the right side of the gator fence at the emotional zoo we are all currently living in. As always, look at past issues of the Scene for many, many more recommendations of what to stream: March 26, April 2, April 9, April 16, April 23, April 30, May 7, May 14, May 21, May 28, June 4, June 11, June 18, June 25, July 2, July 9, July 16, July 23, July 30, Aug. 6, Aug. 13, Aug. 20, Aug. 27, Sept. 3, Sept. 10, Sept. 17, Sept. 24, Oct. 1, Oct. 15, Oct. 29, Nov. 5, Nov. 11, Nov. 26, Dec. 3, Dec. 17, Jan. 6, Jan. 21, Jan. 28, Feb. 4, Feb. 11.

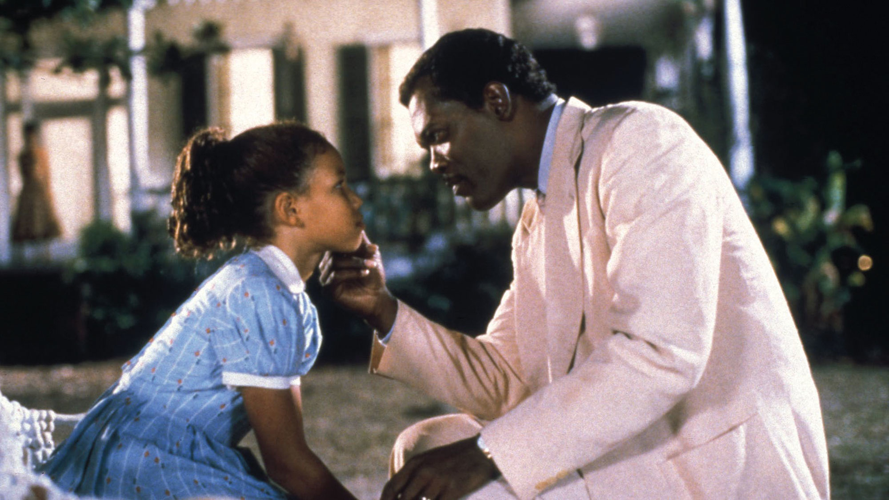

Eve’s Bayou on Hulu and Amazon Prime

It’s messed-up how limiting the language we use to commend art can be. When we talk about great works of creation devoted to the travails of the Southern family, it is customary to work in the medium of comparisons to artists like Flannery O’Connor, or Tennessee Williams, or William Faulkner. They’re all tremendous writers, yet comparisons to them implicitly reinforce the whiteness that achievements in that field are held up against.

So what happens when we talk about Eve’s Bayou? The 1997 directorial debut from actor Kasi Lemmons (Candyman, The Silence of The Lambs) is a masterpiece of Southern Gothic, well-versed in the violent history of American genealogy and the variations of swamp witchery to be had, a Rashomon of how diaphanous and imprecise notions can become something tangible and dangerous. But the only explicit references to race and class come at the very beginning, when we are informed that the Batiste family is descended from a French military officer and the Black woman whose knowledge of herbs and medicine saved his life. So the drama that unfolds is built on the foundation of several generations of red hair and second sight, and though there is a distinctive Southern tragedy at work, the story of the Batiste family would have been just as enthralling to Aeschylus — there is some strife we as human beings can never escape.

The women in this film play a remarkable assortment of characters — Debbi Morgan’s Mozelle, occasional seer and cursed to lose every man who takes her hand in marriage, is the story’s heart and soul. Neither victim nor victimizer, she has the gift of perspective (which is certainly apt for a fortune-teller) and a just-this-shy-of-ghoulish sense of humor. Eve’s Bayou has a kind of radiant endurance, and I would absolutely watch a series devoted to the rivalry between Mozelle and Elzora (Diahann Carroll!), the other fortune-teller/mambo who hangs out at the marketplace by the river.

If you’ve never seen this film, you should absolutely remedy that. It is a landmark in ’90s independent cinema, and one with great power undiminished by the intervening decades.

Beginning

Beginning on Mubi

Writer-director Dea Kulumbegashvili made her feature debut with the focused and devastating Beginning, and I’m still in awe of what she accomplishes in it. There are touchstones to be found for anyone who digs rigorous art cinema of the 20th century (Bresson, Tarkovsky, von Trier, even Breillat, Tolkin and Reygadas) and likes to play thematic trainspotting. But Kulumbegashvili is doing her own thing, and there aren’t simple comparative points to fit what she’s doing into a safe context. This is a film about religious persecution, human nature and the way that power structures sustain themselves by clinging to outmoded hierarchies and ideologies.

Iana (Ia Sukhitashvili) and her husband David (Rati Oneli, who co-wrote the film with Kulumbegashvili) are part of the small Jehovah’s Witness community in an isolated part of the nation of Georgia. Their community is subject to indifference (at best), abuse and violence at the hands of the majority Georgian Orthodox population, with the ongoing small acts of aggression (as well as utterly horrifying larger acts of aggression) piling up, leaving Iana and David wondering if it’s even worth it.

Kulumbegashvili has a gift for dramatic tension and utilizing off-screen space in a way that makes it very difficult to let your guard down as a viewer. The very first shot of the film makes it apparent that we’re in new territory as far as narrative guardrails are concerned, and though there are moments of an almost preternatural grace to be found, there’s not anyone in cinema to use for comparative sake. Though a formalist, Kulumbegashvili does not follow that aesthetic path through to becoming a scold (Michael Haneke, this means you), nor does she reverse-engineer the film to yield maximum cringe based on the audience’s response to the material as presented. And when Beginning lays into the throttle (relatively) in its last reel, it finds a common ground between the visceral and the transcendent in a way that had me dumbstruck and wishing I could see this on a proper giant IMAX screen. (Think Being There, Gerry and Raiders of the Lost Ark, but all at the same time.) The 2020 New York Film Festival was an overwhelming banquet of exceptional work, but this was my favorite, and there hasn’t been a day since that Beginning hasn’t haunted my subconscious in some fashion.