Music Row’s long history of commercial country hits is synonymous with many icons recognizable by just their first names — Dolly, Patsy, Johnny, Hank. But thrice-named singer, songwriter, producer, label owner and painter Robert Ellis Orrall is emblematic of the irreverent, eccentric spirit that has helped forge Nashville’s contemporary independent music scene.

After coming of age in his native Massachusetts’ rock scene, Orrall signed with RCA records in 1980. He and Carlene Carter both scored their first Billboard Top 40 appearance with their 1983 duet “I Couldn’t Say No.” In the video for the song, Orrall has a shaggy haircut and wears a skinny tie, singing at a piano like a post-punk Billy Joel. Carter — the daughter of June Carter Cash and her first husband, singer Carl Smith — is country music royalty, but when her intense vocals splash into a wave of 1980s rock reverb, she’s more Pat Benatar than Patsy Cline.

Orrall’s early successes blossomed into a career of searching out the connecting points between country, rock, punk and avant-garde music. At their best, all those genres are partly characterized by their lack of artifice. The colorful domestic narratives in Orrall’s painted canvases also lack artifice. Some of them are hilarious, and the best include texts of personal stories and observations that can make the disarmingly simple images surprisingly potent.

“I started painting in 1998,” Orrall tells the Scene by phone. “I started seeing a therapist, and it was the first time I’d done therapy, and I fell in love with it. That’s what got me into all my childhood stuff. My sixth-grade teacher said I wasn’t a good artist and never would be. I kept painting things about childhood because I was investigating childhood. I was writing my album Gravity about my childhood, and I knew I could paint those childhood stories because I was still the same artist as I was then. My sixth-grade art teacher taught me to be afraid of art. I’ve painted that scene 13 or 14 times because people really like that one.”

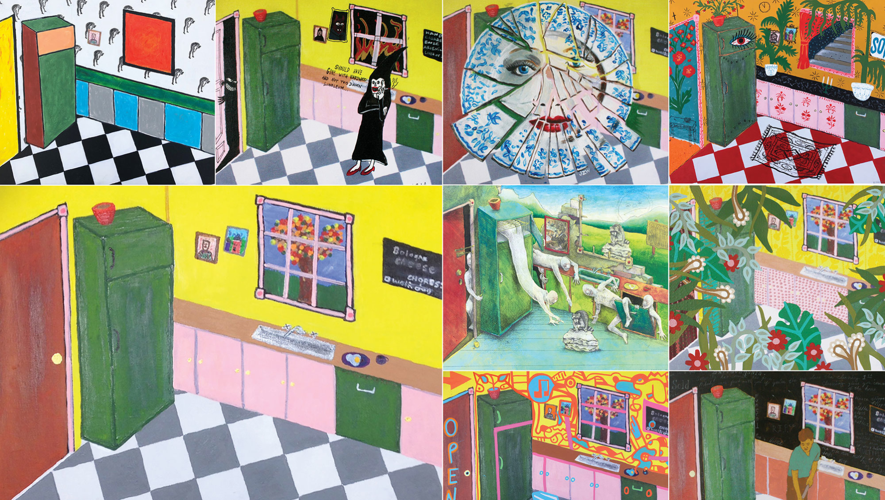

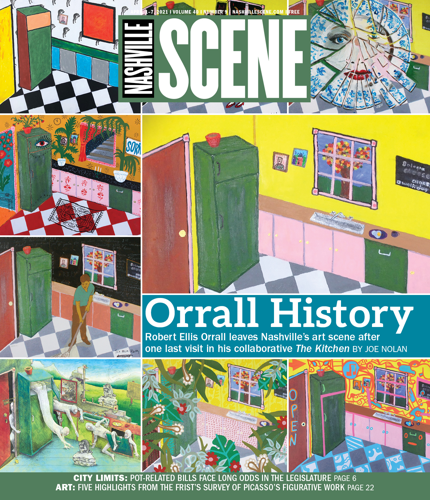

Orrall painted an image of an ordinary-looking kitchen space while working in his Art Shack studio outside of Fort Houston back in 2015. Before he finished the piece, he photographed the plain painting of an empty kitchen and asked himself what other artists might put in his kitchen. Orrall had the photograph printed on canvases of various sizes and shapes, distributing them to his art-scene peers to finish in their own styles. Orrall and his collaborators — more than 30 of them — open The Kitchen at Julia Martin Gallery on Saturday, and the show’s roster reads like a wild cross-section of Nashville’s visual-art community: Richard Feaster, Brett Douglas Hunter, Harry Underwood, Bryce McCloud, Juliana Horner, Bongang, Jen Uman, gallery owner Julia Martin and more. The show is a testament to the impact that Orrall, his family and their indie record label Infinity Cat have had on the city’s visual art scene. It’s also the artist’s farewell to a place where he and his family have thrived for three decades.

After his run of rock records for RCA, Orrall moved to Nashville with an eye on songwriting and producing. He crafted hits for other artists, including Shenandoah’s infectious Billboard Hot Country Songs No. 1 “Next to You, Next to Me” with Chris Wright. The pair released their own self-titled album as Orrall & Wright for Giant Records in 1994. The act was nominated for Duo of the Year by the Country Music Association, but Orrall focused on developing new musical talent and working on his own chops as a painter.

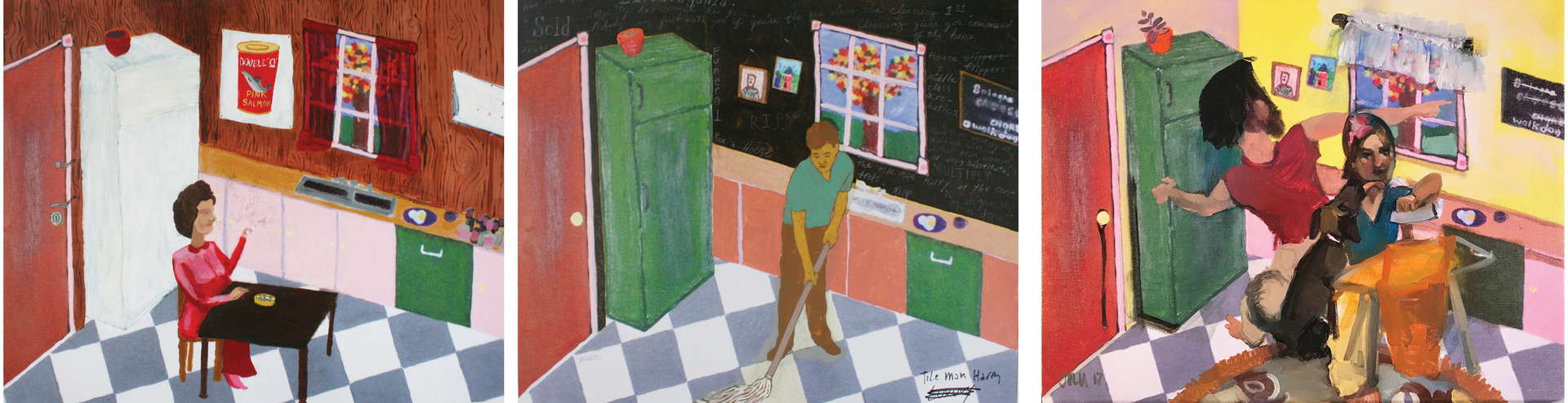

Flash-forward a couple decades. Orrall finishes his original painting of the kitchen by pasting a tiny reproduction of a photograph to the inside of a door and adding a portrait of himself in a flattop haircut and blue jeans, standing on a checkerboard tile floor. The image on the door is of 1970s model and actress Twiggy, her face framed by a fur collar. Orrall adds her name to the photo and paints the iconic red-and-white Life magazine logo in the upper-left corner of the image. Orrall also adds a larger text section over the cupboards and floors on the opposite side of his kitchen scene: “If I die without kissing you how will I ever know I lived?”

Painting might seem like an odd pursuit in the middle of a busy music career, but at the turning of the millennium, Orrall’s creative path went decidedly indie.

“I started out just wanting to be a songwriter,” says Orrall. “I was 38 when I moved to Nashville, and that was old for a country music artist or any other music artist. Later on I started painting, and then my kids started making music. I became more interested in the way they were making their music, which was bizarre and I didn’t understand it. One weekend they were talking and said, ‘Dad let’s make a record label.’ ”

Infinity Cat, the Orrall family business, thrived on both the DIY spirit of indie music making and the homespun aesthetics frequently produced by creative practices outside the mainstream. Orrall and his sons, Jake and Jamin, formed Infinity Cat Recordings in 2002, and the label eventually established itself with releases by the Orrall brothers’ band, JEFF the Brotherhood, as well as punk and indie-rock groups like Be Your Own Pet, Diarrhea Planet, Daddy Issues and others. The label pulled in a cult following, and in 2011, Billboard named Infinity Cat one of its 50 best indie labels in America. Orrall was firing on all cylinders: developing new artists for the label; co-writing songs for Lindsay Lohan (2003’s Freaky Friday opens with her performance of “Ultimate”); and having his paintings represented by the dearly departed downtown gallery, Estel.

“The first person to show my art was Janice Zeitlin at Zeitgeist,” says Orrall. “Then [The Mavericks’ keyboardist] Jerry Dale McFadden put me in a bunch of shows at his gallery, TAG. I think that’s how I connected with Cynthia Bullinger at Estel. When I was in junior high school I never finished a science fair. At Estel I did a show of 12 science fair projects, and they started to have school kids come in to tour it. For me, sometimes art is a way to crack myself up.”

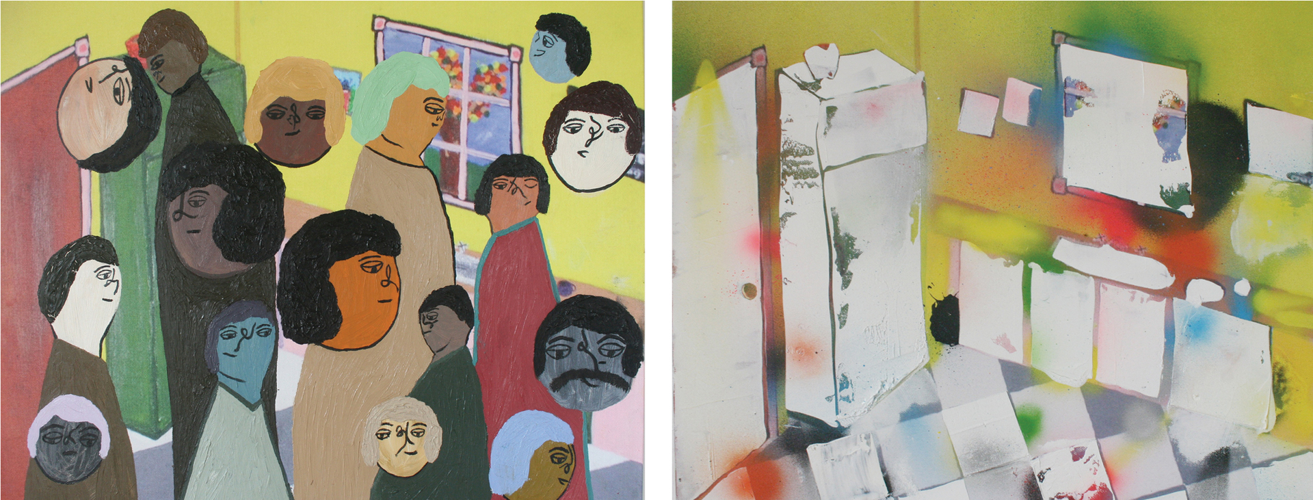

From left: Jessica McFarland, Harry Underwood, Julia Martin

The Kitchen features collaborations with some of the artists who were on the scene during the early years of the First Saturday Art Crawl, when Estel was helping establish downtown Nashville as a gallery destination. In his collab, Richard Feaster uses stencils and spray paint to flatten Orrall’s kitchen into a colorful geometric abstract painting. Lain York adds cut vinyl elements to his version, and his subjects make the work feel like a Colorforms playset. York adds a kid in sunglasses skateboarding on the tile kitchen’s floor, kicking up an ollie with a nose grab. There’s a cat sitting on the skater’s head while another watches the antics, perched on a small kitchen step ladder.

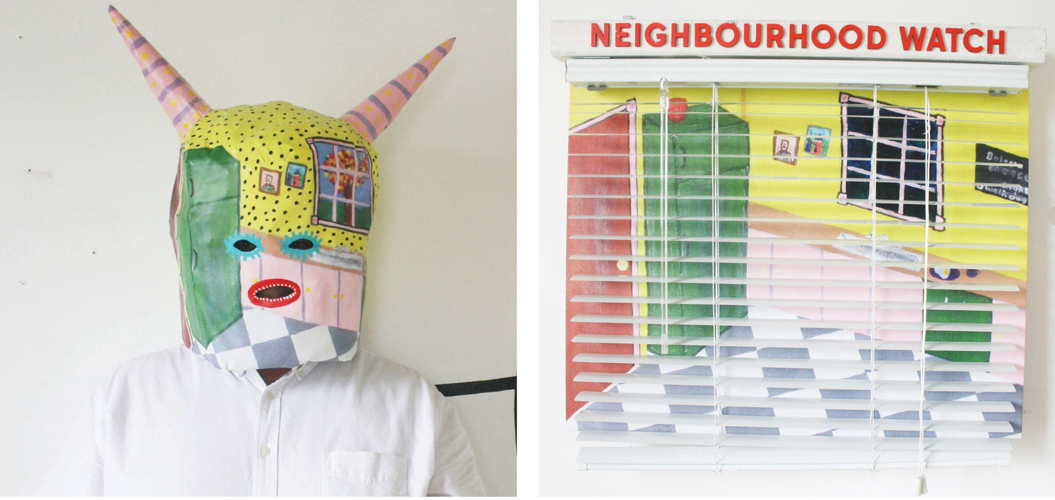

The Kitchen also includes collaborators who made their mark in Nashville’s art scene during the time that Infinity Cat and their neighbors established a new First Saturday tradition with the Arts & Music at Wedgewood-Houston events. Anna Zeitlin’s patchwork pillow offers a fabric take on Orrall’s kitchen, reinterpreting the simple painted elements as a composition of rectangular swatches featuring various designs. Another 3-D take on Orrall’s kitchen is Brett Douglas Hunter’s wearable mask sculpture, complete with weird horns sticking out of the top, plus holes for two eyes and a mouth. The eyes are outlined in turquoise squiggles and the mouth is circled in red and surrounded by a disturbing display of tiny white teeth. The rest of the mask is simply plastered over with Orrall’s kitchen painting. It looks like the two artists smashed their aesthetics together with no effort to make them blend. Luckily, it’s a perfect fit — Orrall and Hunter are both thoroughly irreverent creators. The result is the most compelling collaboration in the show. Another vibrant contribution is from muralist Bongang, whose interpretation swirls with the kinds of abstract shapes and bright, cheerful colors frequently seen in his street art. Also included is a collaboration with beloved Nashvillian Jessi Zazu, who offered her contribution before her death from cancer in 2017.

Orrall and his wife found themselves stuck in their Florida home when the pandemic came to the States a year ago. Infection rates in the Sunshine State were spiking by spring, and the pair escaped to Orrall’s home state of Massachusetts. The quiet of quarantine life and time away from Infinity Cat’s 467 Humphreys St. headquarters put the Orralls in a pensive mood. And when Orrall and his wife found a house for sale in Manchester-by-the-Sea, they bought it.

“Before the pandemic, there were a lot of things I wanted to do but didn’t feel I had time to do,” says Orrall. “COVID made those things the things I did. I finally finished an album I made with my old band from Boston back in the 1980s. But I’m 65. I wanted to slow this all down. We found this house in Massachusetts, in Manchester-by-the-Sea, where we’d lived 40 years ago when we first got married. This little house came up. We just fell in love with it. We just felt like we were home.”

Brett Douglas Hunter, Bryce McCloud

Infinity Cat is set to issue its final release — its 125th, a 7-inch from JEFF the Brotherhood — later this year. Soon the Orrall clan will all leave town, seeking new paths in new cities around the country. After a year of limited gallery-going and live music, the loss of Infinity Cat is probably not the only change we’ll see as the Arts & Music at Wedgewood-Houston events crawl back to life this spring. Change is the norm in Nashville’s ever-evolving visual arts scene — artists and art spaces inevitably come and go, and some are missed more than others.

One thing that separates artists from non-artists is that artists know when a work is completed — they put down the brush, they unplug the guitar. Artist Harry Underwood sums up the greater meaning of the exhibition best, painting his kitchen wall like a blackboard covered in chalky aphorisms and random notes. One line reads, “My assignment is done.”

Artists clockwise from top right: Jessi Zazu, Robert Ellis Orrall, Bongang, Amanda Leadman, Dyl Moss, Harry Underwood, Alison Rhea, Elizabeth Williams, Ian Bush