Dawn Porter’s exceptional documentary John Lewis: Good Trouble offers a comprehensive and fascinating portrait of a life devoted to multiple battles for social justice, voting rights and economic equality. Porter’s production differs slightly from 2017’s equally noteworthy PBS documentary Get in the Way through its blend of amazing archival footage (some of which even Lewis acknowledges he’s seeing for the first time); reflections and assessments on his impact from various political figures, educators and activists; and family remembrances that delve into other areas of Lewis’ life that have been given less notice.

The film — which will be available to stream via the Belcourt’s site on Friday — doesn’t take a straight path to the present, instead alternating between spotlighting key political and personal moments in Lewis’ 60-year career. His thirst for knowledge and love for reading at a young age didn’t exactly make Lewis an ideal worker on the family property in Alabama, but it fueled a desire to do something other than pick cotton and raise chickens. He came to Nashville as a student (he studied at both American Baptist and Fisk), and his time here in the early ’60s forever shaped his destiny. Lewis was mentored by such greats as the Rev. James Lawson and schooled in the power of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience. This became the foundation for his life’s philosophy and attitude — a mix of unshakable optimism and the knowledge that change never comes quickly, and seldom without cost.

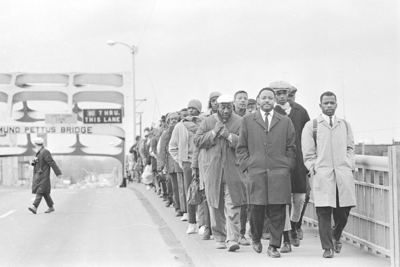

The documentary features footage of the brutality waged against college students demonstrating in downtown Nashville, the Freedom Riders in South Carolina and the marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Alabama. That material is no less vivid and shocking today than it was decades ago, and Lewis was right at the center of numerous epic events. He spoke as part of 1963’s March on Washington and served as head of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, often standing side by side with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Andrew Young, the Rev. Ralph Abernathy and other civil rights stalwarts. He recalls being extremely close to Robert F. Kennedy prior to his assassination — an event that triggered his decision to move from being an activist operating outside of the system to running for office and attaining a position within it.

The film doesn’t overlook setbacks Lewis has suffered, from the physical brutality he endured at the hands of cops and racist white onlookers at demonstrations to the pain of losing his position at SNCC to Kwame Ture (formerly known as Stokely Carmichael) due to his refusal to embrace or endorse the emerging Black Power movement. Lewis’ view was that the civil rights struggle, and indeed all social justice movements, must be both nonviolent and multiracial. That stance doesn’t always sit well with more radical types — people who feel that ideology dilutes the impact and importance of Black voices, particularly in organizations created by African Americans. Also included in Good Trouble is Lewis’ 1986 campaign for Georgia’s 5th Congressional District, which pitted him against longtime friend Julian Bond in what turned into a bitter, ugly battle, with both men throwing accusations against each other. Also shown is Lewis’ disgust over the Supreme Court’s gutting of the Voting Rights Act in 2013, and the failure of Congress to support new efforts to restore its original power.

Good Trouble consistently shows how much respect and admiration Lewis enjoys. Over the course of his career he’s been idolized not only by congressional veterans like House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the late Elijah Cummings, but also newcomers like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Ilhan Omar, who cite him as an inspiration for their interest in politics. He has also forged close bonds with newer figures like Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacy Abrams and Texas activist Lizzie Fletcher. The film’s only shortcoming is that it features no discussion of Lewis’ recent battle with pancreatic cancer, nor about his feelings on such current groups as Black Lives Matter. His perspective regarding ongoing demonstrations against police brutality and systemic racism would have been welcome.

But so much about Good Trouble is vital and valuable. Now 80, Rep. John Lewis has helped make some major positive changes in American society. While he clearly feels that much more remains to be done, he’s fought to bring America closer to its ideals.